December 13, 2020

For more than a thousand years the meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphs was completely lost. For centuries, many assumed that they were magical symbols that might never be understood by mere mortals. In the seventeenth century, the polymath and walking encyclopedia, Athanasius Kircher, came closer than most to understanding how Egyptian hieroglyphs worked, but the real breakthrough only came with the discovery of a 2,200-year-old black basalt slab, now known as the Rosetta Stone, crucial to their eventual decipherment in the 1820s.

The famed Rosetta Stone, rediscovered in 1799, and key to deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. For the story, read The Riddle of the Rosetta.

In my previous article, Emoji b4 Emoji, about those curious hieroglyphic broadsides, we saw how hieroglyphic or ‘hieroglyphick’, as it was often spelled, was used to denote anything remotely exotic, esoteric, or profound. In the two two hand-colored engravings below, the term is used to describe Christian allegories:

1

2

This hieroglyphic literature was all part of a fascination with all things Egyptian which swept through Europe and the United States around the turn of the nineteenth century. Today, we’ll continue with this theme, and take a brief look at another curious product of Egyptomania.

Hieroglyphic What?

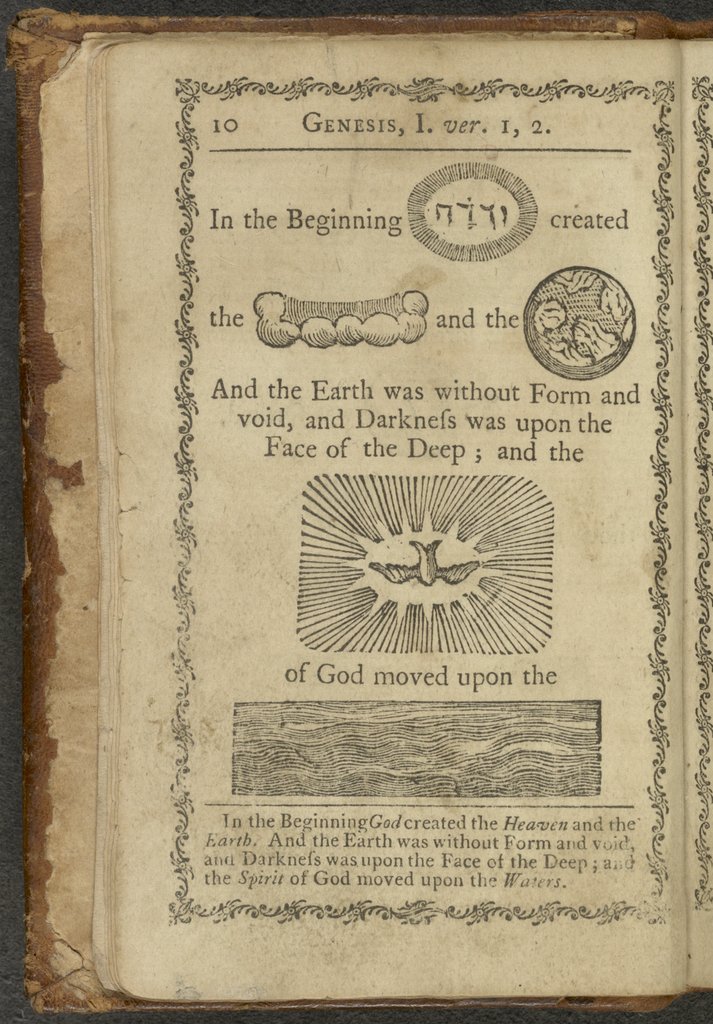

It just so happens that the fashion for hieroglyphs and Egypt roughly coincided with both the Industrial Revolution and the so-called Great Awakenings, or Christian revivals. At the same time, we see a profound shift in attitudes towards pedagogy — especially in regard to the education of children. In this climate emerges a rather short-lived but incredibly popular genre of children’s literature, the hieroglyphic Bible. Of course, these Bibles were not written in Egyptian Hieroglyphs, and neither were they written in rebuses, as were the hieroglyphical broadsides that appeared at about the same time. These hieroglyphic Bibles were part of a new kind of literature designed to teach children via pictures and pictograms — a method that nowadays doesn’t sound particularly groundbreaking, but was rather novel in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

1

2

Unicorns, FTW

These abridged pictographic Bibles were intended ‘to give [children] an early taste for the Holy Scriptures’, wrote Isaiah Thomas in the preface to his Hieroglyphics Bible, published in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1788, just five years after the first English-language edition appeared in London.

Archive.org

Archive.orgBut these English language editions were by no means the first. That accolade goes to a German edition, printed in Augsburg by Melchior Mattsperger, in 1683. Then followed editions in Dutch and French.

1

2

BSB

BSBWhat are they good for?

Once described rather dismissively as ‘curious little books with quaint woodcuts’, these early hieroglyphic Bibles were among the first texts designed specifically for children. These early abridged Bible texts were used not only to familiarize children with the principal Bible stories, but were also used in teaching children to read and write. ◉

Exciting news: After a decade, ILT’s annual Favorite Fonts is back. The list will be published in the ILT email newsletter on January 12. We also have some amazing fonts & books giveaways coming soon. Sign up to the monthly newsletter and never miss out. Oh, and signing up now ensures you’ll be entered into the 432-font giveaway!

Exciting news: After a decade, ILT’s annual Favorite Fonts is back. The list will be published in the ILT email newsletter on January 12. We also have some amazing fonts & books giveaways coming soon. Sign up to the monthly newsletter and never miss out. Oh, and signing up now ensures you’ll be entered into the 432-font giveaway!