Know your worth when pricing your work with advice from the AOI and top illustrators Tom Humberstone and Miss Magpie Fashion Spy.

Out of the many findings from Ben O’Brien’s latest Annual Illustrator’s Survey, one that stuck out was the finding that almost 60% of creatives are not confident when estimating fees for clients.

Valuing one’s work in monetary terms is a rites-of-passage for many illustrators, and often the first major stumbling block when embarking on a full-time career in art and illustration.

This year’s announcement that the Association of Illustrators (AOI) was forced to drop its price assistance service caused some debate in the art world, but overlooked in discussions was the fact that creatives are better served in getting street smart about their worth instead of simply being spoonfed figures. Calculating the fee an illustrator should expect is never an exact science, relying on a number of variables which we’ll explore in this advice piece on pricing your work as an illustrator.

For this feature we reached out to AOI membership manager Lou Bones in light of the organisation’s newly-launched campaign to get members more salary-savvy, drawing on her and the Association’s extensive expertise negotiating contracts for illustrators around the world.

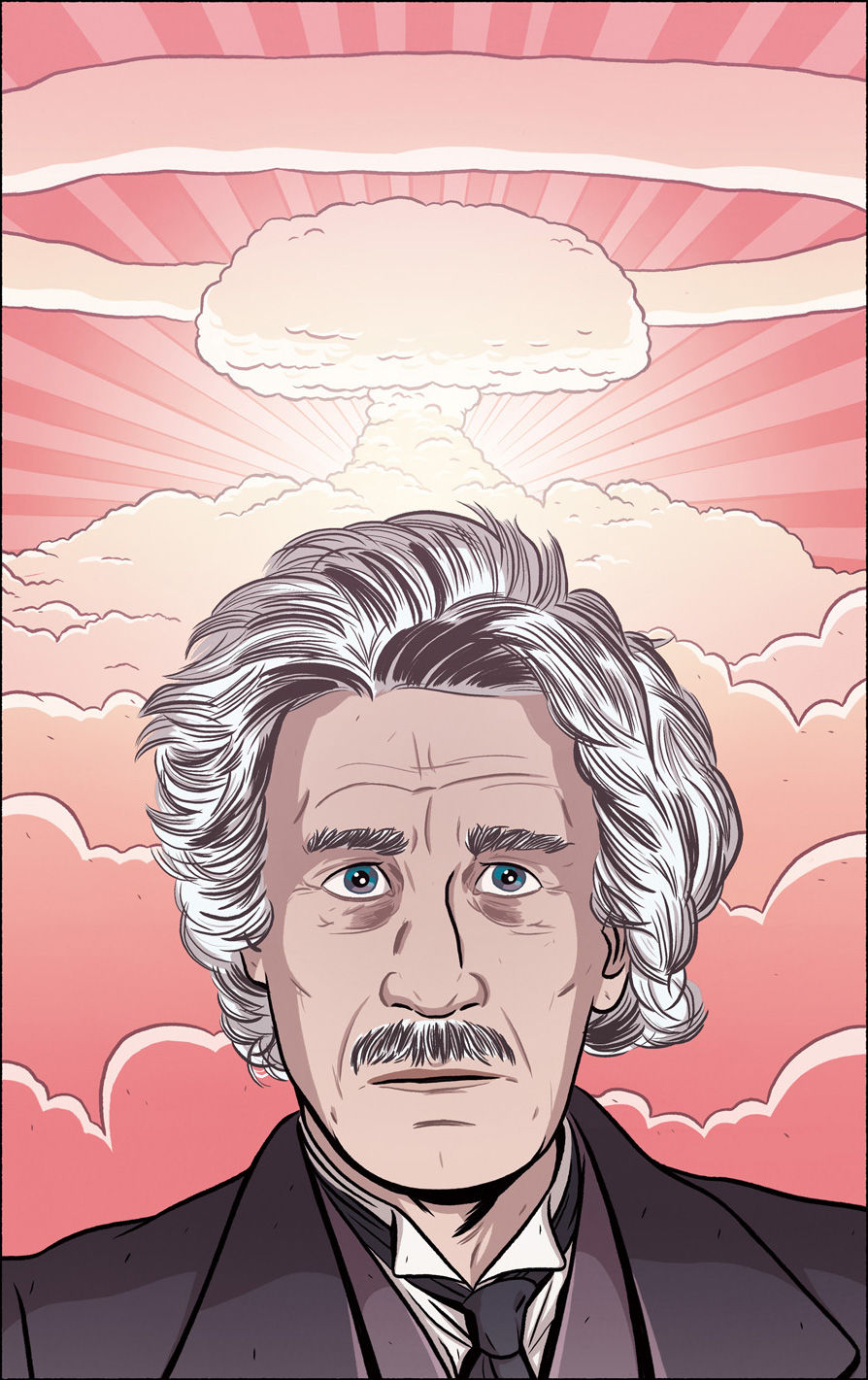

We’ve also spoken to some of those illustrators, chatting with creatives like editorial/book cover artist Tom Humberstone – who’s provided us the brilliant illustration heading this feature – and fashion illustrator Niki Groom aka Miss Magpie Fashion Spy, whose extensive experience in creating for different mediums has led both to be dab hands at negotiating with clients.

Zero sum = zero.

As an artist in her own right, the AOI’s Lou Bones knows the feeling of being ‘grateful’ of being paid to create. She also knows the perils of such thinking.

“You’re blessed that you’re doing something that you love and that leads directly into being grateful,” she explains passionately as we chat in Somerset House, home to AOI HQ. “”I’m grateful that you’re going to pay me for a drawing‘, for example. But at the end of the day you’ve chosen a career. You’ve invested time, effort and money into your career and you should be be paid properly – and if you’re starting out, then you should expect a starting salary.

“That’s what you should be aiming at – a baseline salary regardless of what your route into illustration was,” she continues. “If you’re not getting that or being offered it, then you need to look elsewhere.

“If you’re just working job to job, fee to fee, then it’s not going to work. Keep the bigger picture in mind, and know that the fee you charge for a job is dependent on how many jobs you have that year and how flush – or not flush – you currently are.”

The quote is key – never work for free. Digital Arts believes illustrators shouldn’t be grateful for the opportunity to gain ‘exposure’ by working for no fee, as over three quarters of respondents in the Illustrator’s Survey revealed themselves to be guilty of. Also be wary of design competitions, especially ones run by brands who’ll use your work without paying for the privilege.

Size up your client (they’ll be doing the same)

When discussing quotes with illustrators, Lou has a number one rule.

“You need to establish the size of the client and the stipulations of the license,” she says.”The stipulations of the license are going to be where the clients wants to use the information, how long they want to use the information – and exactly at what scale and what use they want to use the information for.”

“A local, regional client is obviously going to have a smaller budget and you know where you’re at in terms of your parameters, whereas a global client may want to use the license only in the UK instead of worldwide. This is how you start to hone down where you are in terms of the price scope.

“There are also ‘soft’ considerations when knowing your value in negotiations,” Lou reminds us. “For example, maybe you have a very large social media reach. Is the client buying into your social media reach and audience as well as their own audience?”

We asked Niki Groom, a fashion illustrator with a large Twitter and Instagram following as @miss_magpie_spy, on how to take into account their social audience during negotiations, being wary of how a brand can not only be buying into your talent, but also your popularity.

“I view both things separately,” she tells us. “If I’m being commissioned to create something for a brand and the usage doesn’t mention me sharing it anywhere then there’s a chance I won’t want to share it anyway – I don’t publicly share all of the work I do.

“But if a brand requires for me to post the image on my social media,” Niki continues, “then I will charge for this separately and again will be clear in the agreement as to what is covered (eg 3 x Instagram Story, 1 x grid post, timelines etc).

“I will also clarify with them whether I am tagged as the artist in their Instagram posts etc. I will also make it clear on Instagram when I’m sharing work that a client has paid for me to feature, inline with the Advertising Standards Agency.”

Advice on advertising

On the topic of social, if you’re ever asked to create a social media campaign, then treat it like any other advertising campaign – and expect it to be more lucrative than any other kind of illustration gig.

“There’s two different kinds of advertising – above the line (ATL) and below the line (BTL),” explains Lou.

“ATL is paid for advertising. So an ad in a magazine or on a billboard, a digital banner ad, even a print that markets a new film remake or sequel to a built-in audience by being based on the original cult movie.

“Then there’s BTL, which is non-paid for digital or printed promotional material. So it could be an Instagram post, a banner or an image on a website. It could be staff uniforms or point of sale, so promotional stuff in the client’s store which they own. It could be leaflets, flyers, newsletters, internal documents. These are all below the line.

“ATL is paid for to reach a larger audience online or in real life, so illustrators should know that increases the fee.

“You’ve also got to think about super big sites like Piccadilly Circus or billboards at Heathrow. They would be almost the same fee as a whole campaign simply because of the location.

“It also depends on duration,” Lou continues. “A lot of those sites have digital ads now rather than printed ones, so your digital campaign might only be up there for a week – but a printed billboard might be up there for a month or half a year, so you can quote your client for more.

“Illustrators have also got to factor in illustrations being used in a TV/streaming ad, or a cinema commercial. Both are above the line advertising, so you’re talking about a lot of money as payment.”

In the same way you size up your client, you should also size up the scale of the campaign, Lou says. Don’t assume that because something is made for the cinema, your fee will be automatically among the highest scales seen in ATL advertising.

“Is the ad going to be in an independent cinema or a few? Or is it going to be in Cineworlds across the UK? Your client should specify this, but if not, you need to find out if you want to be paid fairly,” Lou concludes.

Pointers on packaging

If you’re designing a label or packaging for a brand, then don’t undercharge, especially for a rebranding or a brand new product.

“It costs a lot of money to make a product, and the license involved is always longer than one for advertising,” Lou points out.

“Generally a normal medium to large size business will mean a three or five year license for the product. And bigger clients who might ask you to package a staple in their range will mean a perpetual license, which is forever – same for when you’re designing a logo.”

There are also opportunities for illustrators to make limited edition packaging for brands; while licenses are shorter in this arena, there’s still money to be made, as Niki Groom confirms.

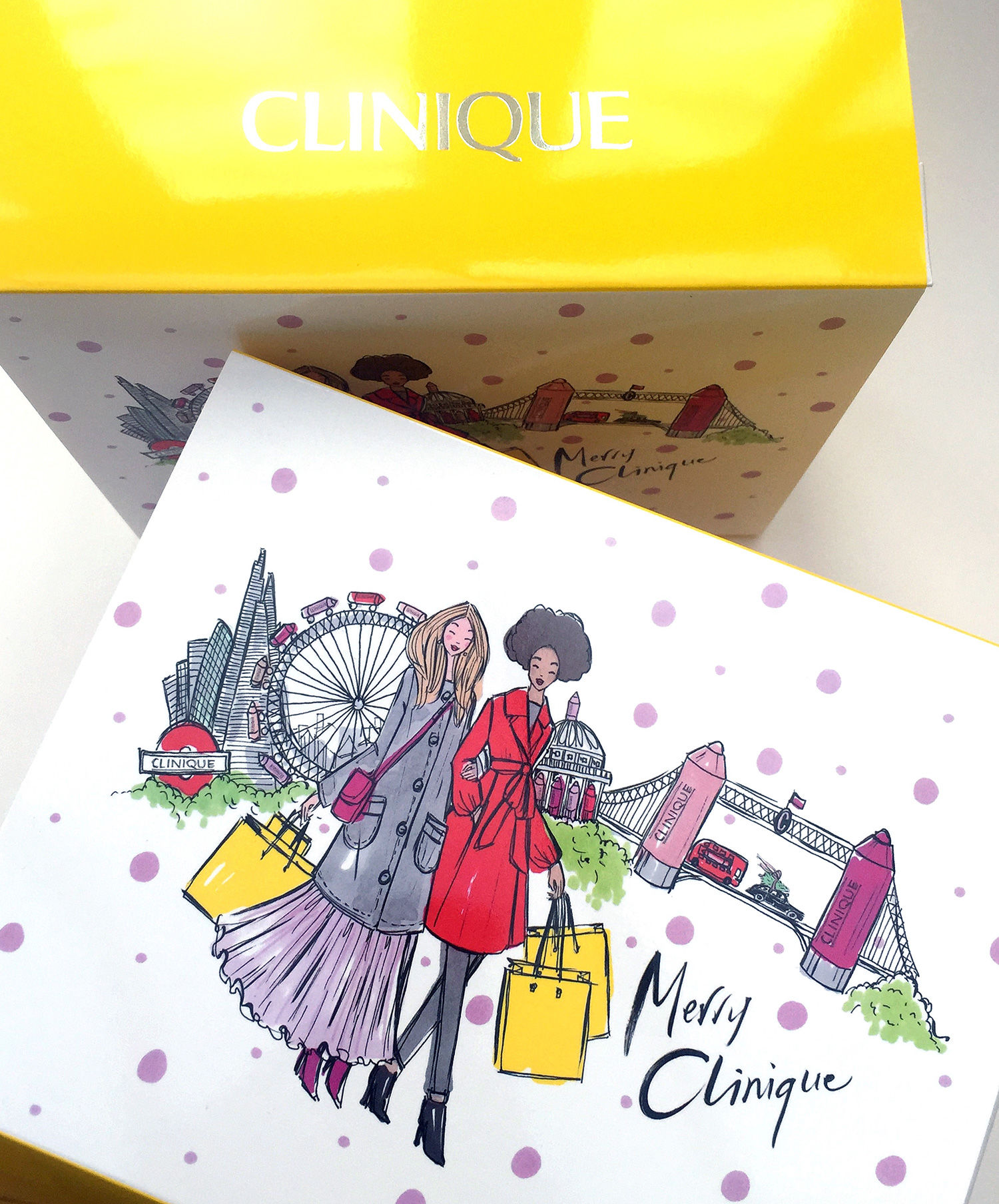

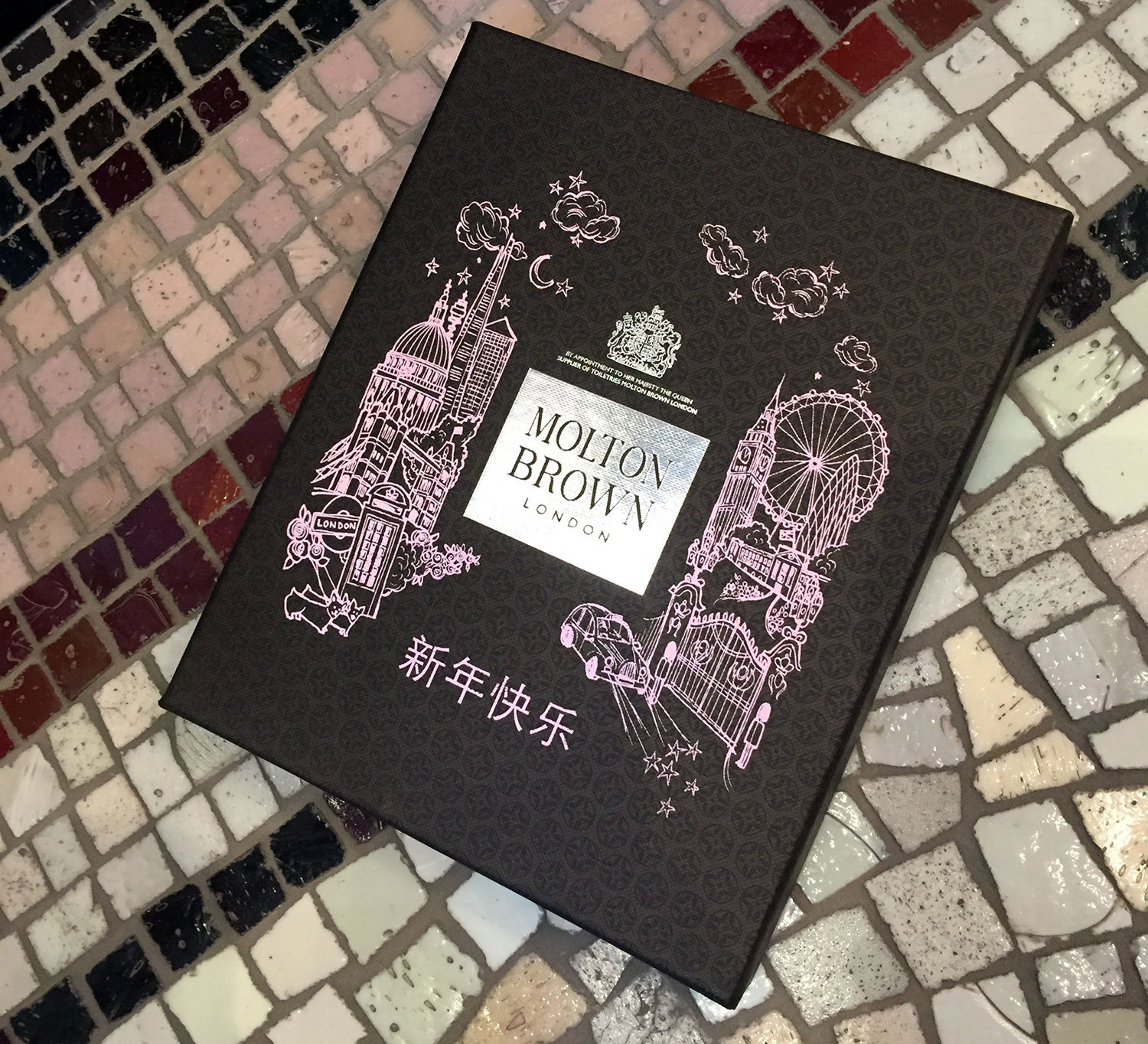

“I’m seeing an increase in the amount of packaging commissions I’m getting for limited edition projects,” she tells Digital Arts. “My main clients in this area are Clinique and Molton Brown (latter pictured below).

“It’s important to really understand the reach of these projects; for example I worked with Clinique on a box that was exclusively sold in John Lewis Oxford Street at the end of last year to encourage Christmas sales.

“It was for a short window of time and in one store. Had it been licensed for the whole UK the price would have been higher, and if it was available all year round again the price would change. It’s really important therefore to understand licensing when dealing with projects like this.”

Interestingly, Niki points out that even if an established product has been singled out as worthy of your customisation, that doesn’t mean the ad campaign is ready-made and built in your image, giving you another possible gig to work on.

“From my experience the commission for limited edition pieces comes after the advertising campaign is decided,” she explains. “There’s a theme and a mood board that communicates the top line ideas for the campaign, and often these will come from the marketing department, whereas I might be in touch with the retail or events department instead.

“But if I were to be creating packaging for a brand on a more global level and it were to be part of the campaign imagery then again the price quoted would reflect this.”

Big box, little box – go fish?

“I have only done one packaging job that was for a much smaller client, a start up that never got off the ground sadly,” Niki reveals, before confirming Lou’s advice that it’s important to quote based on the size of the company.

“The price was lower for them as they weren’t a big brand. Still, saying that, there are many jobs I don’t accept due to the budget not being enough. A start-up should have good budget if they want bespoke illustration, otherwise they should be using stock photography (or drawing the artwork themselves).”

No matter the size of your client, Niki advises to keep all negotiations clear and in writing.

“I don’t discuss costs verbally,” she says. “I keep negotiation emails friendly but formal; they are not the place for any emotion or long explanations. It’s enough to say your quote is in line with industry standard.”

“If a client then says they don’t have the budget for what they are asking for but you are really keen to work with them then offer suggestions.

“For example, do they really need the license for three years or could it be one? Could you adapt your style to meet the budget? Do they really need a worldwide license – or could it just be UK-based?”

Niki applies this philosophy to all commissions, for example live art sessions. The artist does this by offering to spend, say, one or two hours in a store instead of longer should a brand’s budget be small. In other words, it’s all about all parties involved meeting halfway.

Book Money

Think books are a dying market with equally as moribund fees for cover designs? Think again.

“Children’s book publishing is absolutely some stellar couple of years,” says Lou, with more and more kid lit illustrators coming to the AOI for contractual help.

“What we deal with at the AOI is illustrators illustrating a full book or that they are author-illustrator. This is generally going to take you three to six months of the year and that’s the kind of fee that you need to be remunerated and to cover you at least for that time.”

On top of the fee illustrators should also ensure they receive royalties from book sales – as standard – along with an advance (note that in most cases royalties will only be paid once the book’s earned back its advance).

“If you’re not benefiting from the royalties you need to take that into consideration in your advance as well,” Lou says. “So if you know that book is going be really successful but the publisher is offering you a flat fee, then you need to pump up the quote.”

“In terms of illustrators figuring out how they arrive at advance fees, again it’s about how much money illustrators want to make in a year. A book is the most amount of work an illustrator will do. How many can you make? Are you going to be working on them all at the same time?

“That’s how you start to think about what your advance is because it needs to cover you,” Lou points out. “It needs to cover your rent, or any scenario – eg your laptop dying and you losing all your work. And if the publisher’s a repeat customer because you’ve been so successful in the past, then factor that into the fee too.”

“If you’re lucky you might even get asked to do different covers for different areas of the world which means you quote another fee – simple as that.”

One illustrator who has had both experience as book cover artist and author-illustrator of his own work is Tom Humberstone, his distinctive comic book style seen on covers for graphic novels and biographies of Einstein. Speaking with Digital Arts, Tom advises a close reading of the contract and making sure you’re clear on the terms of the agreement from the start.

“Ask friends/peers if they’ve worked with the publisher before to find out if you’ll be asked to make changes you’re uncomfortable with, or if the editors are difficult to work with. Sometimes, you might not be in a position to say no to a big book gig despite some terms you’re not happy with. If so, just make sure you’re entering into the contract with your eyes wide open.” Tom says.

“It may be guaranteed, well-paid work for a few months, but make sure it’s worth it as it will be the dominant aspect of your life for a large portion of the year.”

Enlightenment on editorial

Tom’s extensive experience in artwork for big names like the BBC and The Guardian mean’s he’s also an authority on editorial illustration.

“The key in quoting fees for editorial work is to have a rough idea about how long the work will take and have an ideal daily/hourly rate in mind and work from there,” Tom advises. “Try to be realistic about what size of fee is available and what your time is worth. If the fee for a small spot illustration is half your daily rate – only take it on if you think you can produce it (to a standard you’re happy with) within that timeframe.

“Often, these sort of commissions rely on the professional pride and perfectionism of the artist to work extra hours regardless of the fee,” he explains. “Try to fight that instinct if you can. You want to create sustainable expectations with your work based on the time/budget available so you can avoid burnout.”

While Digital Arts is aware through its relationships with illustrators over the years that this is a field less lucrative than advertising, packaging and books – think hundreds instead of thousands for a gig, unless you’re designing for a mag cover – there is still money to be made as long as you don’t undersell yourself.

“If possible, stick to your guns,” is Tom’s final piece of advice. “I appreciate it’s not always possible and some months are quieter than others so the temptation to take lower paid work can be strong. My rule of thumb is to only do so if the work looks really fun and it’s clear the client doesn’t have a huge budget (sadly, these two things are often linked).

“If the work looks like the exact opposite of fun, charge three or four times as much as you normally would. If you don’t get the commission, it’s no big loss – but if you do, at least the pay is good.”

https://www.digitalartsonline.co.uk/features/creative-business/how-to-price-illustrations/