You might remember a spate of news stories last year about Google Translate spitting out ominous chunks of religious prophecy when presented with nonsense words and phrases to translate. Clickbait sites suggested it might be a conspiracy, but no, it was just Google’s machine learning systems getting confused and falling back on the data they were trained on: religious texts.

But as the head of Google Translate, Macduff Hughes, told The Verge recently, machine learning is what makes Google’s ever-useful translation tools really sing. Free, easy, and instantaneous translation is one of those perks of 21st century living that many of us take for granted, but it wouldn’t be possible without AI.

Back in 2016, Translate switched from a method known as statistical machine translation to one that leveraged machine learning, which Google called “neural machine translation.” The old model translated text one word at a time, leading to plenty of mistakes, as the system failed to account for grammatical factors like verb tense and word order. But the new one translates sentence by sentence, which means it factors in this verbal context.

The result is language that is “more natural and more fluid,” says Hughes, who promises that more improvements are coming, like translation that accounts for subtleties of tone (is the speaker being formal or slangy?) and that offers multiple options for wording.

Translate is also an unambiguously positive project for Google, something that, as others have noted, provides a bit of cover for the company’s more controversial AI efforts, like its work with the military. Hughes explains why Google continues to back Translate, as well as how the company wants to tackle bias in its AI training data.

This interview has been edited for clarity

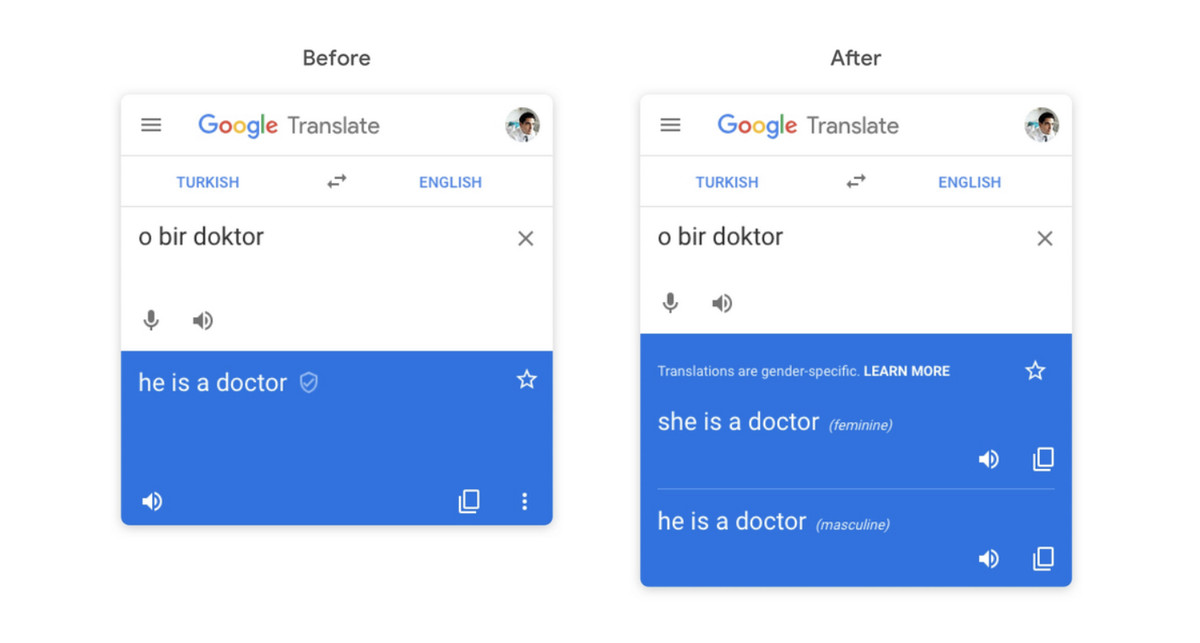

One big update you made recently to Translate was offering gender-specific translations. What pushed you to do that?

That’s two motivations coming together. One is a concern about social bias in all kinds of machine learning and AI products. This is something that Google and the whole industry have been getting concerned about; that machine learning services and products reflect the biases of the data they’re trained on, which reflects societal biases, which reinforce and perhaps even amplifies those biases. We want, as a company, to be a leader in addressing those problems, and we know that Translate is a service that has this problem, particularly when it comes to male / female bias.

The classic example in language is that a doctor is male and a nurse is female. If these biases exist in a language then a translation model will learn it and amplify it. If an occupation is [referred to as male] 60 to 70 percent of the time, for example, then a translation system might learn that and then present it as 100 percent male. We need to combat that.

And lot of users are learning languages; they want to understand the different ways they can express things and the nuances available. So we’ve known for a long time we’ve needed to be able to show multiple translation options and other details. This all came together in the gender project.

Because, if you look at the bias problem, there’s no clear answer to what you can do about it. The answer is not to be 50 / 50 or random [when assigning genders in translation], but to give people more information. To just tell people there’s more than one way to say this thing in this language, and here are the differences between them. There are a lot of cultural challenges, and linguistic challenges in translation, and we wanted to do something about the bias issue while making Translate itself more useful.

What problems are you going to tackle next then, in terms of both bias and nuance?

On the fairness and bias issue there are three big initiatives. One is just doing more of what we just launched. We have full sentence translation with genders, but only launched with Turkish to English. We want to improve the quality of that and expand to more languages. We did single word for some languages…

A second area is document translation. This is where there’s bias, but it requires a very different response. For example if you take a Wikipedia article about a woman in another language and translate to English, most likely you will see a lot of pronouns in English with he and him. That happens because you will get a sentence that’s translated in isolation, and the source language won’t make clear the gender, and so more often than not you will get he / him added in as default. Now, that’s a particularly offensive thing when you get it wrong, but the way to address that is completely different to what we launched last year. In this example it’s possible to get the right answer simply from the context [of the rest of the document]. So that’s a research and engineering problem to fix that.

The third area is addressing gender neutral language patterns. We’re in the middle of a lot of cultural turbulence right now, not just in English but in many, many languages that are gendered. There are emerging movements around the world to create gender neutral language, and we get a lot of inquiries from users about when we are going to address that. The example often cited is the singular use of ‘they’ in English. It’s increasingly common even if it’s not actually accepted in textbooks and style guides, referring to someone by saying ‘they are’ as opposed to ‘he is’ or ‘she is’. This is also happening in Spanish, French, many other languages. Really, the rules are changing so fast that even experts can’t keep up.

Something curious that happened last year with Google Translate was people discovering that if you inputted nonsense words it would spit out snippets of religious text. It became a slightly viral phenomenon, with people projecting all sorts of bizarre interpretations onto it. What did you make of it all?

I wasn’t surprised it happened, but I was at the level of interest in people’s response. [And at] the conspiracy type stuff, about Google encoding mysterious messages about secret religions, space aliens, and what have you. What it really illustrates, though, is a general problem with machine learning models, that when they get unexpected input they behave in unexpected ways. This is a problem we’re addressing, so that if you have a nonsensical input, it won’t produce sensical input.

But why did it happen? I don’t believe you ever offered an explanation on the record.

Usually it’s because the language you’re translating to had a lot of religious text in the training data. For every language pair we have, we train using whatever we can find on the world wide web. So the typical behavior of these models is that if it gets gibberish in, it picks out something that’s common in the training data on the target side, and for many of these low-resource languages — where there’s not a lot of text translated on the web for us to draw on — what is produced often happens to be religious.

Some languages, the first translated material we found were translations of the Bible. We take whatever we can get and that’s usually fine, but in a case where gibberish goes in, often this is the result. If the underlying translation data had been legal documents, the model would have produced legalese; if it was aircraft flight instruction manuals, it would have produced aircraft flight instructions.

That’s fascinating. It reminds me of the influence of the King James Bible on English; how this translation from the 17th century is the source of so many phrases we use today. Do similar things happen with Google Translate? Are there any odd sources of phrasing in your training banks?

Well, sometimes we get strange things coming from internet forums; like, sometimes slang from gaming forums or gaming sites. That can happen! With the larger languages we have more diverse training data, but yes, sometimes you get rather interesting slang from all corners of the internet. I’m afraid no specific examples come to mind right now…

So, Google Translate is particularly interesting as, at a time where AI is getting into trouble because of how and where it’s being deployed, everyone agrees that translation is beneficial and relatively unproblematic. It’s utopian, even. What do you think Google’s motivation for funding translation is?

We’re a fairly idealist company and I think the Translate team has more than its fair share of idealists. We work hard to make sure what you said remains true, which is why it’s important to fight bias and look for misused translation that could be harmful.

But why does Google invest in that? We get asked that a lot and the answer is easy. We say our mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible, and that ‘universally accessible’ part is very, very far from achieved. As long as most of the world cannot read the information online, it’s not universally accessible. Google, to achieve its core mission, needs to solve translation, and I think the founders recognized that more than a decade ago.

Do you think that’s possible, though, to solve translation? There was a recent article in The Atlantic by the famous professor of cognition, Douglas Hofstadter, pointing out the “shallowness” of Google Translate. What did you make of his critiques?

It was fair and true what he pointed out. There are these issues. But they’re not really at the forefront of our concern, because in reality they occur only a small percentage of the time in translations we see. When we look at typical texts that people try to translate, those aren’t the big issues right now. But he’s certainly right that to really solve translation and be able to translate at the level of a skilled professional whose knowledge about a domain and its linguistic issue, some major breakthroughs are needed. Just learning from examples of parallel text will not get you to those last few percentages of use cases.

It’s been said for a long time that translation is an AI complete problem, meaning that to fully solve translation you need to fully solve AI. And I think that’s true. But you can get to a very high percentage of problems solved, and we are filling out that space right now.

https://www.theverge.com/2019/1/30/18195909/google-translate-ai-machine-learning-bias-religion-macduff-hughes-interview