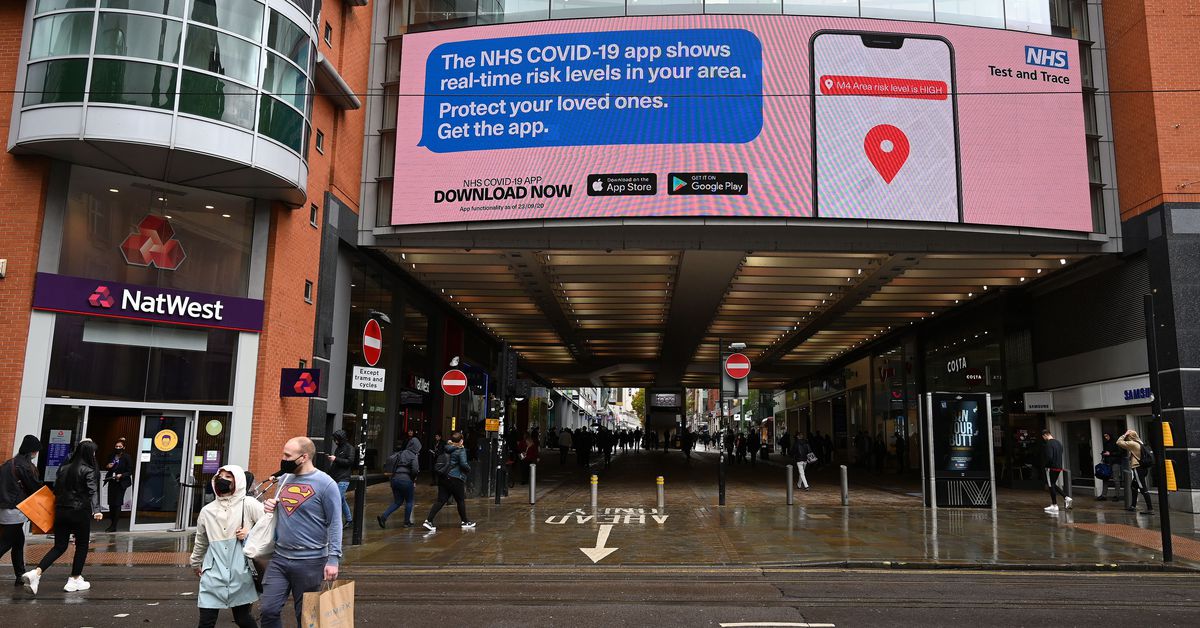

What happens when an app designed to help people navigate the real world doesn’t match up with reality? That’s what happened recently with a National Health Service contact tracing app in England and Wales, which failed to notify many users that they had been exposed to the virus that causes COVID-19.

Like many contact tracing programs, the NHS app keeps track of when a user is close to other people who also downloaded the app. If someone tests positive, the app can send an alert to all their contacts, particularly the ones that they’ve been around the most. The app calculates a person’s risk based on a few factors, including how long they’ve been close to the person who tested positive. If the calculation passes a certain threshold, an alert gets sent, and the person is asked to isolate themselves from others.

The underlying idea is pretty simple. The higher a risk score, the more likely you are to have been exposed to the virus. But then it got more complicated. Before the app was launched, the developers made some adjustments to the algorithm that made each risk assessment more accurate — now, it could take into account how infectious people were at different times. In the new version, interactions outside of the most contagious period only counted towards a fraction of the final risk score, according to reporting by The Guardian. The change automatically lowered almost everyone’s scores. The alert thresholds were supposed to be lowered too, but they weren’t.

As a result, many people who should have taken additional precautions didn’t. The news of the app’s failure broke as COVID-19 cases climbed, and England prepared for a new month-long lockdown — an attempt to stop the resurgent disease spread.

The app has since been fixed, but its threshold issue highlights problems that a lot of apps are struggling with. A very different app had a very similar problem last year. ShakeAlert LA was designed to alert people in Los Angeles to strong incoming earthquakes, but on July 4, 2019, the ground shook, and the app did… nothing. The earthquake fell short of the app’s threshold for sending out an alert, but it was still strong enough to alarm people. After that quake, the app’s creators decided to lower the threshold for an alert — if you feel the earthquake, but the app doesn’t mention it, you might not trust the app even though it’s doing what it’s supposed to be doing.

In the case of both England’s COVID-19 app and ShakeAlert LA, the apps did exactly what they were programmed to do. They just didn’t help the people who were relying on them for vital information about their world.

It’s difficult to quantify risk — most of us know it when we see it, and react accordingly. But for an app, you need something a little more rules-based, which makes quantifying individual risks into something that is usable for programmers and useful for users tricky. Developers for both the NHS app and ShakeAlert LA had to figure out where to put an alert threshold that low enough that people would be informed of danger, but high enough that they wouldn’t be inundated with false alarms.

In both cases, they missed the mark. ShakeAlert LA’s miss was less alarming — they hadn’t guessed that people would still want to know about shaking that was noticeable, but not seriously damaging. That’s a pretty easy fix. In the case of the NHS app though, a misplaced threshold led to thousands of people not being told to quarantine when they should have, potentially contributing to the spread of a disease in a pandemic.

“We haven’t forgotten what this app is for,” the heads of the NHS COVID tracing app wrote in a blog post on October 29. “It’s a tool to help control the spread of the virus, save lives and protect the economy by alerting those who need to, to isolate in order to break the chain of transmission.”

It’s been said before, but technology alone can’t get us out of this pandemic. It is just one tool among the many that we’ll need to complete this job. Even with a perfectly calibrated app, people will still need to keep their distance, wear their masks, and get tested. Robust apps could make living in that reality easier — but only if they can reliably deliver unvarnished reality instead of a false sense of security.

Here’s what else happened this week.

Research

Denmark will cull entire mink population after COVID-19 outbreaks

We’ve learned a few things this week about Denmark. Namely, that it’s the largest producer of mink fur in the world. Also, that it’s planning to cull its entire mink population because it says it has detected a mutated version of the coronavirus in mink populations, and in some human cases. Data on this mutation is still sparse, and is still not clear what effect this mutation might have. (Nicole Wetsman/The Verge)

Additional reading:

New research points to potential link between pollution levels and COVID-19 death risk

A new study published this week found that some areas with higher air pollution also experienced higher rates of death

(Priyanka Runwal/STAT)

Australia has almost eliminated the coronavirus — by putting faith in science

And now for a success story. Not all countries are doing as poorly as the United States at controlling the virus. Here’s how Australia managed to beat back the virus and return to something resembling normalcy.

(A. Odysseus Patrick/The Washington Post)

Development

Will a small, long-shot US company end up producing the best coronavirus vaccine?

Take a deep dive into Novavax, a dark horse in the vaccine race. The company has a promising vaccine candidate, but, as Meredith Wadman notes in Science, “Novavax has focused on making vaccines for more than 20 years but has never brought one to market.”

(Meredith Wadman/Science)

Nasal Spray Prevents Covid Infection in Ferrets, Study Finds

This is cool research, but a few words of caution before you dive in: the study is small, involving just six ferrets. It’s also a preprint, which means it hasn’t been reviewed by other researchers. (Donald G. McNeil Jr./New York Times)

Perspectives

In COVID-wrecked Mexico, one doctor tried humor and home visits

“People are suffering in ways you can’t imagine, and if we bring that fear with us, it only makes them more afraid,” Gustavo Gutiérrez told The New York Times. “The worst part about this damn virus is that we’ve lost our humanity.” Gutiérrez is an emergency room doctor who also makes house calls to COVID-19 patients reluctant to brave the hospital.

(Azam Ahmed/The New York Times)

More than numbers

To the more than 49,169,630 people worldwide who have tested positive, may your road to recovery be smooth.

To the families and friends of the 1,240,344 people who have died worldwide — 235,761 of those in the US — your loved ones are not forgotten.

Stay safe, everyone.

https://www.theverge.com/2020/11/7/21553043/nhs-covid-19-coronavirus-contact-tracing-app-technology-threshold-antivirus