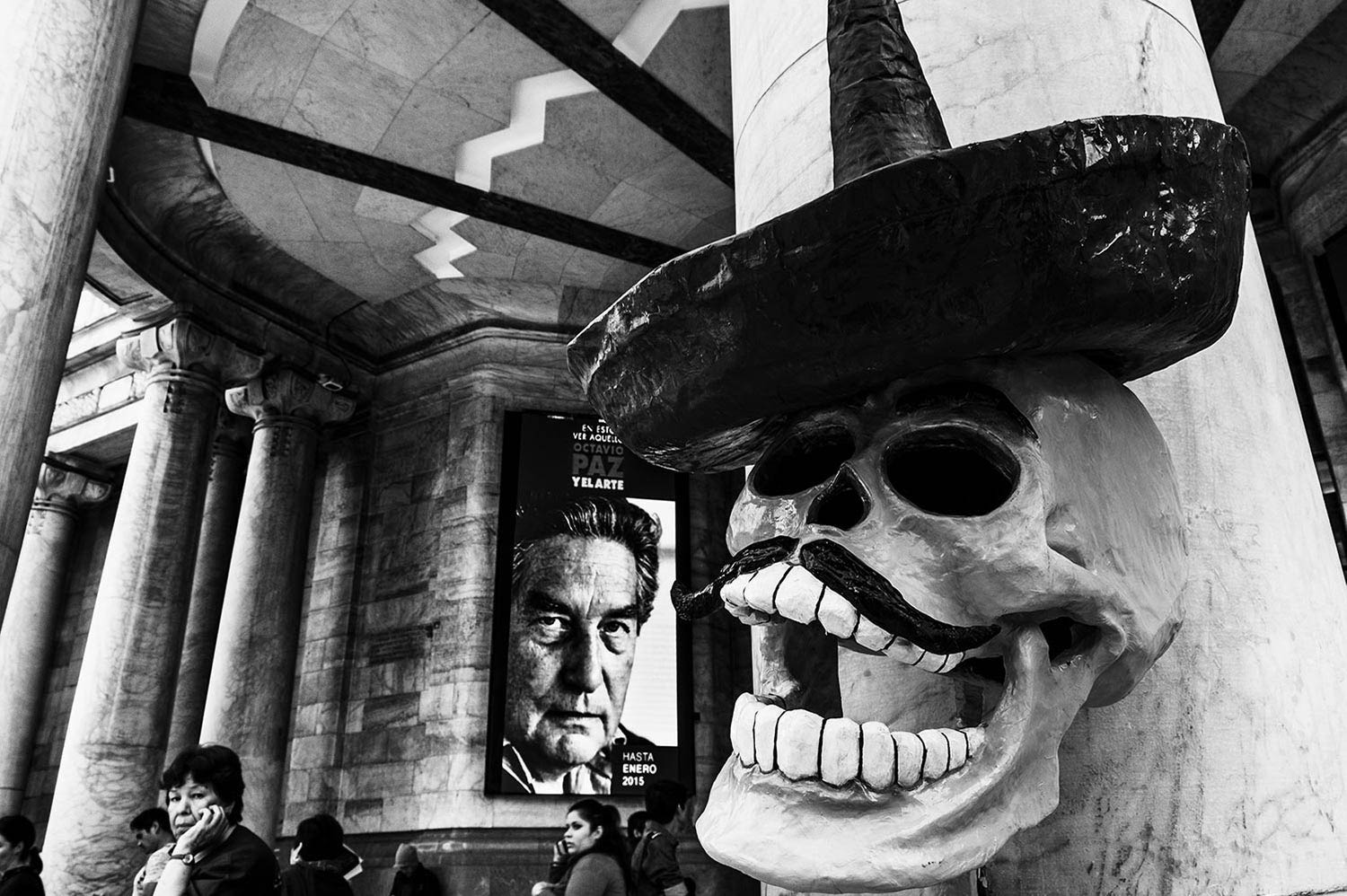

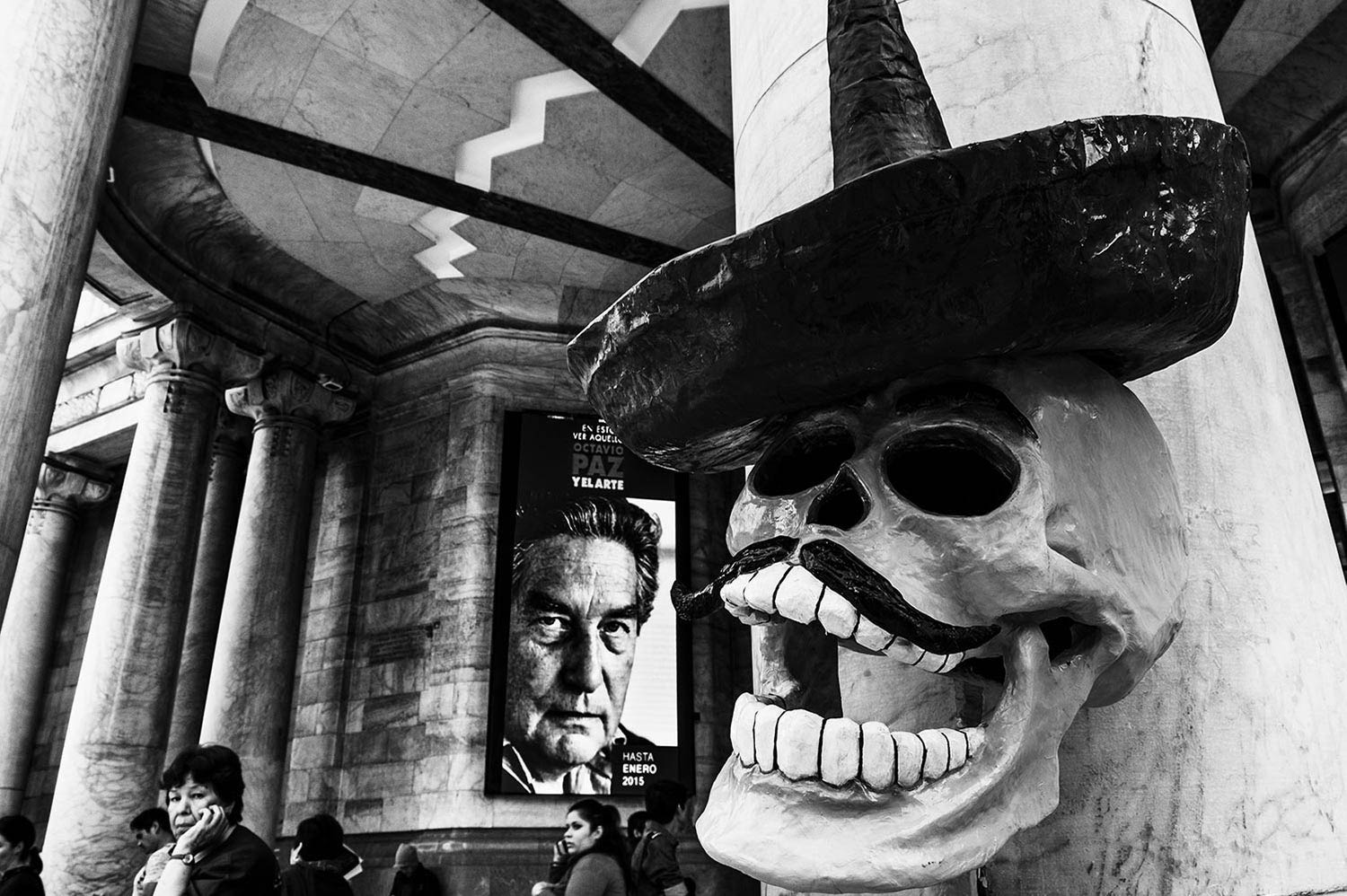

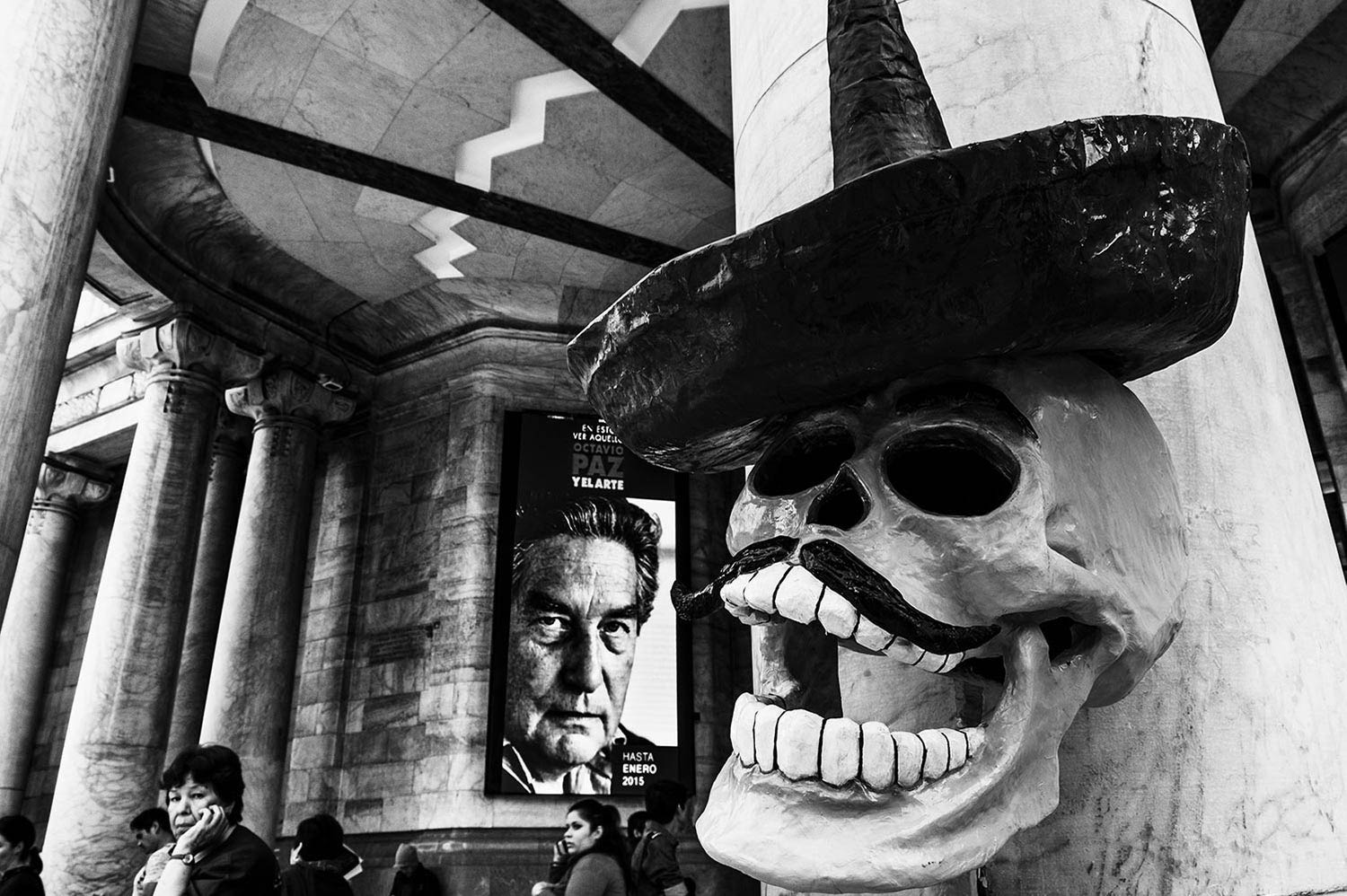

“A cult for life, if it is really deep and complete, bis also a cult till death. The two are inseparable. A civilization that rejects death ends up denying life”.

So wrote Octavio Paz, one of the greatest Mexican intellectuals of the second half of the twentieth century, in The labyrinth of solitude, as an attempt to describe the mysterious and complex philosophy of living in his Country, the so-called mexicanicad, characterized, among other things, by the lack of a separation between life and death.

Without death there would be no life, it is a law of nature. The Día de Muertos that is celebrated today is “a relatively recent hybrid invention, which takes up some pre-Columbian traditions and merges them with the Catholic ones”.

The celebrations range from the night of October 31st to that of November 2nd, but are preceded by a long period of fervent preparations as is customary in Europe for Christmas. Considered “one of the oldest cultural expressions and of greatest importance for the indigenous groups of the country”, the “Day of the Dead” has been declared by UNESCO an “Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity”.

The sadness and sobriety that characterize the day of commemoration of the dead in Europe and North America, in Mexico gives way to a sort of colorful carnival of dances and parades in costume, carpets of orange petals of cempasutichl, the correspondent of our chrysanthemum, concerts of mariachi in front of the tombs in the cemeteries where real banquets are set up that last all night, entertained by rivers of tequila and mezcal that symbolize ideally a festive reunion of the dead with loved ones.

A Every place, public and private, is literally submerged by skulls and skeletons of many varied materials and sizes. The undisputed protagonist is the Catrina of which there is also a male counterpart, El Catrin, a skeletal figure dressed in full dress, complete with a French hat and ostrich feathers, a parody of the ladies of the Mexican upper middle class of the early twentieth century.

This reportage, which shows the astonishment and curiosity of the European look before such an extraordinary and unusual event, attempts, more than to explain, to “stop” – a characteristic of the photographic medium – above all the paradoxical vitality of this picturesque funeral.

The backbone is a series of portraits of people disguised as dead or dressed up as Catrina, faithfully inspired by the image made known by the engravings of José Guadalupe Posada, who he used to remember, in full harmony with the spirit of Dia de Muertos, “a collective and irreverent memento mori”, that rich or poor, powerful or oppressed, we are just walking bones.

In addition to the extraordinary popular participation, this work also aims to tell the different declinations of the festivities, from the center to the suburbs, as in the case of the capital that becomes in those days the scene of political and social claims for the victims of episodes of recent history, so that, paraphrasing Octavio Paz, the memory is a present that never stops passing.

About the author:

Filippo Cristallo was born and lives in Avellino where his passion for photography began. He mainly dedicated himself to reportage, fascinated by the expressive tools and interpretative possibilities that this genre offers.

His works have been published by Witness Journal, Clic-hè’ magazine.

Follow @positive_mag on twitter for the last updates https://www.positive-magazine.com/muertos-filippo-cristallo/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=muertos-filippo-cristallo