The Savannah Bananas’ Jesse Cole turned an unloved team into the hottest ticket in town. Now he has a lesson for every CEO who wants to turn a company around: Stop doing what people hate.

15+ min read

This story appears in the December 2019 issue of Entrepreneur. Subscribe »

Baseball is a game of tradition, and Grayson Stadium is as traditional as they come. The Savannah venue was built in 1926, back when game-day radio broadcasts were a new thing. The Boston Red Sox held spring training here, leading Hank Aaron, Babe Ruth, and Jackie Robinson to round its bases. For three decades, a local high school also took Grayson’s field for its annual Thanksgiving Day game against a military academy. And between 1984 and 2015, it was home to a minor league team called the Sand Gnats. This was all baseball in its classic form — orderly and staid, romanticized by purists.

Now? Things are a little different.

It’s the bottom of the second inning at Grayson Stadium on a muggy midsummer night this past August, and baseball is briefly on pause. The local team is now called the Savannah Bananas, and its four pitchers are lined up along the first-base line in their bright yellow uniforms, thrusting their hips back and forth to “That’s What I Like,” by Bruno Mars. Alex Degen, a 19-year-old pitcher from the University of Kentucky, is really getting into it. I got a condo in Manhattan. Degen thrusts left. Baby girl, what’s hatnin’? He thrusts right. Later, in the fourth inning, he’ll hand out roses to little girls in the stands. In the seventh, he’ll rip off his shirt atop the dugout.

Related: How 3 Entrepreneurs Convinced an NBA Star to Invest

And as he charms and preens, he’ll be just one part of a general circus atmosphere. They’ll toss oversize Dolce & Banana underpants into the crowd. A Summer Santa will drive a VW Bus around the bases. The break-dancing first-base coach will bust out his moves, and the team’s official, on-the-payroll high-fiving kid will high-five as many fans as possible. “I was shell-shocked when I first saw the Bananas,” says Degen, the pitcher, of his arrival in Savannah. “I was very skeptical. In college, baseball is serious. It took two weeks for me to realize this was fun.”

It didn’t come naturally to the team’s owner, either. Like many of his peers, he was once a baseball purist. Then, once he started investing in teams, baseball nearly wrecked his life. He was forced to sell his house and empty his savings account. He and his wife were $1.8 million in debt and sleeping on an air mattress. Things were desperate. But out of desperation came innovation. “We had to dramatically change the type of business we were in,” owner Jesse Cole says. “We needed to no longer be a baseball team; we needed to be an entertainment company.”

That meant fixing any aspect of the fan experience that didn’t inspire joy. And to his eye, there were many: from marketing to sales to stadium food to the sport itself. “Normal gets normal results,” Cole says. “So I thought, What would be abnormal at a baseball game? What will get people saying, ‘I can’t believe what I saw tonight?’ ”

Cole started wearing a yellow tuxedo to every game (and often around town, too) to stand out. He reinvented everything he saw. And in the process, he built this new team at an old, worn-out ballpark into Savannah’s hottest ticket. It’s so hot, in fact, that the team saw 20 percent growth in total revenues last season after years of 100 percent year-over-year improvements. More than 4,000 people pack the stands every night. Savannah’s mayor languished on the waitlist for more than a year before he was able to get season tickets.

As his team succeeded, Cole began crystallizing a philosophy he calls “fans first.” The idea is simple. At every step, you put yourself in the shoes of your customers and your employees, and you ask: Is their experience exciting or boring? Easy or complicated? Fun or frustrating? And if at any point it’s the latter, then you’ve got a problem. Now Cole is thinking even bigger. If “fans first” could work for baseball, why couldn’t it work for any company in any industry? “For every company that wants to take care of its culture, you want the best possible fan experience,” he says. “Stop doing what your customers hate.”

So that’s what the Savannah Bananas’ chief banana is preaching. Every business is born out of tradition. But what good is tradition if it isn’t making people happy?

Bananas owner Jesse Cole is in the crowds for every game.

Image Credit: Jason Frank

Cole is 35 years old, six foot one, banana thin, and unapologetically devoted to his cause. He owns seven yellow tuxes and three yellow top hats, which he wears on rotation daily. His confidence might read as cockiness if he weren’t such a goofball. “It was very Steve Jobs–esque, very Henry Ford,” Cole says of what he’d done in Savannah. “If you asked people what they wanted [in 1900], they would have said faster horses. No one said that the iPod was best for people or that the car was best for people. And no one else realized there was a problem with baseball.”

At first, Cole didn’t either. He’d pitched at an NCAA Division I college and assumed he’d go on to play pro ball. Then he tore his shoulder in his junior year. The injury was career ending, so he moved into coaching. “I had a big epiphany,” he says. “I hated watching the game.” Baseball, Cole realized, was painfully boring if you weren’t on the field.

But Cole wasn’t ready to let go. At 23, he became the general manager of the Gastonia Grizzlies, a team in North Carolina. And to understand the realm of baseball that Cole now occupies, it is important to pause here and understand the Grizzlies. Baseball is a many-tiered world, and Major League Baseball (with the New York Yankees, Los Angeles Dodgers, and so on) is at the top. Beneath that is Minor League Baseball (with its AAA, AA, and Single-A affiliate teams), which is followed by regional independent leagues (where players aspire to make the minor leagues). Then, at the very, very bottom, there are teams like the Grizzlies. They play in collegiate summer leagues — in this case, an organization called the Coastal Plain League — where college players who aspire to go pro can hone their skills (for no pay) while school’s out.

Collegiate summer teams can be thankless places. They are businesses; their owners would like to make money. But their players’ talent is of varying quality, which makes tickets a tough sell. When Cole joined the Grizzlies, he had no management experience and the Grizzlies had no prospects. The team averaged a scant 200 fans per game, had lost $100,000 the previous season, and had $268 in the bank. “I never forgot seeing that bank account and thinking, What are we going to do?” Cole recalls.

To answer his question, Cole returned to his epiphany from the previous year. Baseball was boring, and boring didn’t sell. So what did? He had an idea: Fun! What if the primary draw wasn’t hits and runs, but silly dancing and a dunk tank during the seventh-inning stretch? Between every inning, there could be a wacky promotion to amuse the crowd — a kid smashing a pie in his dad’s face, or a bunch of cheerleading grandmas. Lower-tier baseball has long included some of this stuff, but Cole wanted to make it the main attraction. Gastonia’s owner was incredulous, but he had nothing to lose. Cole took the lead.

The plan worked. Attendance skyrocketed until Gastonia ranked fourth in the country among its peers and was seeing six-figure growth. In 2014, at age 30, Cole purchased the team. Later that year, he and his new fiancée took a vacation to Savannah, where they went to see the city’s minor league team, the Sand Gnats, play at Grayson Stadium. As it happened, the Sand Gnats were leaving town due to lack of interest. In their departure, Cole spotted an opportunity to double down on his playbook. He could create a new team in Savannah, replicate his success from Gastonia, and own two booming teams. So in 2015, he worked out a deal: The Coastal Plain League (in which the Grizzlies played) sold Cole the expansion rights for a new team, and he installed it in Savannah’s Grayson Stadium.

But Cole, it seemed, was the only person in Savannah excited by summer collegiate ball. “The skepticism from the city was unbelievable,” he says. “We were trying to share our story” — and the success in Gastonia — “but no one knew who the Grizzlies were.” Cole remembers sitting around the stadium offices with his 24-year-old president and three 22-year-old interns calling every business in town, looking for sponsors. Nobody called back, which presented Cole with a catch-22. People needed to see the story to understand it, but to do that you needed to sell tickets. He couldn’t create an innovative fan experience without fans.

By January 2016, Cole’s personal and professional finances were a wreck. Cole still owned the Grizzlies, and he and his then fiancée, now wife, had just finished building their dream house in North Carolina. There was no way to offload the Savannah team without taking a giant financial hit, so they had no choice but to sell the house, empty their savings, and move to Savannah. They set up in a dilapidated duplex and inflated an air mattress. Then they got to work. “We were going to look at all the problems in baseball,” Cole says, “and try to solve them.”

Players film a video to promote their upcoming playoffs.

Image Credit: Jason Frank

To drum up local interest, Cole put out a citywide call to name his new team. Only one good suggestion came in, but it was a winner. “We knew 1,000 percent the Bananas was it,” Cole says. “You can’t say ‘Savannah Bananas’ without laughing in your head a little bit.” Savannah was laughing, too — but at Cole, not with him. “When we came out with the name locally, we were crucified. We got hate mail,” he says. He was called an embarrassment on Twitter. People said he’d never sell a ticket. But Cole had faith. “When you create attention, you’ll be criticized. But if you’re not criticized, you’re not doing anything.”

He was right. When the Bananas’ logo was revealed, it was so absurd — a rough-and-tumble banana wielding a bat — that it went viral. The team trended on Twitter. Good Morning America called. Merch sold like crazy. “Everyone knew who we were,” Cole says.

Creative branding was only part of Cole’s strategy. To fill seats, he needed to structurally rethink the fan experience. So he asked himself a question: What do fans hate about attending a baseball game? He had many answers. They hate the confusing tiers of ticket prices. They hate how much food costs. They hate the constant marketing.

To fix this, Cole created a new value proposition. Almost all tickets would be general admission and priced the same, and they came with unlimited burgers, dogs, chicken sandwiches, sodas, popcorn, and cookies. (Beer and a few other items would still cost extra.) Now nobody felt nickel-and-dimed, and he was able to charge $15 per ticket — far more than other teams, but still turning a profit. Every game would be full of surprises, with new gags and games. Players would line up to greet fans on the way into the stadium. And to market these new offerings, Cole decided to be as un-pushy as possible: The team’s aspiration would be to immediately wean itself off direct marketing.

“We shifted to a pure content approach,” says Berry Aldridge, the Bananas’ 25-year-old vice president. “And we’re not going to ask you to buy at the end. It’s a pure give. Assume your buyer is smarter than you think, and they’ll take the next step themselves.”

Related: Want a Tiger Woods Comeback? All It Takes Is the Right Mindset.

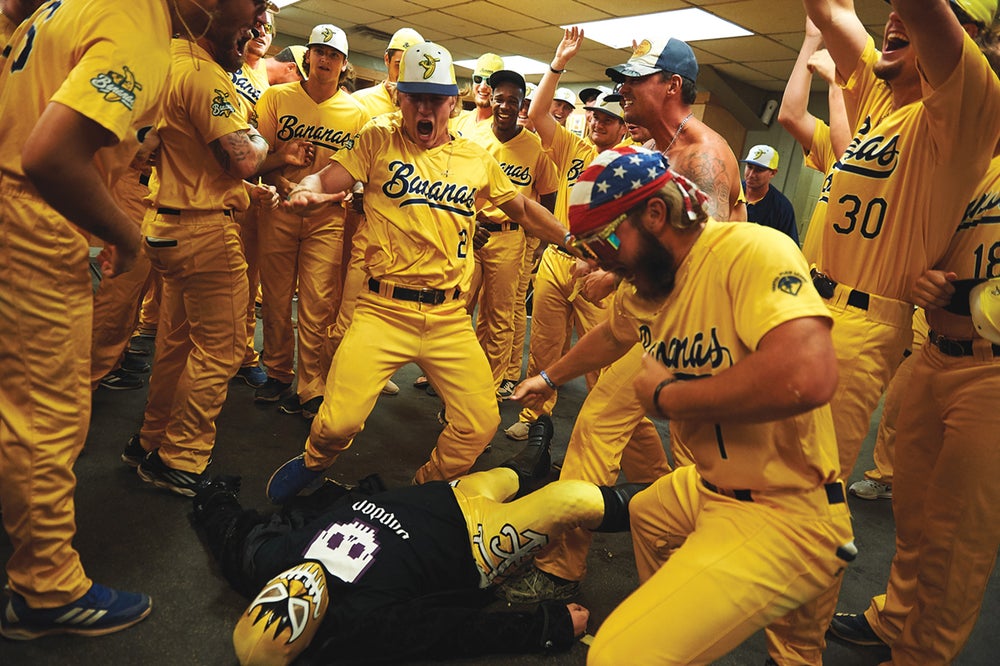

To promote the 2019 season, for example, the team released a video of the players dancing to Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” while leading a horse around the infield. To promote the playoffs, it made a video of the team fake-fighting with a Mexican wrestler in the locker room. Efforts like this work so well that Aldridge didn’t make a single cold call this year. Most games are sold out four to six months ahead of time. There’s a 435-person waitlist for stadium club memberships, which include catered food and an open bar. And while you’re on the waitlist, you’re not languishing — because the only thing sports fans hate more than buying tickets is not being able to buy tickets. So multiple times during the year, the team throws free events with food and drinks for waitlisters.

“Keeping them engaged is better than just having them in the void,” Aldridge says. Or as Cole says, “Don’t talk about what you can’t do. Talk about what you can do.”

Image Credit: Jason Frank

How can this apply outside baseball? Ask Chris Dalzell.

He’s the owner of Shoreline Construction, which builds residential houses in the South Carolina Lowcountry. His customers are mostly high-net-worth people looking for second and third homes. After 13 years in business, Dalzell was doing fine, but he had a problem: “A lot of guys in town can produce the same product I can,” he says. To stay alive, he’s had to spend a lot of money on marketing. He’d long wondered how to distinguish himself from his competitors.

Then in 2017, Dalzell met Cole at an event. He was so taken with the Bananas’ story that he later drove to Savannah for a Fans First Experience workshop, a one-and-a-half-day program that Cole recently started to teach CEOs how to turn customers into fans for life. While there, they broke down Dalzell’s business by asking a version of the question Cole once asked himself: What do home buyers hate about building a home?

This got Dalzell thinking about every stage of the process. He saw that all of it — from design to contract to construction to post-closing — contained some tedium, and was therefore an opportunity to impress and delight his customers. So to start, he and Cole focused on the closing experience. Typically, when construction is done, clients walk through their new house with the builder and look for mistakes. Dalzell now realized what a buzzkill that was, especially on a day that was supposed to be about new beginnings. So he reimagined it as a “day one celebration” — a performance with an actual red carpet, a ribbon cutting, champagne, and gifts from local businesses. There would be no walk-through. Dalzell would just tell clients to move in; if they encountered problems or were unhappy with something, they could call his office and his team would come back.

When Dalzell returned to his construction office, he realized that he had to reorient his team to think about the customer, not just the job. “The hardest part is getting them to see that we can turn [a skeptical customer around] if we continue to exceed his expectations,” he says.

To help, Dalzell adopted another of Cole’s guidelines: Give your staff autonomy and creative license so they feel a sense of ownership over their roles. (This is what Cole does at the Bananas. “We have zero policies,” Cole says. “We give them freedom, and we expect creativity.”) So Dalzell invited his team to come up with ideas to wow clients, and they did. For a particularly finicky customer, Shoreline sent flowers on his anniversary. For a couple flying in to view the progress on their new home, Shoreline picked them up from their hotel in a limo, then delivered them to the unfinished frame of their house…where a catered dinner waited inside.

Since running programs like this, Dalzell says, Shoreline has been able to cut its traditional marketing budget significantly. “Our leads are coming from our customers,” he says. “They’re saying, ‘You can’t believe what Shoreline did for us.’ ”

Fans go bananas for the Bananas (and its Banana Beer).

Image Credit: Jason Frank

Cole’s philosophy, fans first, is all about serving the customer. But he believes it helps a company internally as well. In fact, he believes it’s helped the Bananas players become better at baseball. He said this last year while speaking to a business management class at Georgia Southern University, and the professor, Curtis Sproul, was immediately skeptical. “What happens in movies, where you take the lovable losers and put them in a great environment and they beat the Yankees — that doesn’t happen in real life,” Sproul says.

So Sproul wanted to test it. He compared the on-base percentage, plus slugging percentage, for every player in the Coastal Plain League over three years. He also looked at how players performed in college, both before and after they played in the league. The results were clear: Bananas players were the only ones in the league whose scores, when averaged together, showed a demonstrable improvement each year. “I was shocked when I saw it,” says Sproul.

The results wouldn’t have shocked a Bananas fan, though. Since its debut in 2016, the team has won its division twice and the league championships once. This summer, it went 35 and 15.

“This is 100 percent making me a better player, [and] I’m pitching much better here than in college,” says Alex Degen, the dancing pitcher. “In school ball, I tend to get a lot more nervous.”

Theories vary on what’s causing this. “What else can it be than how they manage the team, create an atmosphere for the players, allow them to be more themselves?” says Sproul. But Tyler Gillum, the Bananas’ coach, thinks the team atmosphere helps players become more versatile; they “learn to go from moment to moment” — from entertaining to playing and back again — “without a loss of enthusiasm or focus,” he says. Maybe that directly translates into going from offense to defense.

Still, despite the surprise results, Sproul worries that Cole’s success isn’t easily replicable. “Changing culture doesn’t always work, and more often than not, organizational change fails,” he says. He believes Cole has been so successful in Savannah because he started from scratch. And truth be told, now that the Bananas culture is established, Cole is having trouble adding people to it. He recently hired a former cruise director to be the team’s director of fun, but the guy “was put off by our culture because he was trained with checks and balances,” Cole says. The new hire kept asking what he was allowed to do. “I said, ‘Anything,’ and he didn’t understand,” Cole says. Generally, he’s had more luck promoting from within, even if it means putting inexperienced employees into higher-level positions.

It also remains to be seen how sustainable a Bananas-style culture can be. In Gastonia, the fans-first philosophy fell apart when Cole left. He tried to train his replacement before selling the Grizzlies, but the organization lacked the necessary commitment and enthusiasm for his approach, and ticket sales declined.

Still, change like this can ripple out. Just look at the Coastal Plain League, where the Savannah Bananas play. Cole often describes himself as “the redheaded stepchild” of the organization, disdained by the tradition-minded owners of other teams. “They hate us; this is the truth,” he says. But Justin Sellers, the league’s COO and commissioner, doesn’t sound so fiery. Cole says the Bananas are all about entertainment, and Sellers agrees. “I’ve learned to go down the rabbit hole [with Cole],” Sellers says, “and reserve the right to say no later on.”

And the rest of the league has taken notice of Cole’s success. At least half the teams now offer all-you-can-eat tickets, encourage more player-fan interaction, and routinely inject humor into the proceedings. One of the league’s newest teams, founded in Macon, Ga., in 2018, even named itself the Macon Bacon. Sure, things like this may break with tradition. They may not be what baseball stadiums were intended for in the 1920s. But when tradition is bucked and it leads to profit, then tradition stops looking so important. Instead, it becomes an opportunity for leaders to look at their customers anew — and start to give them what they never knew they wanted

https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/341830