11 min read

For every successful company, hundreds fail and are lost to history. But it’s not always clear who will win and who will lose.

Even some of today’s top companies almost flopped entirely, whether from financial problems, messy lawsuits, or baffled consumers. These companies were so disruptive that competitors, investors, and even the general public doubted their very need to exist.

The podcast Pessimists Archive chronicles why people once thought new inventions like forks, teddy bears, and even mirrors were a terrible idea. And here are six disruptive game-changing companies that once looked destined to fail.

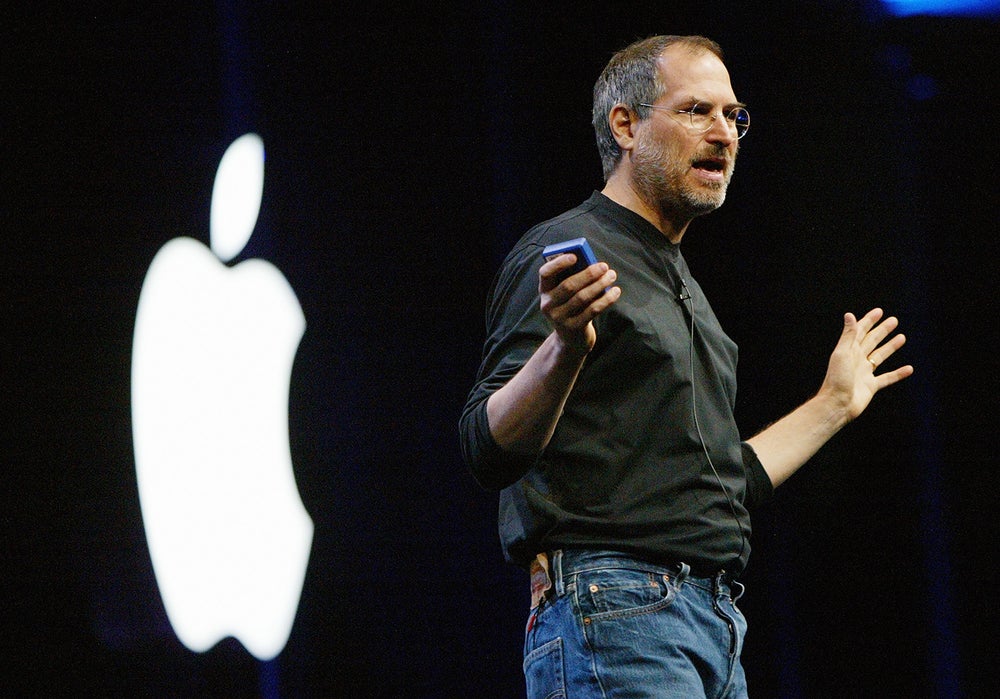

Image Credit: Justin Sullivan | Getty Images

1. Apple

In 1997, things looked bleak for Apple. Since founder Steve Jobs’ 1985 ousting, the company lacked strategic direction. Microsoft and IBM were selling more personal computers. The company had just posted a $1 billion loss on $7 billion in revenue and laid off a third of the workforce. The unwieldy product line spanned dozens of items, including a bunch of printers and servers. The company was just 90 days from bankruptcy.

Apple’s operating system was failing, so the company’s leaders acquired Jobs’ new software company, NeXT. Within a few months, Jobs was in charge again.

He swiftly cut 70% of the product line. At the 1997 Macworld Expo, he stunned the tech world by announcing an alliance with a major competitor: Microsoft would invest $150 million in Apple, and Microsoft Office would be supported on the Mac.

Jobs was booed. But he was also cheered. As he explained, “If we want to move forward and see Apple healthy and prospering again, we have to let go of a few things here. We have to let go of this notion that for Apple to win, Microsoft has to lose.”

Within a year, Apple turned a $1 billion loss into a $300 million profit. Jobs launched the “Think Different” campaign and the iMac G3, the candy-colored, all-in-one desktop. The iPod followed in 2001, then the iPhone in 2007.

By 2018, Apple’s ecosystem of products, software, and die-hard fans made it the first publicly traded American company with a trillion-dollar valuation.

Image Credit: Ethan Miller | Getty Images

2. Google

AltaVista. Lycos. Excite. LookSmart. Dogpile. WebCrawler. AskJeeves.

In the mid to late 1990s, search engines were a dime a dozen. Did anyone really need another one?

A Stanford student named Larry Page thought so. He realized that those early search engines had no way of indicating which sites were more trusted or relevant. While academic papers count citations to show their relevance, the web lacked something similar.

Page named his new project BackRub, after websites’ backlinks. Another Stanford student, Sergey Brin, joined on to help create an algorithm that used these backlinks to rank sites’ popularity. Sites with lots of links merited more “authority” and ranked higher in search results.

The pair was happy to find that BackRub’s results were more relevant. Plus, unlike other search engines struggling to keep up with the web’s growth, BackRub’s algorithm got better as the web got bigger. They (wisely) renamed their product — ditching BackRun in favor of a new name, Google — and went live on the Stanford website in August 1996.

For a few years, Google enjoyed steady growth and investment and began maturing into a real company. But it hardly seemed like a game-changer. Yahoo was the dominant search engine of the time, and even tried to acquire Google for $3 billion in 2002. When Google went public in 2004, its unconventional “Dutch auction” IPO was underwhelming. People just weren’t sure that a search engine could ever make real money.

Google proved people wrong — though not without its own failures. Remember Google Wave, Google Buzz, Google Video, Google Radio Ads, and dozens of others? Still, Google invented an industry, a marketplace, and a verb. Last year, its parent company Alphabet Inc booked $161.9 billion in revenue.

Image Credit: FREDERIC J. BROWN | Getty Images

3. Tesla

Who thought Tesla would fail? Well, start with Tesla founder Elon Musk.

“I didn’t really think Tesla would be successful,” Musk once said. “I thought we would most likely fail. But I thought that we at least could address the false perception that people have that an electric car had to be ugly and slow and boring like a golf cart.”

But Tesla didn’t exactly set out to compete with existing cars. It has long begged the question: is it a software company, a car company, or something else entirely?

That disruptive thinking has caused plenty of problems. In 2008, the company faced serious quality issues and narrowly escaped bankruptcy. Missed deadlines scared off potential customers. Last year’s Cybertruck didn’t help. Nor did Musk’s tweets that ran afoul of the Securities and Exchange Commission. And 41 executives quit between January and September of 2018.

Tesla has its share of doubters and haters (including many burned short sellers) who use the $TSLAQ hashtag to celebrate negative news. (A “Q” on the end of a ticker symbol indicates the company has gone bankrupt.)

But Tesla continues to thrive — even as the company named “scrutiny of critics” as a risk to its business in its 2019 annual report. Critics may remain, but the company now has many high-profile admirers. Volkswagen CEO Herbert Diess said last year, “Tesla is not niche… We have a lot of respect for Tesla. It’s a competitor we take very seriously.”

Today, as battery prices drop and Tesla finally begins to master economies of scale, things are looking up. Customers are loyal — much like Apple customers, in fact. While COVID torpedoed demand for cars, Tesla’s Q3-20 sales were up 22% (over Q3-19) while the industry as a whole was down 9%. And as of mid-October 2020, Tesla’s stock value is up by 400% for the year, on target to deliver 500,000 vehicles for the year.

Image Credit: SOPA Images | Getty Images

4. Airbnb

In 2008, a pair of broke San Francisco roommates, Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, built a website to house conference attendees who were shut out of overbooked hotels. They found three people willing to pay $80 per night for an air mattress and breakfast. Realizing they were on to something, they recruited a friend, Nathan Blecharczyk, to help house attendees of the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver. The site drew hundreds of listings but didn’t make any money.

Fledgling Airbnb was nearly bankrupt, earning just $200 a week. Desperate, the founders maxed out their credit cards and applied their design talents to “limited edition” cereal boxes — Obama-O’s and Cap’n McCain’s — that raised $30,000.

Meanwhile, the trio noticed something: their hosts’ early-era camera phones took grainy, bleak photos of their listings. The team scraped together money to fly to New York City and visit 40 of their hosts, taking high-resolution photos and helping improve listings. Those better profiles doubled Airbnb revenue to $400 per week — the most growth they had seen in eight months.

More importantly, they spent time talking to those hosts.

The founders realized that Airbnb was capturing a unique market. Unlike chain hotel guests who craved consistency, Airbnb guests wanted authentic experiences, often in residential areas away from commercial centers. They liked bungalows and treehouses, urban lofts and houseboats. They wanted a local’s suggestions for where to relax or explore. The founders rejiggered their site and processes to meet their customers’ needs.

Airbnb reached profitability in 2016, even as local governments began passing ordinances to collect occupancy taxes or outright ban the service. And by late 2019, Airbnb was valued at $31 billion.

The pandemic forced Airbnb to raise $1 billion and cut 25% of the workforce as bookings evaporated. The company’s valuation sank to $18 billion in April.

But the company pivoted, playing up its advantages over hotels: kitchens, no stranger-filled lobbies, and the ability to “get away without going far,” which resonates with vacationers wary of air travel.

And while revenue is down, Airbnb reportedly plans to take the company public later this year.

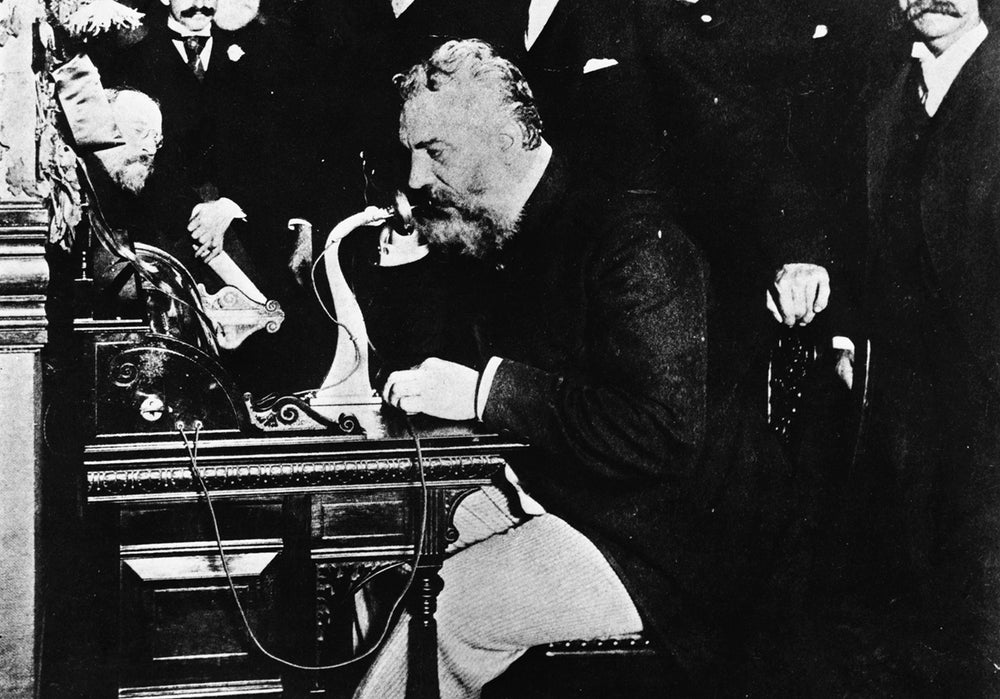

Image Credit: Hulton Deutsch | Getty Images

5. Bell Telephone Company

“That’s an amazing invention, but who would ever want to use one?” President Rutherford B. Hayes asked when he first saw a telephone in 1876.

After all, it was the height of the telegram era. That year, Western Union sent nearly 20 million messages from 7,000 offices across 185,000 miles of wire.

Despite Hayes’ hesitation, Alexander Graham Bell was among many inventors clamoring for the first telephone-related patents. Bell got there first — and immediately faced costly legal battles. Even though no one was quite sure whether the telephone could supplant the telegraph, there sure was a lot of fighting over the patents.

As Bell faced financial ruin from all the lawsuits, he approached Western Union with a proposal: he would sell them his patent rights for $100,000.

Western Union was uninterested, responding: “Why would any person want to use this ‘toy’ when he or she can send a messenger to the telegraph office and a message can then be sent to any large city in the country?”

Despite turning down Bell, Western Union soon partnered with the man who filed his patent just hours after Bell’s.

More lawsuits ensued, and Bell’s father-in-law formed the Bell Telephone Company to protect the patents. The two sides settled in 1879 when Western Union agreed to drop out of the telephone business entirely.

The Bell Company — minus Alexander, who had moved on to other things — faced 587 court battles until the patents expired in 1894. And then competition exploded.

The company retaliated by acquiring many of its 3,000+ competitors, including Western Union (who had been unable to resist the telephone). Decades of anti-trust lawsuits followed. However, the sheer cost of stringing cable allowed AT&T (originally a Bell company that later absorbed its parent) to create a natural monopoly that persisted until the feds broke up “Ma Bell” in 1982.

Naturally, the cycle repeated: the “Baby Bells” began acquiring each other until the largest, SBC, bought AT&T in 2005 and re-claimed the historic name. Today, AT&T comprises ten of the original 22 Baby Bells — and you may very well be using one of its services to read this article.

Image Credit: Alfred Eisenstaedt | Getty Images

6. Disney

Walt Disney wasn’t always a success. In fact, in his early 20s, he was fired by a Missouri newspaper for “not being creative enough.”

Undeterred, Walt and his brother Roy founded Laugh-O-Gram Studio in 1921. It quickly went bankrupt.

With just $40 to his name, Walt left Kansas City for Hollywood. After a (failed) acting stint, Walt invited Roy to help found the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio in 1923. At first, Walt created shorts featuring Oswald the Lucky Rabbit — until his producer stole his team of animators, his rights, and his revenue. Walt’s next character, Mickey Mouse, wasn’t nearly as popular as Oswald, and Walt was rejected by more than 300 bankers before one agreed to fund his work. Though the Mickey shorts were popular, the business struggled and Walt suffered a nervous breakdown.

In 1934, Walt wanted to try a feature-length film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. His brother and wife thought it was a terrible idea, especially when he needed to mortgage the family home to finance the project. The industry called it “Disney’s folly” as the cost swelled to nearly $1.5 million, six times his original budget.

Snow White became what was then the highest-grossing film of all time, earning over $8 million during its original release. But Disney’s next three movies, (Pinocchio, Fantasia, and Bambi) all flopped. His animators went on strike. Debt mounted.

However, television presented a new opportunity. The Mickey Mouse Club and Davy Crockett brought in enough revenue to finance Disneyland’s 1955 launch. From there, the brand only grew.

Today, Disney is an entertainment behemoth, with theme parks, a lifestyle, even its own town. And Walt Disney won 22 Academy Awards from 59 total nominations — the most an individual has ever won.

Want more stories of disruptions that almost didn’t make it? From coffee and comic books to the humble fork, check out the Pessimists Archive. Or, listen to this episode about the fork here:

https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/360532