April 2, 2020

John Boardley

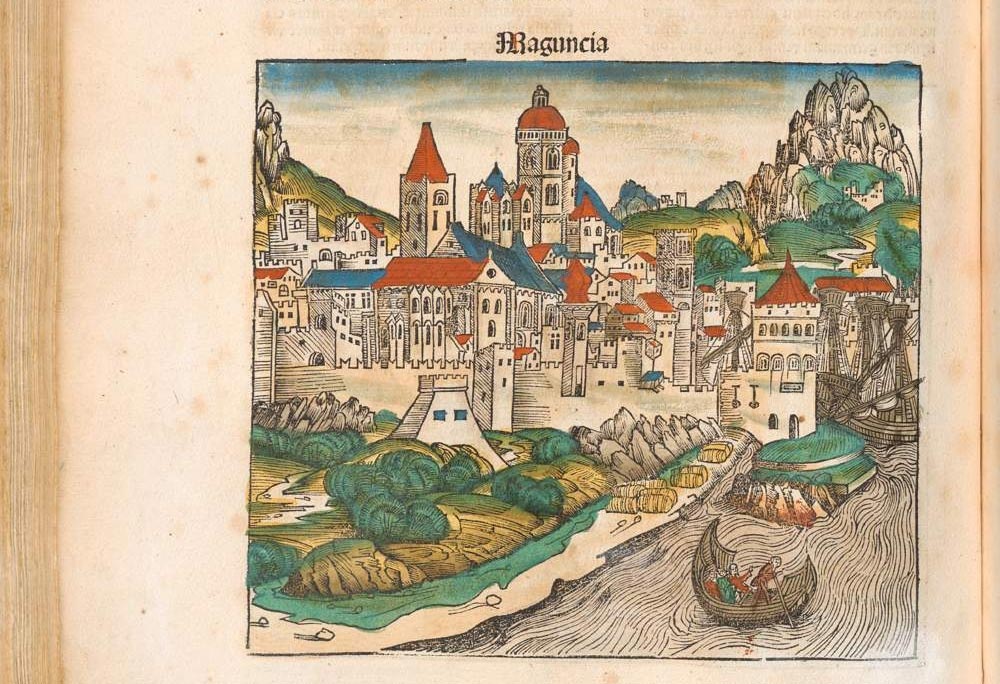

We don’t know for sure what prompted Hans Gensfleisch to leave his hometown of Mainz in western Germany for Strasbourg in the south but leave he did, probably in the early 1430s. Founded in the first century BC by the Romans, under emperor Augustus, Mainz had for a time, after the construction of its cathedral in the tenth century, flourished. However, by the 1430s, the city’s fortunes had taken a turn for the worse and soon was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Clearly, Mainz was not a place conducive to Hans’s entrepreneurial ambitions and he, along with many others, abandoned the city in search of improved prospects. Even a half-dozen years or so after Hans had left the city, and a sign of just how desperate its plight had become, Mainz, in an attempt to stem the tide of economic mass migration, promised potential settlers the generous inducement of a ten-year tax break.

Although Hans didn’t leave behind a diary, I think it’s safe to assume that the dire economic situation in Mainz was a significant factor in his decision to leave. That he chose Strasbourg over, say, the much closer Frankfurt or even one of Germany’s major trade centers, like Cologne, Augsburg or Nuremberg, likely had something to do with the fact that his mother’s family lived in Strasbourg. Also, from the fourteenth century, Strasbourg had established itself as an important trading center standing on good trade routes east to France, to Basel in the South, and northeast to the Low Countries and beyond. Moreover, Strasbourg was home to four religious houses, nine parishes, twenty monasteries and eleven convents, with the religious houses and monasteries homes to considerable libraries, a factor that might well have been connected to the work he would pursue in the coming decade.

As Hans headed south along the meandering Rhine river he was flanked to the west by the Vosges mountains; to the east, the lush green tones and densely forested hills of the Black Forest. His journey took him past the medieval Trifels Castle, above the Queich valley, famed for Richard the Lionheart, who was imprisoned there for three weeks at the close of the twelfth century — one of several locations he was held during his 14-month captivity at the hands of Duke Leopold of Austria.

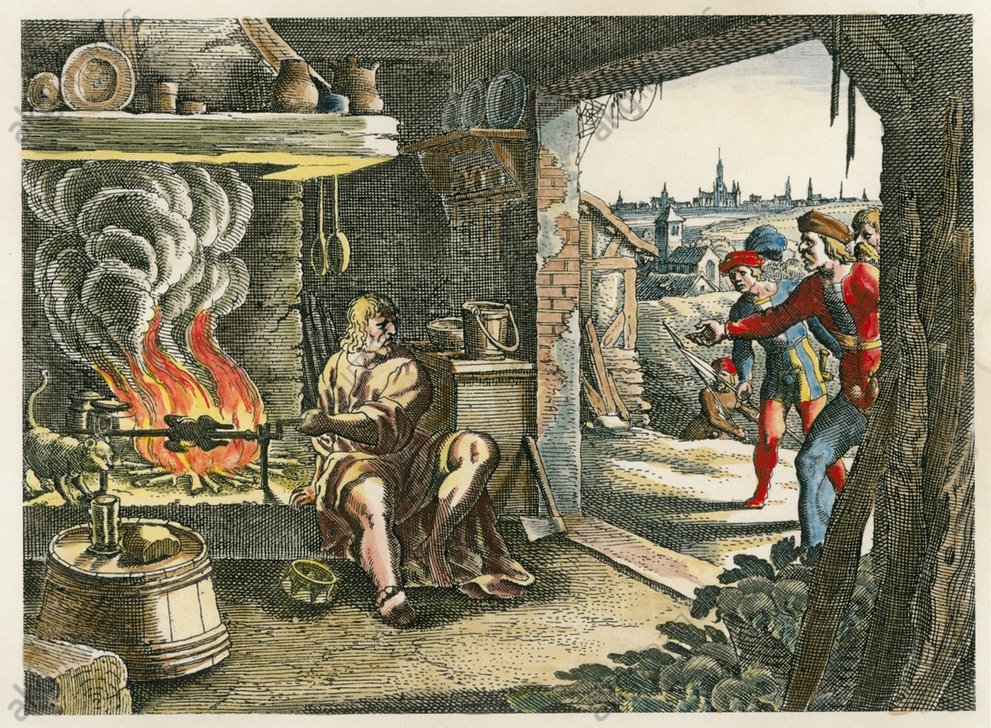

According to one of several accounts of his capture, Richard had been shipwrecked on his return from the Third Crusade, where he had fallen out with his former ally, Leopold. Forced to continue his journey back home to England, overland through Austria, Richard was apprehended at a Viennese tavern or, if we are to believe the King of France’s account, a domus despecta or a house of ill repute. According to another contemporary chronicler, Richard, disguised as a pilgrim, had sought refuge in the kitchen where, to further blend in and appear as thoroughly plebeian as possible, he turned the spit with his own hand. By some reports, he was given away by his expensive ring. News was relayed to Leopold and Richard was promptly taken prisoner.

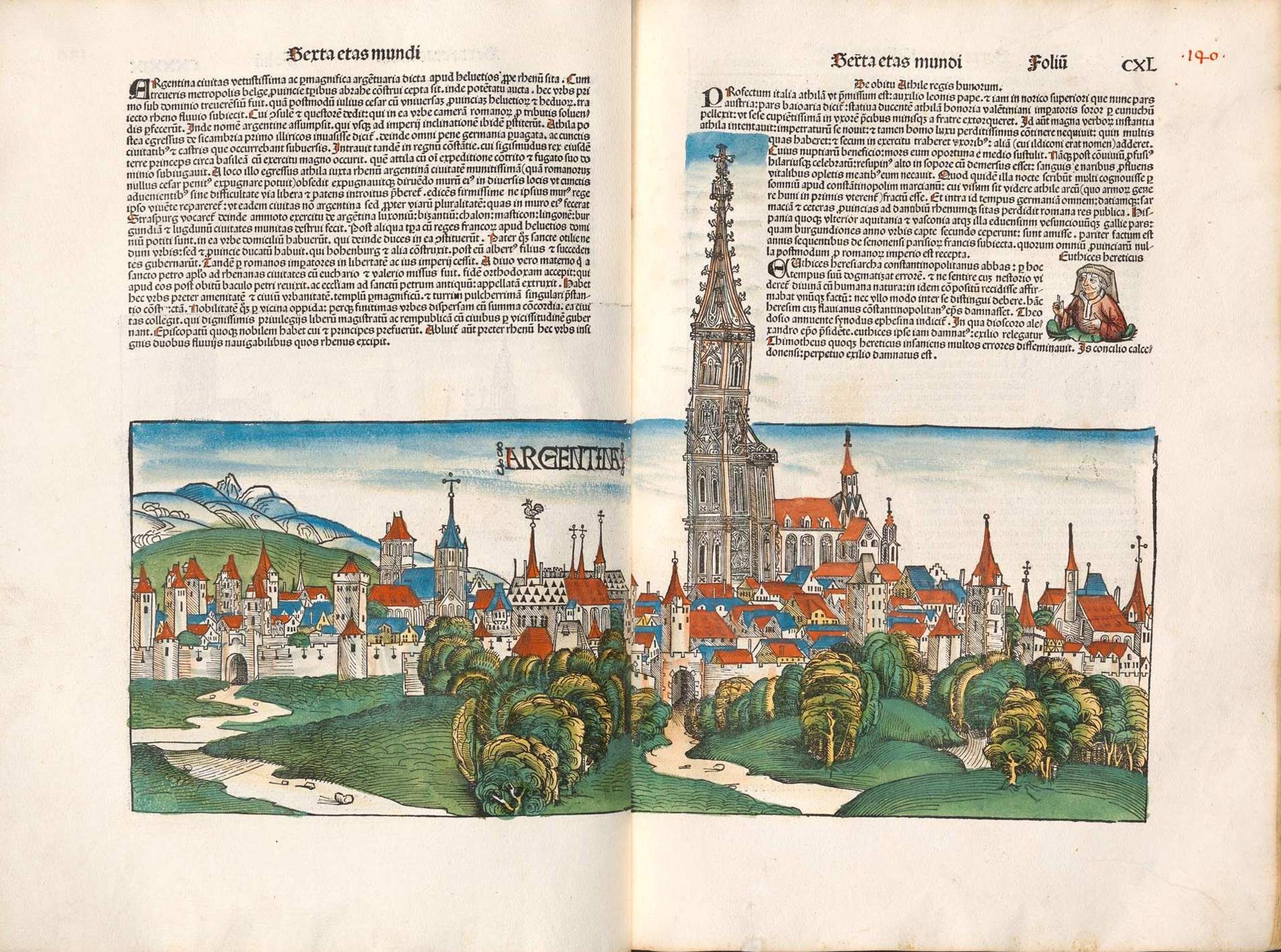

In the intervening two centuries, the landscape had changed little. On horseback, the route would have taken Hans the best part of a week. No doubt he was relieved when, perhaps still a day’s ride distant, the silhouette of Strasbourg Cathedral’s St. Catherine Chapel materialized on the horizon. Perhaps, as he approached closer still, he could make out the scaffolding hugging the as yet unfinished facades of the Cathedral spire. Four hundred years later, Victor Hugo likened the front of the Church to a ‘clever poem‘ and called its spire ‘a gigantic and delicate marvel.’ In the subsequent century, Strasbourg, owing to its association with the Reformation, would go on to become one of Germany’s foremost centers of printing after Cologne and Nuremberg.

Perhaps Hans had witnessed the completion of the Cathedral’s north tower. Begun in 1419 and completed in 1439, it dominated the low-rise Alsatian cityscape of the traditional black and white timber-framed buildings, or Fachwerkhäuser. As the last of the Cathedral’s distinctively pink-colored stones, hewn from the nearby Vosges, was set in place, an enormous metal cross was hoisted 142 meters into the summer sky, secured atop the finial and, in the process, consummating the tallest building in northern Europe. While hundreds of journeymen, masons, stone-cutters, glass-makers, roofers, carpenters and blacksmiths had filled the city to complete construction of the Cathedral, Hans Gensfleisch, better known as Johannes Gutenberg, had been busily experimenting in the secrecy of his Strasbourg workshop.

Magic Mirrors, Sacred Souvenirs

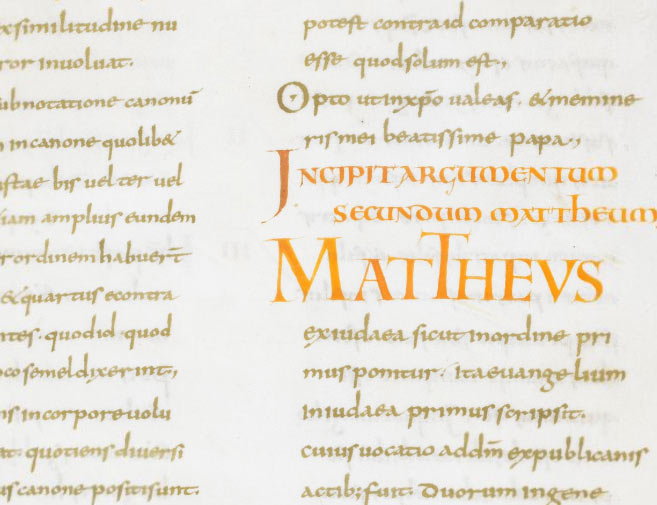

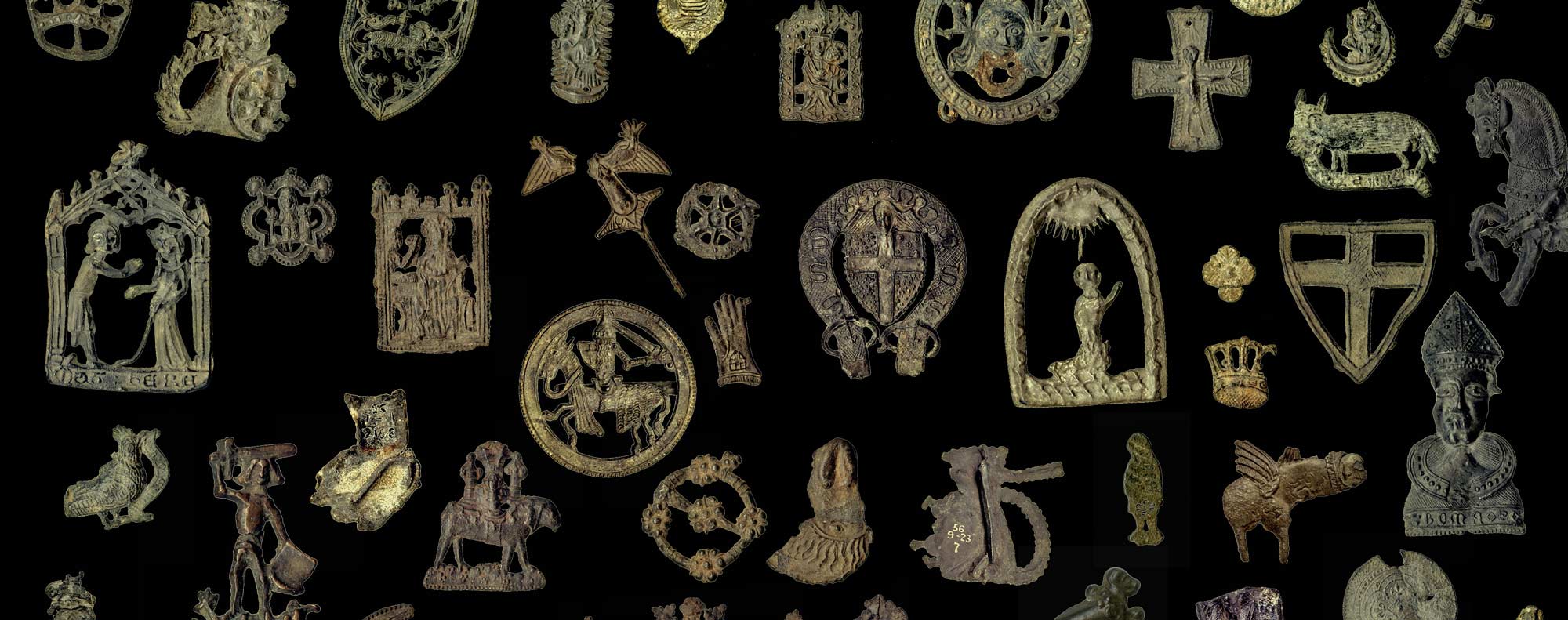

What we know of Gutenberg during his stay in Strasbourg is limited to a handful of tax records and lawsuits. From the latter, we learn that he had partnered with three men to make pilgrim badges for the upcoming Aachen pilgrimage. Now Germany’s westernmost city, on the border with Belgium and the Netherlands, Aachen is best known for its association with Charlemagne (747–814). As capital of the Carolingian Renaissance During the late eighth and ninth centuries, Aachen was also a notable center of manuscript production and, according to one estimate, its schools and scriptoria, turned out as many as 50,000 manuscripts in the ninth century alone. The richly illuminated Aachen Gospels and the Harley Golden Gospels, products of Charlemagne’s Court School, are among the most exquisite illuminated manuscripts of the time. They were penned in a newly invented script, the Carolingian minuscule. Six hundred years later this script would be rediscovered by the founders of Italian humanism, and used as a model for another script called humanist minuscule. That in turn would, thanks in part to an accident of mistaken provenance, serve as the model for the modern lowercase Latin alphabet and subsequent roman fonts — letterforms still in use today.

Aachen Cathedral, built by Charlemagne at the end of the eighth century, had long been one of Europe’s most important centers of pilgrimage. The Christian faithful came from all over Europe to get a glimpse of its sacred relics, including Jesus’ swaddling clothes, the loincloth worn at his crucifixion, and the cloth used to wrap the severed head of John the Baptist.

Anyone who has read Chaucer’s bawdy and brilliant The Canterbury Tales (c. 1400), will be familiar with the manifold motives of medieval pilgrims. In addition to the most obvious and compelling penitential motivations, a pilgrimage was for many the only opportunity to travel — an expression of medieval wanderlust in an age that was otherwise intensely parochial. Pilgrim badges also feature in the The Canterbury Tales, with the fraudulent and greedy Pardoner, a seller of indulgences for the Church, making a little money on the side by selling chicken bones and rusty baubles passed off as holy relics. He also steals pilgrim badges from Canterbury Cathedral, for resale.

Unholy Pilgrims, Holy Vulvae & Pious Phalluses

The bad behavior of pilgrims was not only addressed in works of fiction. Thomas à Kempis, writing in the early fifteenth century, was similarly crtical of pilgims, suggesting that, driven by curiosity and sight-seeing, their peregrinations affected no appreciable change in their lives. In the early sixteenth century, Erasmus cautioned pilgrims to stay at home, rather than gallivant around the continent in a kind of medieval road-trip, leaving their wives and children behind, only to return weeks or months later, their heads ‘full of superstition’. In his Colloquies (1518), he condemns contemporary religions practices, including the veneration of saints and relics, and again takes aim at pilgrims, ruthlessly parodying them in a conversation between the fictional Menedemus and Ogygius, whose names mean ‘stay at home’ and ‘simple-minded’.

Just as Erasmus had mocked and parodied insincere and gullible pilgrims in writing, so others did the same by wearing parody pilgrim badges. Unearthed right alongside thousands of religious badges are many erotic examples. There’s a good chance that these profane badges were sold right alongside the regular kind, depicting shrines and saints, or Christ and the Virgin Mary. In fact, the mass production and sale of pilgrim badges was part of a larger ‘industry’ that serviced pilgrims, including, inns, brothels and souvenir shops. Some of the profane or secular badges parodied pilgrims’ tokenism or false piety, made fun of their ulterior motives and sexual appetites; others were probably contemporary Christianized versions of ancient pagan fertility symbols; some might have been worn as a joke.

“When visiting such places [of pilgrimage], men are often moved by curiosity and the urge for sight-seeing, and one seldom hears that any amendment of life results.”

— The Imitation of Christ, Book IV, 1:9, by Thomas à Kempis, c. 1418–27 (translation from Diana Webb, 2001, p. 240)

And, whether those erotic badges were sold openly or discretely, they demonstrate that our medieval ancestors had a sense of humor, even when it came to religion; and that they weren’t particularly squeamish when it came to wearing tin badges depicting flying penises and walking-talking vaginas.

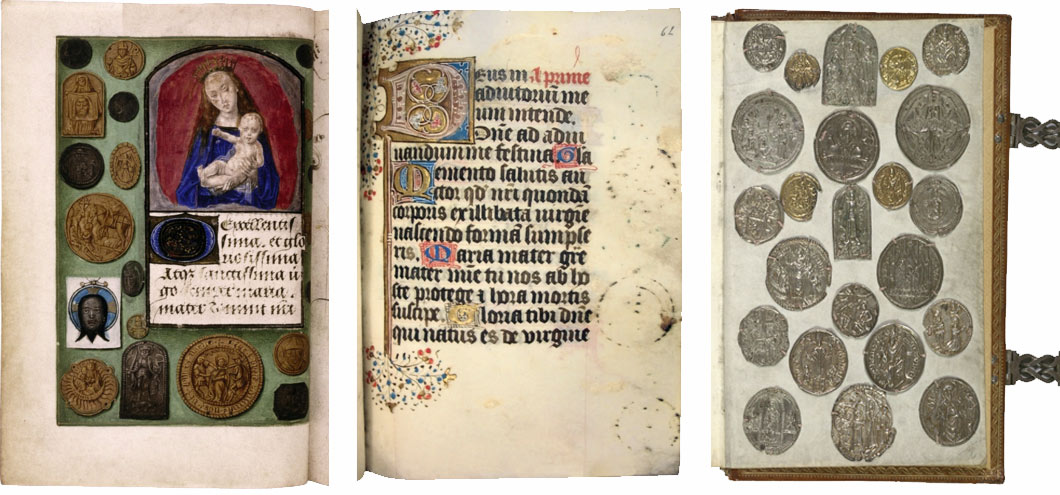

The pilgrim badge, then, served both as a souvenir and a religious symbol or charm. Back home they might be nailed above a doorway for protection, dipped into water to make it holy and healing, or perhaps even tossed into rivers as votive offerings. Sometimes they were even sewn into prayer books, commemorating pilgrimage and serving as objects of private devotion and spiritual contemplation.

Pilgrim badges not only generated significant income for the Church, but served to advertise a whole host of holy sites and relics. One of the Aachen badges, for example, incorporates depictions of Charlemagne and one of Aachen’s principal attractions, a linen gown worn by Mary, a relic gifted to Charlemagne in 799 by the patriarch of Jerusalem. In England, Thomas Becket, the martyred and sainted archbishop of Canterbury, was a very popular figure on English badges.

Back to Gutenberg

Originating in the twelfth century, these badges were at their most popular in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, with millions of them produced in thousands of designs. Gutenberg would have been keenly aware of just how lucrative the sale of pilgrim badges could be. In his day, some pilgrim centers sold hundreds of thousands. What’s more, the badges that Gutenberg and his partners made for the Aachen pilgrimage were of a relatively new design that incorporated an ingeniously practical solution to a growing foot-traffic problem.

As pilgrimages became more popular and their numbers swelled, in some instances, to many tens of thousands, it became increasingly more difficult for pilgrims to approach, let alone touch the relics. And why travel across a country or a continent, if when you arrived you couldn’t touch the very object of your pilgrimage! The ingenious solution was a new badge design, inset with a polished stone, or mirror, which could, even from afar, capture the relics’ reflection or ‘sacred emanations’, transferring some of their miraculous powers to the mirrors themselves — not only did this solve the crowd problem, obviating the need for physical contact with the relics, but the mirrors, now imbued with a holy aura, could be returned home to bring good luck, cures, and divine blessings to anyone who came into contact with them.

From Pilgrim Badges to Print

I think it very likely that it was in Strasbourg that Gutenberg first came up with the idea of printing with pieces of cast metal type. On Christmas Day 1439, Andres Dritzehen, one of Gutenberg’s business partners died. A lawsuit brought by Dritzehen’s two sons shortly thereafter, reveals that Gutenberg and company (Hanns Riffe, Andres Heilmann and Andres Dritzehen) had been involved in a top secret project. Witnesses mention seeing a ‘press’ and ‘form’, plus another mysterious device disassembled into four pieces. Whether the press and form are the printing press and printing forme, we can only speculate. And the enigmatic four-component device that Gutenberg was in such a hurry to have disassembled, lest anyone should fathom its purpose — perhaps it was a prototype mould for casting letters. Hand-moulds for casting type also comprise four main components, so either that device was indeed an early prototype for casting pieces of metal type, or it might have been for casting pilgrim badges. Perhaps in his efforts to devise a method for more easily and rapidly casting pilgrim badges, Gutenberg hit on the idea of casting individual metal letters, arranged and inked to print words and books.

Add to these tantalizing details the fact that one of Gutenberg’s partners, Andres Heilmann, was also the owner of a paper mill, and it would not be unreasonable to surmise that it was indeed Strasbourg that was home to Gutenberg’s earliest experiments with fabricating pieces of metal type. However, if that were the case, then nothing of those earliest Alsatian experiments has survived. However, beyond the speculative joining of dots, what is certain is that by the 1440s Gutenberg’s printing press was in operation in Mainz, printing broadsides and small grammar books or pamphlets.

The video below is a modern-day re-creation of the casting of a (now lead-free) pewter pilgrim badge. The mould is not entirely unlike the hand-mould used for casting pieces of metal type.

And here’s a video of casting metal type in a hand-mould. The alloy used for metal type must be harder and more durable than that used in the casting of pilgrim badges. Therefore, it is made with a little more tin and antimony, thus making it harder and more suitable for many thousands of impressions in a printing press.

Such a hand-mould was used, in much the same form, for 400 years, right up until the invention of automated type casting in the nineteenth century.

Nowadays, badges are worn for similar and different reasons. They reveal political allegiances, club affiliations, remind us to vote, mock dimwitted and dangerous leaders; or are worn as genuine symbols of piety and religious devotion. Whatever the motives or reasons, their distant tin and lead ancestors might well have been crucial to Gutenberg’s invention of cast letters of type, and the subsequent printing revolution that gave us billions of books. ◉

ILT is made possible by the super sponsorship of Positype, and the splendid support of these generous friends & supporters.