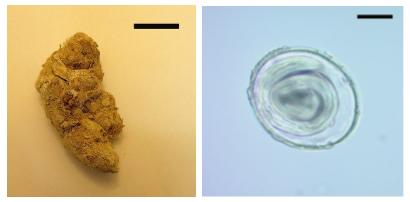

When you’re an 80kg (180lb) apex predator with massive teeth and claws, the world is your litter box—but you might have to wait a few thousand years for someone to come along and clean it up. Archaeologists recently scooped up a dried piece of 16,500-year-old puma feces (called a coprolite) from the floor of the Peñas de las Trampas rock shelter in the mountains of northwest Argentina.

The cold, dry environment helped preserve the material, along with its cargo of a few dozen roundworm eggs, well enough for parasitologist Romina Petrigh and her colleagues to sequence DNA from the eggs. The result is the oldest DNA ever recovered from feces and the oldest parasite DNA ever sequenced.

Big cats and tiny worms

Mitochondrial DNA from the coprolite itself revealed what had left the evidence behind: a puma, the largest member of the family Felidae, which also includes domestic cats. The dried-up calling card showed that Ice Age pumas shared the southernmost reaches of South America with giant ground sloths, now-extinct American horses, and the relatives of modern alpacas and llamas. It also offers a sample of the less-charismatic part of the ecosystem: the parasites that infected the local megafauna. The combination is a snapshot of the complex, untouched world people first walked into around 15,000 years ago (as far as we know based on current evidence; the human settlement timeline is regularly revised as new sites turn up).

The 64 tiny roundworm eggs mixed in with the remains of the Pleistocene puma’s last meal can tell us something about how parasites and their hosts have co-evolved over the last few thousand years. The roundworm Toxascaris leonina lives most of its life attached to the intestinal lining of carnivores like cats, dogs, and foxes, where it can cause diarrhea, vomiting, and other unpleasant digestive symptoms. Animals pick up the 7-10cm (3-4in.) passengers when they eat an infected rodent—where larvae sometimes lie in wait for a better host—or swallow a bit of egg-laden feces (anyone with a dog and a litterbox in the same house knows that these things happen).

Although the new find shows that T. leonina is an ancient pest, the roundworm still infects modern pets and wild carnivores pretty regularly. It’s so common in domestic cats and dogs that, until recently, scientists thought domestic carnivores had originally spread the parasite to their wild neighbors in the first place. But if pumas in Argentina had intestines full of T. leonina before humans and their domesticated dogs made it so far south, it can’t have been domestic pets’ fault.

“The common interpretation is that presence of T. leonina in American wild carnivores today is a consequence of their contact with domestic dogs or cats,” Petrigh told Ars, “but that should no longer be assumed as the only possible explanation.”

Think of them as smelly time capsules

When you look at the image above, you probably only see a dried-up chunk of cat poop (sorry, not sorry). Biologists like Petrigh and her colleagues see a reservoir of information about ancient ecology and the long, complex evolutionary history of parasites and their hosts. Archaeologists and biologists have studied parasite eggs from human and animal coprolites, from ancient latrines, in the soil of archaeological graves, and even from mummified peoples’ digestive tracts.

To better understand the ecosystem of ancient South America—especially which parasites the first human explorers might have encountered—Petrigh and her colleagues are hoping for similar finds from the area. “Our goal is to compare ancient DNA sequences of T. leonina eggs found in other archaeological sites from Argentina,” Petrigh told Ars. The team also has more coprolites from the Peñas de las Trampas rock shelter to study, as well—and a few of them may turn out to be from humans.

Parasitology, 2019. DOI: 10.1017/S0031182019000787 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1559011