Another page of corporate history was written this week when Big Boy, the storied quick-service chain whose double-decker burger preceded the Big Mac, fired Big Boy—or, at least, put him on indefinite hiatus.

The towering mascot will be replaced by a character named Dolly, a blond-haired bobbysoxer trotted out to help promote the brand’s hand-breaded chicken sandwich.

“Dolly has been a lifelong friend of Big Boy, but never the star,” marketing vp Jon Maurer said in a prepared statement. She made her debut on Monday—National Fried Chicken Day—because “the chicken sandwich battle has become a phenomenon … and we plan to win the battle once and for all and with a new star paving the way.”

Big Boy’s departure is the latest in a long line of brand mascots that have been given the stage hook in recent weeks, most all of them decades-old figures conceived in less-enlightened times that, many argue, should have been retired years ago. Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben and the Cream of Wheat chef—all symbols born age-old racial stereotypes that no number of corporate makeovers could quite shake off—are some of the mascots that will soon disappear from store shelves.

In the case of Big Boy, however, the dynamics are less clear.

Big Boy corporate has adamantly denied that the decision has anything to do with the coincidental retirements of other mascots or, indeed, with any social issues at all. Instead, it says that putting Dolly front and center will help lure diners back into restaurants that are just coming out of a protracted lockdown period.

“We felt it was necessary to give folks something new to try in a Big Boy, give them a reason to come to our brand and dine in,” the chain’s director of training, Frank Alessandrini, told NBC affiliate Wood TV in Grand Rapids, Mich. “And we kinda want to continue to show that we’re moving forward. We recognize the times that we’re in. But we want to set ourselves up for the future as well.”

The unanswered question, of course, is whether that future would have been a welcoming place for a mascot that is deliberately pudgy—and lampoons that fact—at a time when body inclusivity has taken its place alongside other forms of social and corporate enlightenment.

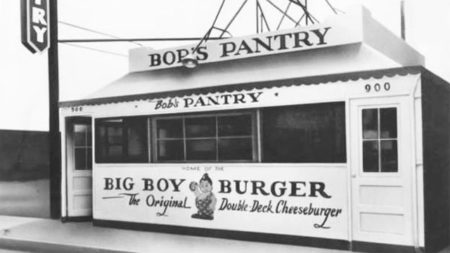

One thing is clear: Big Boy himself was born of a time when nobody thought twice about fat jokes. In 1936, a Glendale, Calif., man named Bob Wian sold his car and used the money to open a 10-stool diner called Bob’s Pantry. When Wian sliced a bun into thirds and served up a double-decker burger, the chain found its signature dish (decades before the 1967 arrival of McDonald’s Big Mac).

As far the mascot, well, he walked in the front door.

Wian’s business partner Glenn Woodruff had a younger brother named Richard, who was tall and heavy for a kid his age. “He was about 6, and rolls of fat protruded where his shirt and pants were designed to meet,” Wian later recalled. “I was so amused by the youngster—jolly, healthy-looking and obviously a lover of good things to eat.”

Wian greeted the youth by yelling, “Hello, big boy!” and the rest took care of itself. An animator named Ben Washam (a regular at the counter, apparently) caricatured Richard with an ample paunch and checkered overalls. By the 1960s, a Venice, Calif., fabricator called International Fiberglass was cranking out oversized mascots that took their places in front of units across the country.

But it’s not as though corporate was unaware that its mascot might have a few downsides. As the years wore on and Americans grew concerned with the health outcomes of a fast-food diet, Big Boy returned to the drawing board and emerged noticeably thinner each time.

https://www.adweek.com/agencies/long-strange-story-big-boy-mascot-lose-job/