After hearing the news that then President-elect Donald Trump had appointed a notorious climate change denier to lead the Environmental Protection Agency transition team in 2016, Nicholas Shapiro, an environmental anthropologist, penned an urgent email to a dozen or so fellow scientists.

He was worried that the EPA was about to be torn apart from the inside under Trump’s leadership. Others on the email thread were concerned that vital environmental data would be taken down from federal websites and destroyed. They’d just seen brutal attacks on science in Canada — irreplaceable scientific records were dumped in the trash under conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper — and they feared that something similar could happen in the US. So Shapiro took a cue from his sister, an organizer for the Women’s March, and tried to bring researchers together to mount an offensive.

“Does anyone know of any social scientists inside the EPA that might be able to document its dismantling?” Shapiro, now an assistant professor at UCLA, wrote at the top of his note. “It seems like it could be a humble contribution of our craft — just one stopgap idea that came to mind.”

The effort sparked by the email eventually snowballed into a movement to rescue key environmental datasets and information about climate change from government websites. Shapiro and his colleagues succeeded in connecting with scientists within the EPA to document the agency’s transformation into an antagonist to environmental efforts in the US. And in some cases, the scientists were even able to mitigate the damage.

The scrappy cadre of scientists is now a largely volunteer-based group called the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI). Their work is far from over, despite Trump leaving office, as they work to make sure another president can’t drastically remake federal websites or destroy data in the future.

Data Rescue

“Trump wanted to tear the EPA into little bits,” says Sara Wylie, an associate professor at Northeastern University who responded to Shapiro’s email. “We started talking on that email thread about what we might be able to do.”

The scientists worried that if records started disappearing, it would be harder to build on prior research or to use it to hold polluters accountable. On top of that, the public would lose information that could keep them safe.

In a matter of weeks, they launched “guerrilla archiving” events that made headlines for attracting hundreds of volunteers across the US and Canada who helped to identify and save environmental datasets. The EPA keeps records, for example, of the most dangerous substances at toxic Superfund sites that have been placed on a national priority list for cleanup. At each archiving event, volunteers identified important URLs and determined whether they needed to be manually backed up or if they could be harvested by the nonprofit Internet Archive, which stores a history of website changes over time.

The effort dovetailed with a collaboration called the End of Term Web Archive, which saves content on government websites before every presidential transition and makes it publicly available through the Internet Archive. They also collaborated with researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, who still house data that needed to be manually archived.

“It was really a public outcry of saying, this is public data,” Wylie says. “Federal government: This was paid for by taxpayer dollars. You don’t really have the right to delete or remove it.”

Beyond saving data, Wylie worked to make it more accessible to people. Over the past year, EDGI began aggregating data on the EPA’s enforcement actions to make it easier for communities to see where companies violated environmental law. Last year, they created report cards for congressional districts and found an enormous jump — a median 98 percent increase — in violations to the US Clean Water Act across 55 districts.

Website Watchdogs

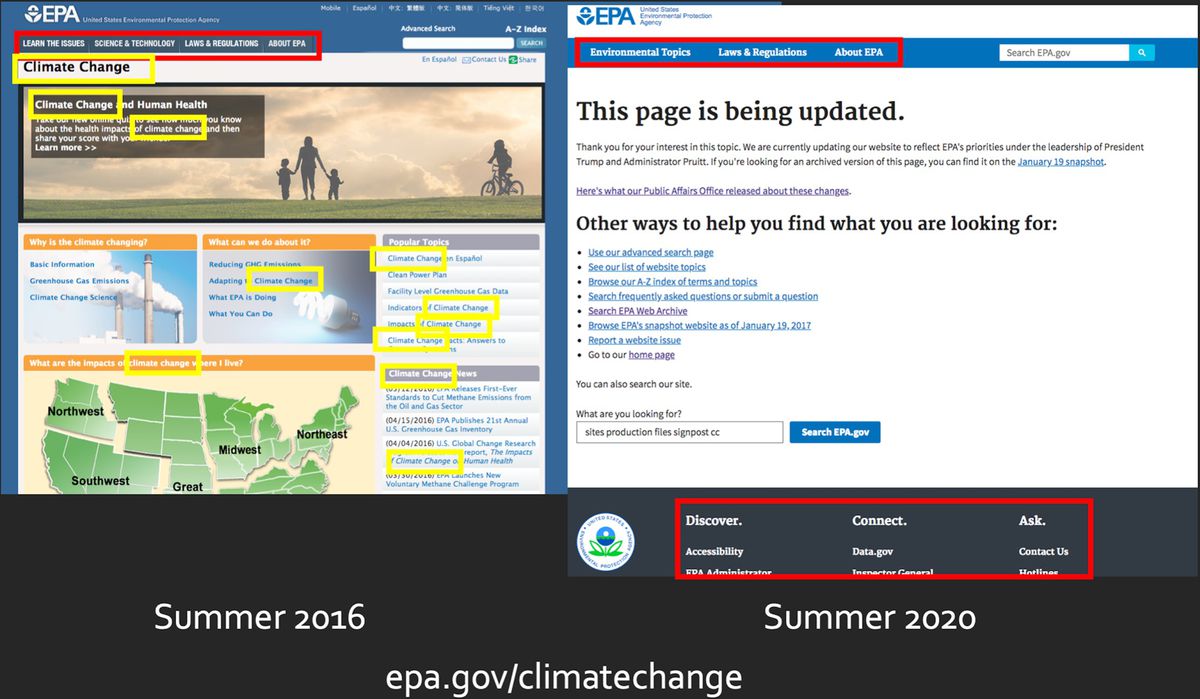

Soon after Trump stepped into office, EDGI noticed changes to government websites that made it harder to find information about climate change and pollution. Science agencies overhauled their websites, taking down pages and paring down information.

“You’re asking about a very hazy, fast-moving time,” Gretchen Gehrke, one of the recipients of Shapiro’s email and now a program leader for EDGI, tells The Verge with a laugh as she recalls the early days of the group’s work to monitor government websites. A five-person team was put together to monitor tens of thousands of web pages. “We were all working all hours of the night. Everybody had full-time jobs, and we’re working on this 40 hours a week on the side.”

Before the group developed more sophisticated software, it started with a version that flagged all kinds of changes to websites. In those early days, Gehrke and her small team had the tedious job of looking through what was flagged to sort out which changes were actually meaningful. “It was like searching for a needle in the haystack,” Gehrke says. “Every difference showed up — which, for a lot of pages, was a date stamp change or removal of an excess space somewhere.”

Typos and date stamps aside, Gehrke’s team found changes and deletions that could have grave consequences. Official websites not only reflect the priorities of agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency; they also are an important resource for the public to learn about issues like air and water pollution that impact their lives.

Months into Trump’s presidency, the term “climate change” was already disappearing from government websites, EDGI found. It also found that webpages for major environmental regulations aimed at protecting Americans’ air and water were taken down months before Trump’s administration even proposed rolling them back. Gehrke says that undermined the public’s ability to understand the rules and participate in public comment periods before they could be repealed.

When the National Park Service took down plans from its website about how individual parks would respond to climate change, Gehrke’s group sounded the alarm with a report on the deletion. Following that report, the NPS said that it had temporarily taken the information down to make it more accessible to people with disabilities — saying in a statement to EDGI at the time that it would bring the information back.

Storytelling for Science

As Trump attacked the EPA on his election campaign trail, Chris Sellers, a professor of environmental history at Stony Brook University, realized there was another crucial source of information that was at risk: the people who actually made science agencies tick. Months before he was elected, Trump called the EPA the “laughingstock of the world” and proposed funding cuts to the agency that were sure to lead to staff cuts.

Ultimately, more than 1,600 federal scientists left their positions during the first two years of Trump’s presidency, The Washington Post reported in January 2020. “Much of the expertise of the federal bureaucracy has fled in horror,” Michael Gerrard, founder and faculty director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University, told The Verge last year.

Hoping to archive the wealth of knowledge those people hold, Sellers and others at EDGI began confidentially interviewing staff at the EPA and OSHA. By June 2017, EDGI published a report compiling 60 confidential interviews. Morale among agency staff “plummeted,” the report showed. Their work was “paralyzed.”

A few months later, EDGI published an interview with Mustafa Ali, who led efforts to address environmental racism at the EPA, after his high-profile exit from the agency. When asked which programs and projects he was worried about at the agency, Ali responded: “I’m worried about all of them… There’s not too many places in the agency that I think this new administration has not placed some really tough times ahead of.”

Now, with a new president in power, more of the people who EDGI spoke to are willing to come forward with their stories. Since December, EDGI has slowly released previously anonymous individual interviews on a new website, apeoplesepa.org — now with names attached to the stories. The interviews aren’t just an indictment of the Trump administration’s attack on science; they also make up a library of lessons learned about how to serve people and the planet.

“In a time when you feel so many of these institutions are being trampled upon just willy nilly, to be able to do something towards reversing all that damage [has] been a really gratifying experience,” Sellers says. “It really helped me survive the Trump years.”

Some of the EDGI scientists’ initial fears came to fruition. By the end of Trump’s term, the use of the words “climate change” fell by almost 40 percent across websites for US federal environmental agencies. And access to as much as 20 percent of the EPA’s website was removed, according to EDGI. Trump’s administration rolled back more than 100 environmental regulations. And science agencies indeed suffered a brain drain. But EDGI celebrated some victories throughout Trump’s administration, and their work isn’t done now that someone else is in office.

All in all, EDGI and its collaborators managed to archive over 200 terabytes of data and content from government websites between fall 2016 and spring 2017. There was so much hype over the effort that EDGI members think they may have deterred the Trump administration from actually trying to delete data. The datasets that they took care to save, for the most part, stayed up on federal websites.

They’re still trying to keep that data safe for posterity. They don’t want the data to fall victim to any future administration’s whims. One approach they’re looking into is the so-called “distributed web.” It’s still a developing concept, but the idea would be to back up the data across a peer-to-peer network so no one person can control it. “There are so many copies [of the data] that it can kind of never be magically deleted,” Wylie says.

EDGI is also pushing for policies that provide high standards for web governance. Information on government websites should be archived and easily accessible, the group says in a report released in February. That means that even if a web page is taken down, its address should lead to an archived version of the page — not a “Page Not Found” notification. If knowledge is power, they want to make sure that people always have access to it.

https://www.theverge.com/22313763/scientists-climate-change-data-rescue-donald-trump