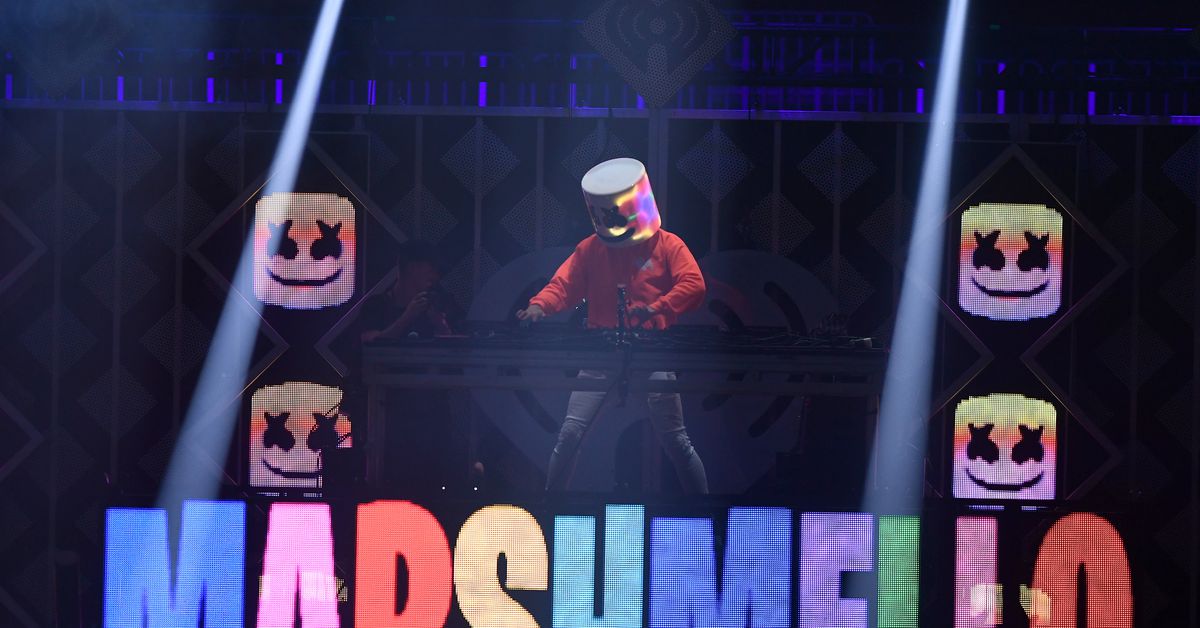

The other day, the electronic musician Marshmello, real name Christopher Comstock — who wears a white, marshmallow-shaped helmet on his head while he’s performing or in public (and at presumably no other times) — stopped by Pleasant Park for his biggest performance yet: to 10 million virtual people in the massively popular battle royale game Fortnite. It was, by all accounts, a resounding success. Players loved the 10-minute, no-weapon experience, and according to the concert discovery service Songkick, the event drove a 3,000 percent page view increase on Marshmello’s page and made him the most visited artist on the platform.

“Marshmello has had more fans looking for tickets on Songkick during the past 4 days than he’s had over the past 3 months combined,” the company wrote in a blog post. According to Social Blade, the social media analytics company, Marshmello saw a 62,000 follower increase on Twitter and a 5,200 growth on Twitch the day after the concert; two days after that, Comstock gained nearly 260,000 new followers on Instagram. Those gains were his biggest single-day follower jumps in February. Comstock was enthused, too. “Holy!!! We just made history today. We can all tell our kids one day that we attended the first ever virtual concert @FortniteGame,” he tweeted that afternoon.

We made history today! The first ever live virtual concert inside of @fortnite with millions of people in attendance. So insane, thank you epic games and everyone who made this possible! pic.twitter.com/xdaNGnyMr9

— marshmello (@marshmellomusic) February 2, 2019

All these people tweeting about “oh this person did this back in 1965” or “this was done before” I get it but no one has done it to this magnitude besides @FortniteGame who else had a full interactive set where over 10 million players got to play?

— marshmello (@marshmellomusic) February 3, 2019

Comstock corrected himself shortly thereafter; though it was probably the largest virtual show in history, the concert in Fortnite certainly wasn’t the first. There’s a rich history of concerts happening in virtual spaces, going all the way back to the early 2000s.

In the early 2000s, after the dot com bubble had burst and before the financial crisis caused by subprime mortgages and greedy bankers ravaged America, there flared a quiet moment of techno-optimism. It was a brief period when every reputable institution wanted to make their mark in the new digital realm of Second Life, an online playground which sought to be a virtual analog to real life. Even orchestras got in on the gold rush. In 2007, four years after Linden Lab released Second Life to the public, a group of amateurs in Leeds, England, and a chamber group in Cleveland had used the game to put on a concert for the public — although that year the highest-profile group to perform a live concert in Second Life was the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, the oldest professional orchestra in England.

The difference between a virtual concert and, say, a radio broadcast, is one of form: The melodies are transmitted in much the same manner, but the main distinction is one of presence. (The performance is also live, and not recorded.) To attend a virtual concert means to travel somewhere, even if that place is virtual. In digital space, the vehicle you drive is called an avatar — a virtual representation of your body.

“It is through this affordance of embodiment that people, places and things are made concrete, tangible, and present,” wrote the researchers Ulrike Schultze and Matthew Michael Leahy, both of Southern Methodist University, in a 2009 study about presence in Second Life. Presence, they continue, is made up of two things: “telepresence,” which they define as “the sense of being there,” and “social presence,” which is the sense of being together with others. In Second Life, they found that people “enacted multiple avatar-self relationships and cycled through them in quick succession, suggesting that these avatar-self relationships might be shaped and activated strategically in order to achieve the desired educational, commercial or therapeutic outcomes.”

In other words: they felt like they were there, and that they were their avatar. So much so that Second Life was both the first virtual space to make a woman a real-life millionaire from selling virtual real estate and the first place to get an avatar who only played in Second Life a real-life record deal. Bite Communications held the first virtual press conference by a Fortune 500 company; Redzone, a band from the UK, became the first group to do an entirely virtual tour, which happened in Second Life, too.

Other services have done a version of this, too. After Second Life, there was Sony’s PlayStation Home, which debuted in 2008, two years after the Playstation 3 was launched. Each user had an avatar and an apartment, and from there they could mingle with the other players for the seven years the service was online. The UK rapper Dizzee Rascal played a concert there in 2009. According to a release from the time, he spent time after the show mingling with the guests “trying to meet as many people as possible.” Then there was Turntable.fm (2011-2013), a now-defunct social media site that allowed users to create rooms where they’d DJ and also could mingle with the other people who stopped by.

The latest large virtual concert took place this year: in January, less than a month before Marshmello played Pleasant Park, Minecraft hosted Fire Festival 2019, a live, virtual music festival held entirely inside the game, headlined by Hudson Mohawke, ARTY, Luca Lush, and Ekali.

Virtual worlds have always been a place just beyond real life where you imagine yourself into being. Nine years ago, the journalist Jenn Frank wrote a beautiful essay about her diagnosis of agoraphobia and her sudden role as a caregiver to her ailing adoptive parents. Second Life became a safe place for her. “An agoraphobic panics because she cannot estimate where she is in space and time,” Frank writes. “I don’t mean to say that the stigma about Second Life is true, but maybe it is true for me. Maybe I am so consumed with living other people’s lives out for them, I have to transmit myself to an imaginary world to feel as if I could live my own.”

A few paragraphs later, Frank’s friend asks her, why? “The same reason anybody does anything—to feel as if she might not be turning, turning, turning, on this uneven axis in the dark,” she says.

We live there, in the quiet dark of real life. It’s where the last concert I went to was held: There were other people milling around in the foyer before, spending money at the bar on overpriced drinks, jostling each other on the floor while the artist played and the neon strobed and painted us like a canvas. It was all very physical. The artist finished; the house lights came up. We filed out, bumping into each other a little less this time, and made for taxis and the nearest subway station. When I got home I wasn’t tired yet, and so I got online to be with my friends for just a little longer.

After Marshmello played Pleasant Park, people around the world wondered whether this was the future. It’s hard to predict the future, and harder still to predict the future of music, but it’s easy enough to say two things about the experience: that Fortnite has undeniably become a quasi-physical space in the same way that Second Life is, and that concerts of this sort — which are accessible to nearly everyone, as Fortnite is free to play and available on just about every device — are, in fact, good and useful past their novelty.

“What makes me happiest about today is that so many people got to experience their first concert ever,” Comstock tweeted that day. “All the videos I keep seeing of people laughing and smiling throughout the set are amazing. Man I’m still so pumped.” Comstock must have been referring to their avatars, unless he could somehow see behind those masks.

https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/18/18229471/fortnite-marshmello-pleasant-park-live-music-future-past