Jacob Pustilnik built his first electric bike when he was 17 because he was tired of showing up at school drenched in sweat. Texas is notoriously humid, but Pustilnik only lived a few miles from his school in Houston and was reluctant to abandon his trusty Trek mountain bike. At first, he thought putting a milk crate on the rear rack for his backpack would be enough to eliminate the dreaded back sweat, but it was only a half measure. Eventually he settled on a much more challenging solution: converting his whole bike to run on an electric motor.

“I think I just knew about the idea of an electric bike, but not very much — just that they existed,” he said.

After mulling it over for a couple of months, Pustilnik did what any enterprising teenager would do when they needed some engineering guidance: he went on YouTube. From there, he found someone online willing to sell him a used $800 conversion kit — essentially a kit to convert a traditional bike into a battery-powered one — at a discount. Over the course of a weekend, he transformed his hardtail mountain bike into a throttle-assisted e-bike capable of speeds of up to 20 mph. He would arrive at school soggy no longer.

Conversion kits have been around for years, but have gained popularity as the number of e-bikes sold around the world has exploded. Also, with more how-tos and tutorials available through platforms like YouTube, many people feel like they can gain the skills they need to convert their bikes on the go. There are a variety of types of kits, from wheel kits, to mid-drive motors, to friction or chain kits. But the outcome is generally the same: transforming your human-powered bicycle into one supercharged with electrons.

Building your own e-bike can be more affordable than buying one, especially with most good e-bikes costing between $1,400 and $3,000. The really dirt-cheap kits can be had for around $100 or more. But it’s not without its pitfalls. Inexpensive kits often beget bikes that are lacking in power and performance. Sourcing and building your own battery can be challenging, especially for anyone without basic electrical and soldering skills. And occasionally you can end up spending way more money than you originally intended.

Pustilnik said he was motivated to do it himself partly by saving money — most of the e-bikes he was interested in cost over $2,000 — but also by a sense of freedom. “I like being able to tinker with things,” he said. “And to be able to fix stuff myself as opposed to buying expensive OEM [original equipment manufacturer] parts, or have to wait for someone else to fix it.”

For many DIY e-bike enthusiasts, it’s mostly just a hobby. But there’s also a tacit understanding that if they do an amazing job and really nail that conversion, they can earn some clout on social media, maybe start taking orders from other people — family, friends, perhaps even strangers — who want to buy one of their e-bikes, and suddenly they may find themselves at the helm of a multimillion-dollar e-bike empire.

That’s what happened to Mike Radenbaugh, founder and CEO of Seattle’s Rad Power Bikes. Over the last couple of years, Radenbaugh’s company has risen to the top ranks of e-bike makers in the US thanks to its ability to churn out fast, fun, and affordable products. And it all started very similarly to Jacob Pustilnik’s story, with the need to get to school on time.

Radenbaugh built his first e-bike as a teenager growing up in the rural Northern California town of Garberville, where he and his family lived “sort of off-grid,” he said. He was 16 miles from school, but rather than continue to dump money into an old car that kept breaking down, he opted to build an electric bike using his mountain bike as a foundation.

He spent a lot of time on online forums like Endless Sphere, where e-bike enthusiasts trade tips and talk shop. But he didn’t have a conversion kit to make the transformation easy. Instead he relied on skills he picked up at a local auto body shop to convert a mess of motorcycle parts, moped motors he ordered from Japan, and other odds and ends he had laying around, into a throttle-powered 35-mph e-bike. It was all held together with electrical tape, pipe clamps, bungee cords — and probably a healthy dose of hubris.

“The first one was built just for me,” he said, “and the next ones were built for word-of-mouth sales. I started selling them on Craigslist and I worked my way into the local newspaper with a free advertisement because I think that person running advertising there felt bad trying to charge a 16-year-old.”

And the results were far from perfect. “The parts didn’t fit well, and they didn’t perform well because they were just pulled over off the shelf from other applications,” Radenbaugh recalled. Sensors were getting fried, wires were melting, and the bike was generally falling apart. This reveals a central and uncomfortable truth about DIY e-bikes: a project that is conceived around saving money can sometimes end up costing you way more than if you’d just bought something off-the-shelf.

“You end up spending a lot of money getting to a product that is reliable,” Radenbaugh said, “when you go the DIY route.”

Other e-bike entrepreneurs have discovered this as well. Hong Quan built his first bike in his garage in Palo Alto in the mid-2010s, and from there started his own company, Karmic Bikes. He argues that building your own e-bike as a way to save money can be misguided, especially when you end up with something crappy that defeats the purpose.

“They’ll buy a cheap battery, a cheap motor, and they’ll put it on a cheaper bike,” Quan said. “That’s fine if you want to do that, but you’re not going to get any performance, you’re not going to get any range, you’re not going to get any of the real benefits of having an e-bike.”

For those who aren’t motivated by saving money, the impulse to build their own e-bike seems mostly to stem from a desire to ride faster and farther than most current models allow. YouTube, Reddit, and other forums are bursting with builders bragging about their overpowered e-bikes traveling at motorcycle speeds.

It’s a high wire act, considering the dangers associated with riding a custom-built bike that can match pace with a Ducati. Sure, there are a lot of YouTube views associated with bigger, bolder-looking e-bikes that pack more power than they should. And when you’re building something in your garage, your ability to make the right decisions can be obscured by the amplified voices of online commenters egging you on to build bigger, go faster, and screw the rules.

Until you do it, and immediately regret it. “Never again!” one YouTuber yelped in a video posted in 2017. He could barely be heard above the rushing wind after hitting speeds well in excess of 70 mph on a self-made e-bike he describes as “the most dangerous and unsafe bike ever.”

“Well, it had to be done,” he added. “I wouldn’t be Tony if I did it the usual way!” (Tony, the YouTuber, could not be reached for comment.)

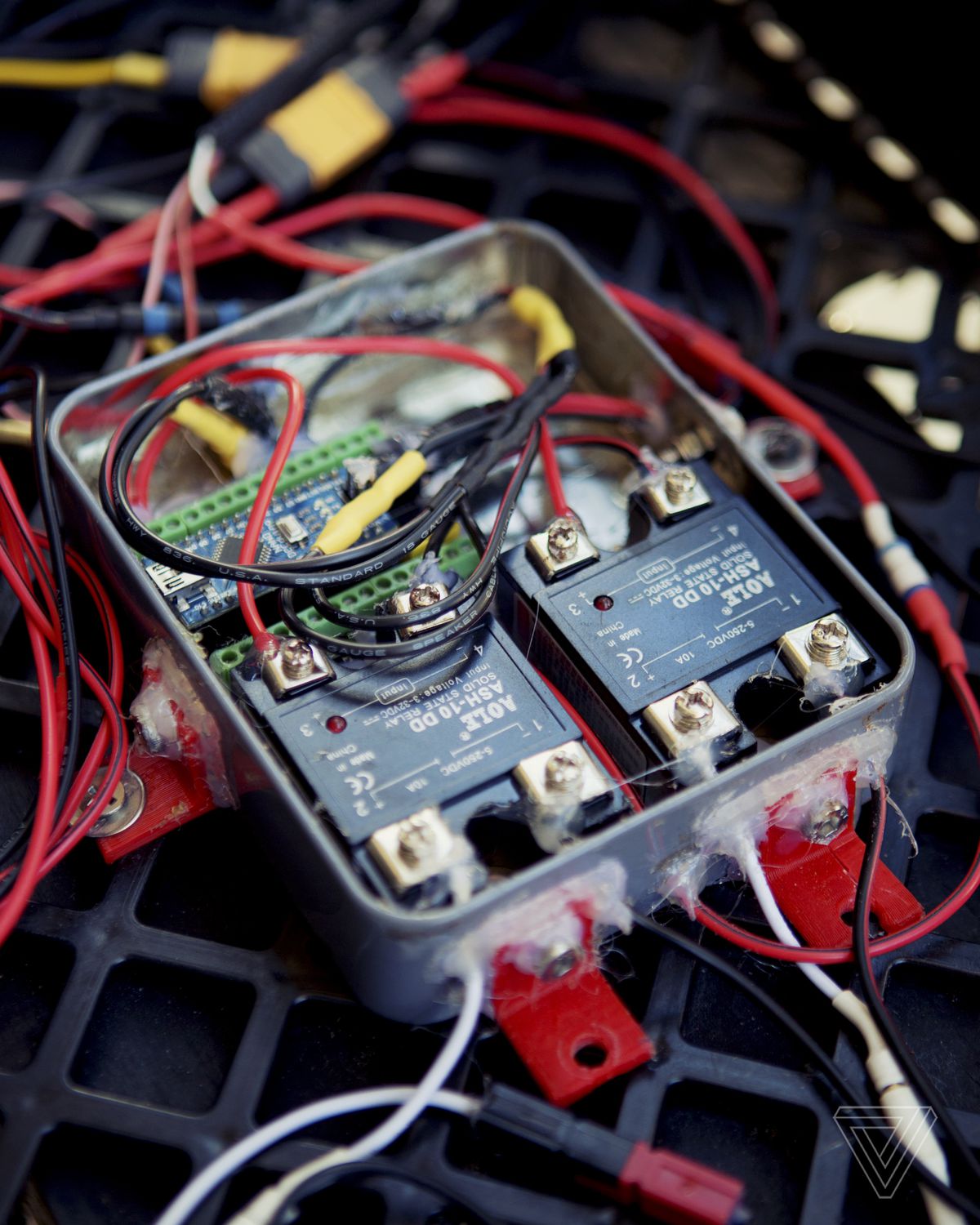

Others are aware of the pitfalls, and are fine with them. Javi Hernandez, a 39-year-old stay-at-home dad who lives in Southern California, has over 19,000 subscribers on YouTube, where he publishes under the handle “Javi’s Boom Tech.” He mostly posts videos about Bluetooth speakers, but lately he’s gotten into building his own e-bikes. His latest, which he calls “Cirkit,” could best be described as an homage to 1970s-era Taco minibikes. The upright handlebars, long banana seat, parallelogram-shaped frame, and Day-Glo green accents are a noticeable contrast to most DIY e-bikes, with their rat’s nest of wires and comically incongruous parts.

Hernandez says he got help from a friend who he describes as “the Rain Man of e-bikes,” who taught him how to build batteries, controllers, and other necessary parts. The batteries, in particular, were difficult to build from scratch. Carefully placing dozens of 18650 lithium-ion battery cells inside a pack, and then wiring, spot welding, and soldering everything together takes a lot of skill, he said.

“That’s the heart and soul of the bike,” Hernandez said. “If the battery can’t output the power that it’s being requested, then it doesn’t matter what you have, as far as controller and motor.”

In the end, he ended up with a 7,000W motor and a 70-volt battery pack capable of 300 continuous amps. In other words, “a beast,” Hernandez said. Compare that to Rad Power Bikes’ cargo bike, the RadWagon, which has a power rating of 750W and a 48-volt battery pack.

“Long story short, we finished the bike and it went from a top speed of 15, 16 miles an hour to about 45 miles per hour,” Hernandez chuckled. “A little rocket.”

Most e-bike companies stick to the US classification system, which caps speed at 28 mph for a Class 3 bike. But Hernandez says he relishes zooming around Los Angeles on his rule-defying Cirkit bike. Recently, he was stopped at a red light when a motorcycle pulled up alongside. The two exchanged glances, and when the light turned green, Hernandez gunned it.

The front wheel, he recalled, just started squealing like crazy and spewing smoke. The biker burst out laughing. “He wasn’t expecting that from this tiny little bike that looks like a kid should be riding it,” Hernandez said.

But Hernandez wasn’t embarrassed. Far from it, actually. “It’s a total blast.”

https://www.theverge.com/22296195/electric-bike-ebike-diy-youtube-conversion-kit-cost