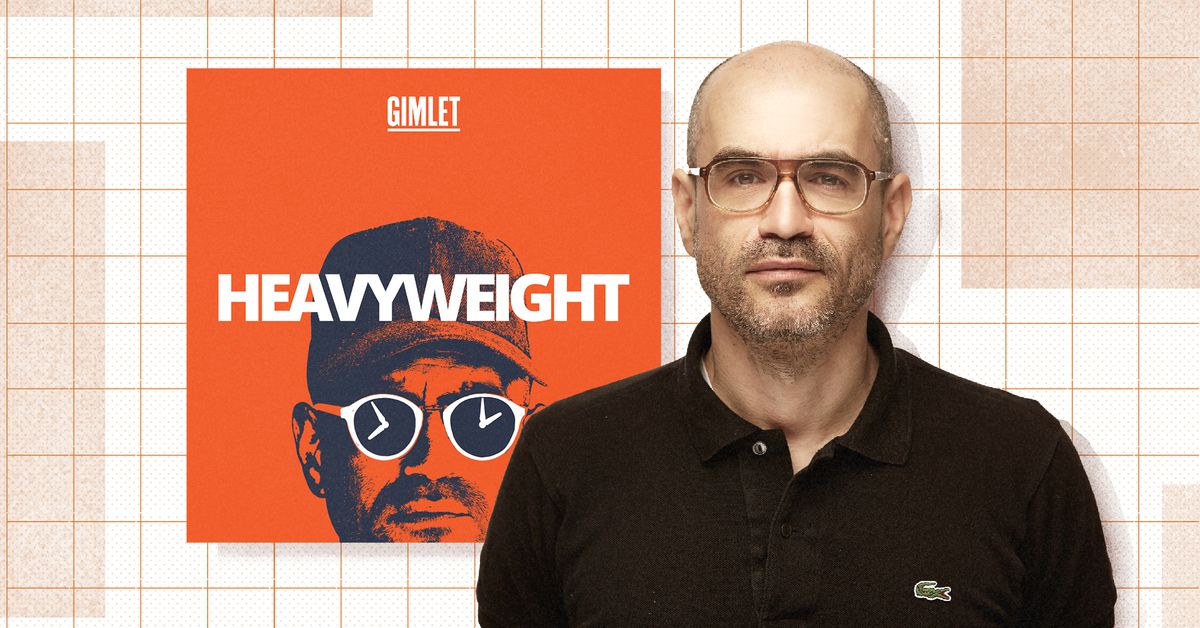

I love the podcast series Heavyweight, which started as a Gimlet Media show in 2016 and is now part of Spotify’s podcast empire. It’s funny, well-scripted, and surprising. Also, it’s heart-warming. I need it! On the show, host Jonathan Goldstein assists his guests in confronting unresolved past conflicts, which can range from genuinely traumatic experiences to smaller spats.

The fourth season premieres this week, so I spoke with Goldstein about his process for creating the show, what he looks for in guests, and, of course, whether he buys this idea that we’re all living through the “golden age of podcasts.”

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Season four started this week. How long have you been working on these episodes?

When last season ended, literally the next day, we were going over our story pitches, the things that had come into us. But even beyond that, there were a couple stories — actually, almost half the stories, at least three of the stories — were stories that weren’t ready last season for various reasons, just because they were more of a long-term commitment. So some of the stories in this season have been incubating for several years. The difficulty is that you’re dealing with people that have been putting things off for years, and that’s a part of the story, so it’s going to be baked into the actual trick of getting things in on deadlines.

The story of my friend Marie-Claude, for instance. We were childhood friends, and a couple years ago, she decided, the kids were grown up. She never really had a career and she wanted to become a real estate agent and she had passed all the criteria except for the grade 11 math equivalency. And Marie-Claude and I had gone to high school together, and we were both terrible at math and were kind of math-phobic. So now it’s one of those nightmares where you have to go back to school, and she had to try to go to class to gain the high school math equivalency, and she just put it off and put it off. We couldn’t even do it last season. That is hopefully, it’s still a little up in the air, but hopefully, it’s going to be a part of this season. That’s a long answer to say that, yeah, some of them have been ongoing for years.

How up to the wire are you working on the episodes? Do you bank them all before the season premiere?

No, like, it’s coming out on Thursday, and we’re still deep into the mix, and even retracking stuff, hearing holes in plotting, and in some ways getting a little neurotic and second-guessing ourselves. All those are the things that I guess go along with publishing.

How big is your team?

This season, I have two full-time producers, and we had a producer come on a couple of months ago. We also have an editor that we share with another show. Then there’s a lot of people that we have sit in on edits, like after I get off the phone with you, we have an edit with Alex Blumberg. So when he’s available, I love getting him in on a more final edit, where we’re getting closer to the finished product. I love having his ears on it. And then sometimes we’ll bring in people from other shows. Like for this first episode, PJ Vogt sat in on it. It’s really cool being able to ask the people that you work with whose stuff you admire, and whose taste you like and trust, to sit in. My wife, Emily, will also listen to final-ish versions of it to just hear if it’s missing anything. As you know, you get so into the weeds, sometimes you don’t see the big things.

What’s the scripting process like, and who do you trust with your script edits?

It’s all part and parcel. Normally with radio production, or the way that I was taught it, you begin with the best tape and then you write around the best tape. Sometimes these stories don’t always happen that way.

It really comes together as a piece with the tape. A lot of the tape that isn’t even necessarily funny will begin to feel more funny when it’s written into in a particular kind of way to highlight sometimes my own kookiness.

In the beginning, like the first couple episodes, I was just by myself and I was just starting from the ground up. And now with producers, they’re able to present with the editor what we call the playthrough, where they’re able to present a kind of rough with preliminary, provisional writing and tape. And they have grown into the role, and they’re taking more liberty with the writing and being able to crack jokes is very exciting, fun to hear.

Then it just goes through so many drafts. We work through Google Docs. It’s weird. Before I worked in radio, I was writing mostly. I had written a book of short stories and stuff, and it’s just so solitary, but with this, also because of the technology of the Google Docs, we’re all kind of in it, oftentimes. There’s a point in the process where I have to be alone with it. But a lot of times, we’re just kind of in it recrafting jokes and trying to make each other laugh. That’s just to say there’s no steadfast rule. Even though we’re in the fourth season, I feel like I’m still trying to figure it out.

There’s one episode in the season that’s a more personal one about my relationship with a psychiatrist that I saw through my 20s. That one started with writing. With a story like that, I think because it was so personal and in my head, it started off with writing, and that was one where it was just me sitting by myself. It was more of how you’d think of a personal essay.

I always imagined you, as a writer, being precious about your words, so it’s great that you trust multiple people and that they write, too.

I do and also like, they kind of begin to learn my voice more, or that voice is developed as the seasons progress. We try to find the right balance between the jokiness and the sincerity, and sometimes you hit the mark, but the best ones are when you feel like you’ve nailed it, when that alchemy is kind of perfect.

I guess it’s also turning to people for their strengths, like knowing that certain people are really good at big-picture thinking. Some people are really good at jokes. But even if it’s not me sitting at an old-timey roll-top desk with a quill and paper, even if we’re in on it as a group, there’s just a lot of deliberation over word choice and just getting it right. It’s a little bit of a different process than writing for yourself or writing for the page because oftentimes, it’s stuff that starts off as sort of Baroque or even flowery. You want to make beautiful writing, and you want to be writerly. But you also want to be a decent broadcaster, which means being inclusive and making sure that your points are clear, and you’re coming across to as many people that you can.

Sometimes there will be a joke that none of my producers will even know what the hell I’m talking about and that sometimes feels okay because you’ve got to throw in one for yourself. But other times, it’s sort of like, well, if they’re not going to get it then no one is going to get it.

In many of your episodes, you speak with your friends and family. Have you exhausted them all yet?

Well, now I’m on the tail end of that train because the story about my friend Marie-Claude might be the end of that. And it’s complicated in all the ways that working your friends can be complicated. There’s another story, which began with a friend of my wife, this guy who I met at a wedding. We were having a cigarette outside, and he told me this whole story. So now that I’m done with my friends, I have to get into my wife’s friends.

I think initially, making that jump from the first season where it was pretty personal and within my comfort zone in terms of my small group of friends and family, going into the second season, where things were coming across the transom from people that I didn’t know and were sort of looking at me as something of an expert, was very daunting and kind of scary. But what evolved, I guess, was just trying to give them the thing that they need and also stumbling my way through things and trying to even allow the stumbling and some of the awkwardness to come through, as almost a way of kind of shielding the subjects.

There were certain things that I wasn’t even hearing as funny that a producer would say, “Oh, that’s hilarious.” Like, where you dropped the tape recorder. I would cut that out, but they’re like “That’s really funny that you dropped the tape recorder.” Those moments of vulnerability, or just extreme unprofessionalism, or being clumsy, become the thing that people relate to. The thing that was nice to see is that sometimes you could try to make a joke and you can spend a lot of time crafting it, and then other times, all you need to do is drop a tape recorder on the floor and something genuine comes across. It’s funny, but it’s also vulnerable, and people like that just as much, if not more, sometimes.

Did you do any prep or research into how to mediate conflict? It seems like a lot of pressure to have to help a stranger resolve an issue from their past.

It’s basically like I throw myself on the grenade. It’s hard because, like I said, people have been putting this stuff off for so long. Having come from a fiction background, the thing that I was drawn to about it was that no one could get hurt. It was all very theoretical. You were just shaking up all the ants in the ant farm, or whatever, in your mind.

I guess I just feel like the first rule of the whole thing is that I don’t want to make the situation worse. Like if I feel like I can’t help, or I’m not helping, I don’t want to just intrude for the sake of intruding. Sometimes it’s a super simple thing. Something that to the person at the center of it, the subject, it seems like such an insurmountable thing, when really it’s worth a couple awkward hours to get something off your head for the rest of your life.

I don’t know if you’ve heard the episode about the woman Julia who wanted to confront the girls who bullied her when she was in junior high. They showed up at her door, and they rang her doorbell, and she was too afraid to answer the door. She’s been telling the story for so long, and that’s where the story ended for her: “They rang the doorbell. I don’t know if they wanted to bully me some more or apologize, and I never found out, and I guess I never will.” For me, it just seemed to beg the question of, “Okay, well, let’s find out.” For her, that was the craziest thing she’d ever heard. This allowed her — to actually give her permission to ask those questions — the power that that allowed her began to snowball, and she began to get bolder and bolder. Sometimes it’s just giving people context, giving them a forum to do the work themselves and you just stand back, that’s the best. If you can, kind of create a forum where someone can talk to a person that they really want to talk to, and the less work you have to do, the better it’s going to be.

One episode I really enjoy is about someone who is banned from a pizza shop, without giving too much away. How hands-on are you in episodes like those where the guest is a stranger to you? What’s the process like to get them to open up?

He wrote an email that really struck me. It just seemed as though it was written by some 19th century count or something. It was that formal. I thought, “Oh, this guy’s a real character,” in a good way. But yes, he reached out to us, and he was very open. Also at that point, you’re getting people who know the show, so he knew what he was getting involved in. He knew the sensibility. He saw the comedy in it, so I felt a little more free than I otherwise would be to kibitz with him a little bit, or treat him sort of like my nephew. He also knew Gregor and got a kick out of him and didn’t find Gregor to be scary, or too harsh or whatever. But I think that created a nice dynamic. If I didn’t feel like Joey had a sense of humor about it, then I think I would have been maybe more trepidatious to be as hand-holdy or even as didactic as we were with him.

One episode I wanted to ask about was the first episode of season two in which you reconnect your friend Gregor to the musician Moby. How has that episode aged now that Moby has been effectively canceled because he claimed to have dated actress Natalie Portman?

Is he officially canceled?

I think he’s on the verge of cancellation, if not all-out canceled.

There’s something, I don’t know if it will work in his favor ultimately, but something a little absurd about him. There has been some feedback in the wake of all of that stuff about that episode. It is interesting because the story has not changed, but the way that people hear it has. I remember when it aired, people found it very sort of generous and noble and brave of Moby to talk about his battle with depression and being suicidal. He was coming from a very unique vantage point. There’s not many among us who can talk about having it all and still just being profoundly unhappy. I thought that was interesting. We weren’t setting out to do a story about a celebrity. It was just a plot point in Gregor’s life. My friendship with Gregor was the thing that I found the most interesting, and Moby was going to be a part of that story, but really it was a significant part of that story. But afterwards, people saw the things that he said differently. I don’t know if you listened to it again in the wake of his cancellation.

I didn’t listen after his cancellation, but I did listen a second time, and it felt super cringey to hear Moby talk about how he basically relied on African American folk songs to make a platinum album and launch his career.

We had a whole other digression. That’s the editing process, like we went back and forth on do we include more editorial on the business of what he’s actually doing. Then it just felt like it wasn’t really part of the story we were telling. But I will say, though, that in the wake of the whole thing with Natalie Portman and everything, people just heard what he was saying differently. That is interesting, and that is what changes the moral authority of someone’s voice. People were like, “Well, wait a minute. Why didn’t he just go to the storage unit in Queens and dig it up, or pay someone?” They were just questioning Moby more, it seemed like, in the wake of the whole thing.

You have a whole schtick on your show with the ads that comes off, to me at least, as enthusiastic. That’s different than most podcasters. What’s your perspective on host-read ads, especially coming from a public radio background.

Especially coming from a very unenthusiastic background. I’m not a very enthusiastic person, so that is nice of you to say that you hear genuine enthusiasm in my voice. I think a part of it is that in the midst of the work of making the series, when I go into the studio with Jorge, our editor, it feels playful and it’s kind of a break. Coming from public radio, coming from a place where you just never thought there was going to be any money in this, for making audio documentary. There’s just something, like, “Holy cow, I actually have a sponsor to do this kind of thing.” Just seems crazy in a way.

I guess it’s a chance to play. I will also say that what’s nice, too, is we take a kind of ironic approach to the ads. Our hope is that our ads are going to look more tongue-in-cheek than other shows. When sponsors come to us, they kind of know what they’re getting into, which also sort of allows us to feel more free and playful with it.

Do the sponsors ever push back on what you deliver? How does that relationship work?

It really depends what company we’re working with. Some of them say, “Do whatever you want.” Others, like I was just given some copy that was just like, “This is the copy and you have to read it.” And I’m like, “Okay, great.” Sometimes you just want to break into your voice and sometimes they’re open to that. Sometimes the companies come to us through intermediaries, like through other agencies, so there’s all kinds of cogs in the machine.

What’s nice is if someone on the team, somewhere along the line, is a fan of the show and they kind of know what they’re getting and they let you have fun with it or encourage you to have fun with it.

It’s nice to hear that I seem enthusiastic. Talking about public radio, all producers, all audio people were required to do pledge drives where you basically just come out and talk directly to the listener, and you say, you’ve got to give us some money. I just wasn’t very good at it. There was always just this level of irony with me that I kind of hid behind. I was just embarrassed. Maybe it’s a Canadian thing, or maybe it’s just a me thing, but to come out with your hat in your hand and say, “Hey, do you think you could give some money for this thing?,” just felt super uncomfortable to me. As a result, I was really bad during the pledge drive. Some people were really good at them, and I don’t think I was. So I don’t think I can really come out and sing the praises of product exactly, but I can kind of dance around it and do whatever it is that we do.

Yeah, because you don’t have to beg for money.

I really do feel like this is what allows us to do the thing we’re doing, so I feel pretty good about it.

You came up through public radio, then went to startup world at Gimlet Media, and now you’re part of one of the world’s largest audio companies at Spotify. Do you buy into this idea of it being the “golden age of podcasts”?

My take is, I would say that I was educated with a particular kind of skill in radio production that there just didn’t seem to be any market for. I worked at This American Life, I learned this particular thing, and now that there’s a world in which there’s a lot of really good stuff out there, and a person can make a decent living from doing it, it’s just something I never could have imagined.

I loved it, and I would have continued doing it for no money. I did a show — not that it was for no money — but I did a show for 11 years on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation with not the same kind of listenership, but I loved it. I would have just kept doing it because I love doing it. So to be in this environment that you want to interview me about the start of a podcast season just seems weird and great.

When I left This American Life, I went to Canada, and I was the only person using Pro Tools, really, at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. So the pond just seemed small.

https://www.theverge.com/2019/9/27/20885497/spotify-heavyweight-podcast-gimlet-media-jonathan-goldstein