A group of legal experts has delayed a controversial vote about contracts that affects any internet user who’s clicked “Agree” without really reading a platform’s terms of service.

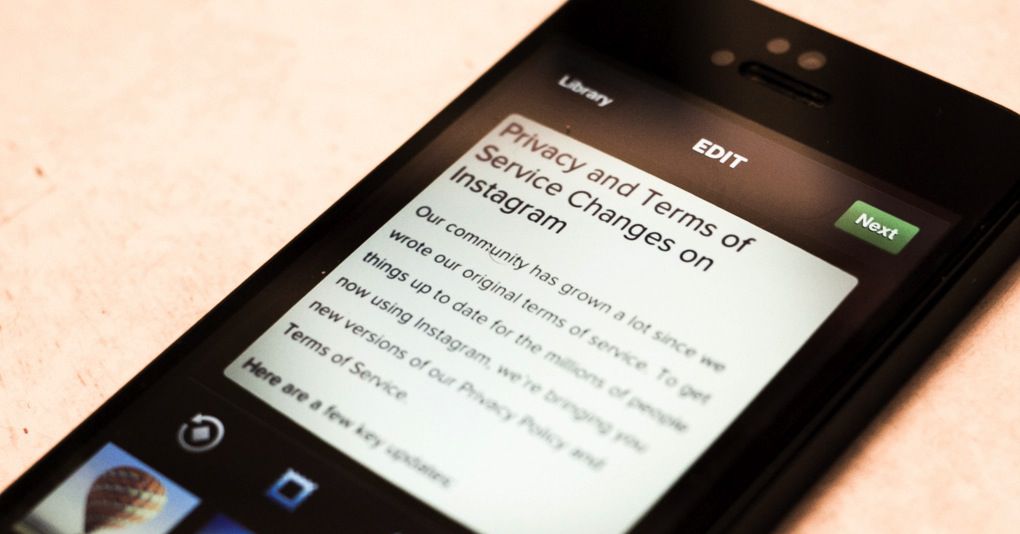

It’s difficult to buy products, use apps, or even go online without accepting the terms of dauntingly long user agreements, which govern everything from how companies use your data to whether you can sue them. People almost universally ignore these contracts, which has created a conundrum for courts: when has a user meaningfully agreed to something, and when is a company taking advantage of their ignorance?

The powerful American Law Institute (ALI) hoped to solve this problem with something called the Restatement of the Law of Consumer Contracts. The proposal has been in the works for years, and the group hoped to pass it at a meeting yesterday. But the proposed restatement galvanized consumer rights advocates into opposition, caused a brief drama when the ALI issued copyright takedown notices to a critic who posted the draft online, and drew fire from two dozen state attorneys general and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), who called the proposal “dangerous.”

A group of lawyers, professors & judges are about to vote on whether to subject consumers to abusive contracts they don’t negotiate and can’t opt out of. This dangerous proposal will shape decisions in courts across the country – it should be voted down. https://t.co/V6aVf2QYoz

— Elizabeth Warren (@SenWarren) May 21, 2019

ALI restatements are supposed to help legal professionals navigate the complex world of court decisions. As the name suggests, they’re meant to authoritatively lay out the way that judges typically rule on a particular issue. That makes them incredibly important reference points. “They get cited all the time by courts. Law students learn the law from these restatements,” explains attorney Deepak Gupta, who attended yesterday’s ALI meeting.

In the case of user agreements, the proposed ALI restatement was to be a “bargain” for consumers and tech companies. It started from a premise that virtually nobody questions: lots of people are agreeing to service agreements — contracts — they almost never read and have little ability to change. From there, it got more controversial. The restatement draft says that as long as there’s “reasonable notice” that such a contract exists, users have effectively consented to follow it. In exchange, users can argue that the contract is unconscionable and shouldn’t be enforced even though they’re legally bound to it. It’s an escape hatch of sorts.

But companies often include forced arbitration clauses in their user agreements, blocking that escape hatch and rendering the “bargain” moot. “I don’t think they were trying to do something that was harmful to consumers,” says Gupta about the restatement’s authors. He still called on ALI members to oppose the restatement, though. “The ‘bargain’ isn’t really a very good bargain for consumers.”

Other critics have been harsher. “The proposed Restatement, if adopted, would drive a dagger through consumers’ rights,” wrote Melvin Eisenberg, professor emeritus at the UC Berkeley School of Law. “It is thoroughly and stridently anti-consumer.” And the 24 state attorneys general called it “an abandonment of important principles of consumer protection in exchange for illusory benefits.”

Warren told The American Prospect that she opposed the decision, and she tweeted her disapproval on the morning of the meeting. “A group of lawyers, professors, and judges are about to vote on whether to subject consumers to abusive contracts they don’t negotiate and can’t opt out of,” Warren wrote. “This dangerous proposal will shape decisions in courts across the country — it should be voted down.”

Businesses won’t necessarily be pleased either. “One of the interesting facets of this project is that there’s actually opposition both from the consumer advocates side and from the business side,” says Cardozo School of Law professor Matthew Seligman, a non-member who also attended the ALI meeting. The latter class includes attorney Alan Kaplinsky, who has staunchly defended arbitration clauses for companies but expressed concerns about the restatement because the unconscionability rule could make contracts too easy to break.

The issue isn’t just the restatement’s language. It’s also the possibility that, in this fast-changing legal and technological landscape, there simply may not be a meaningful consensus about how user agreements should work yet.

That’s the view of Adam Levitin, a Georgetown Law professor who’s been one of the restatement’s most vocal opponents. (He’s come into fairly direct conflict with ALI, which accused him of copyright infringement for copying the restatement draft to a Dropbox account.) Levitin believes there’s “no need” for the project. “When you look at the cases, it’s very useless for giving courts guidance,” he says. “No one’s going to know what’s going to be reasonable or not.”

When the restatement came up at yesterday’s ALI meeting, it wasn’t rejected. But it was immediately mired in debate. Levitin proposed a major amendment to clarify that only “reasonable” contracts were valid, so companies couldn’t slip obviously exploitative clauses into their terms of service. While the amendment didn’t pass, it got a surprising amount of support. The meeting ended without ALI members discussing several sections of the restatement, let alone reaching a final vote.

The ALI could pick the debate up next year, it could rework the language, or it could outright drop the proposal. At the very least, “anyone who was at the meeting should realize that there is no consensus on this project at this point, that the project needs to go back and bake quite a bit longer,” says Levitin. The restatement has already been in the works for several years, and opposition isn’t new. (Warren originally voiced concerns back in 2017.) Now, though, there’s substantially more negative publicity around it.

There’s also a much larger debate over exploitative contracts. Forced arbitration clauses, for instance, have become a hot-button issue at companies like Google where employees say the clauses sweep valid harassment and discrimination cases under the rug. Over the past several months, members of Congress have introduced bipartisan bills to end the practice. “The real fight, the looming fight, is about forced arbitration,” says Gupta.

American consumers are also reckoning with an unprecedented loss of privacy and control. A company that’s ostensibly storing your family photos might be secretly training facial recognition software, a feature that’s vaguely mentioned in the terms of service but that virtually no reasonable user would expect. This restatement would only cover service agreements. But as Levitin points out, that can cover a huge swathe of interactions, and traditional purchases increasingly include subscriptions.

Consumer protection laws certainly aren’t always consumer-friendly, and the ALI’s restatement accurately reflects some verdicts. “Depending on what court you’re in front of, you might get a treatment that looks like that of the draft, [or] you might get a treatment that says ‘We’re not going to hold you to terms that you didn’t reasonably expect,’” says Levitin. But yesterday’s decision (or lack of one) at least means that courts will still have to actively make that call.

https://www.theverge.com/2019/5/22/18634183/consumer-contracts-ali-restatement-law-elizabeth-warren-attorney-general-opposition