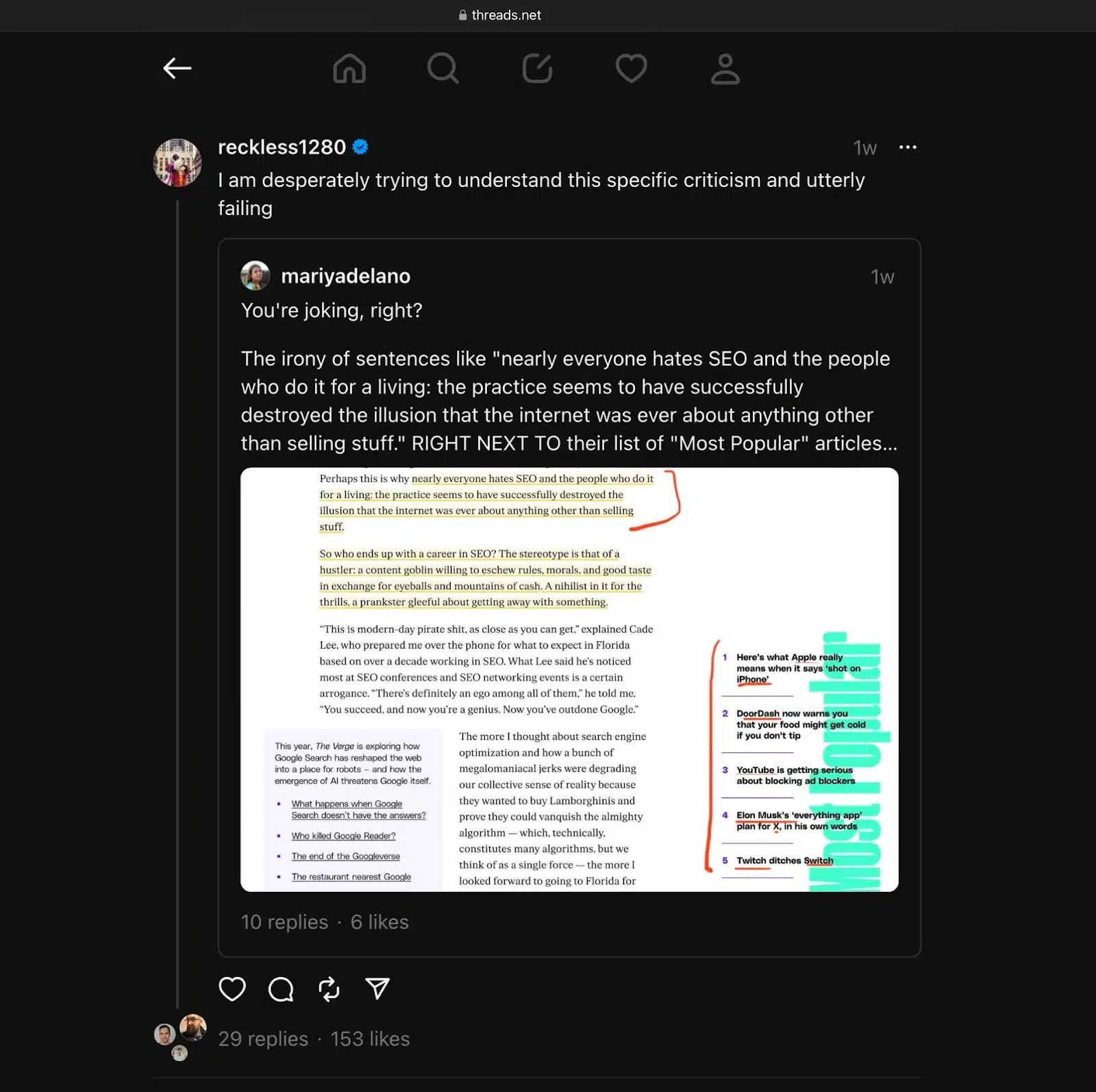

When The Verge published “The people who ruined the internet” on Nov. 1, it caused a shockwave across the search engine optimization (SEO) world. Their writer, Amanda Chicago Lewis, described us in a particularly unflattering way:

- “So who ends up with a career in SEO? The stereotype is that of a hustler: a content goblin willing to eschew rules, morals, and good taste in exchange for eyeballs and mountains of cash. A nihilist in it for the thrills, a prankster gleeful about getting away with something.”

As you might be able to guess, calling people “content goblins” doesn’t tend to make them feel particularly great. So, predictably, the article did what it seemed designed to do: The Verge made many search marketers angry, including me.

While this is another response piece, I won’t be repeating the claims made before me. If you’d like to catch up on this story, you can find some other notable replies here:

Instead, I’d like us to use The Verge as a jumping-off point. I’ll show you why I consider their piece problematic, describe the impact it’s had on us in SEO, and then zoom out to what I see as the more interesting conversation:

Who, if anyone, “ruined the internet” and how did it get us where we are now?

Buckle up. It’s going to be a long ride.

Why we care

Here’s my larger point: the Verge article correctly pointed out a problem. The web, as it exists today, is in trouble. Things are falling apart. Something needs to change.

However, the Verge didn’t point their finger in the right direction. Instead, I propose a more complex explanation – the web is stuck in a “sucker’s choice” created by the advertising and publishing status quo.

Everyone who wants to make a living online seems to feel trapped between two terrible options:

- Spam and force your way into getting people to pay attention and buy from you.

- Give up on ever making money, sharing your work with others, or promoting your products or services.

But I believe that by properly examining the problem that The Verge pointed out, we can figure out how not to resort to extremes of silence or violence.

Marketers, journalists and users – it’s time for us to have a crucial conversation about the web, why it broke and how we can fix it.

What happened

At first, I didn’t want to write this piece.

I don’t think I’m the most qualified person to do so. I’ve only been in marketing for four years.

I’m not a journalist, and I existed on the 2000s internet exclusively confined to Ukrainian- and Russian-language forums about the Sims, MMORPGs, and Winx Club. I haven’t lived the history of SEO or the larger internet the way most of you reading this probably have.

But I feel a deep sense of obligation to do this topic justice. Because so far, many of the people I would have assumed to be more qualified have messed it up. At best, major journalists and publications have been treating the field of SEO as some strange middle-school drama and, at worst, as a shadowy internet mafia.

I’m disappointed in how much The Verge’s editor-in-chief, Nilay Patel, has gleefully indulged in celebrating and mocking every bit of anger that their article caused in our community.

Above all, I’m disappointed by how little people like Patel are interested in talking to the people they’re supposedly studying – SEOs and marketers like me or those of you who frequent Search Engine Land.

Voyeuristic coverage like this stinks of tabloids, yet Business Insider also decided to jump aboard, painting the whole affair as salacious suburban gossip:

- “I never thought I’d say these words, but, friends: The SEO drama is spicy.”

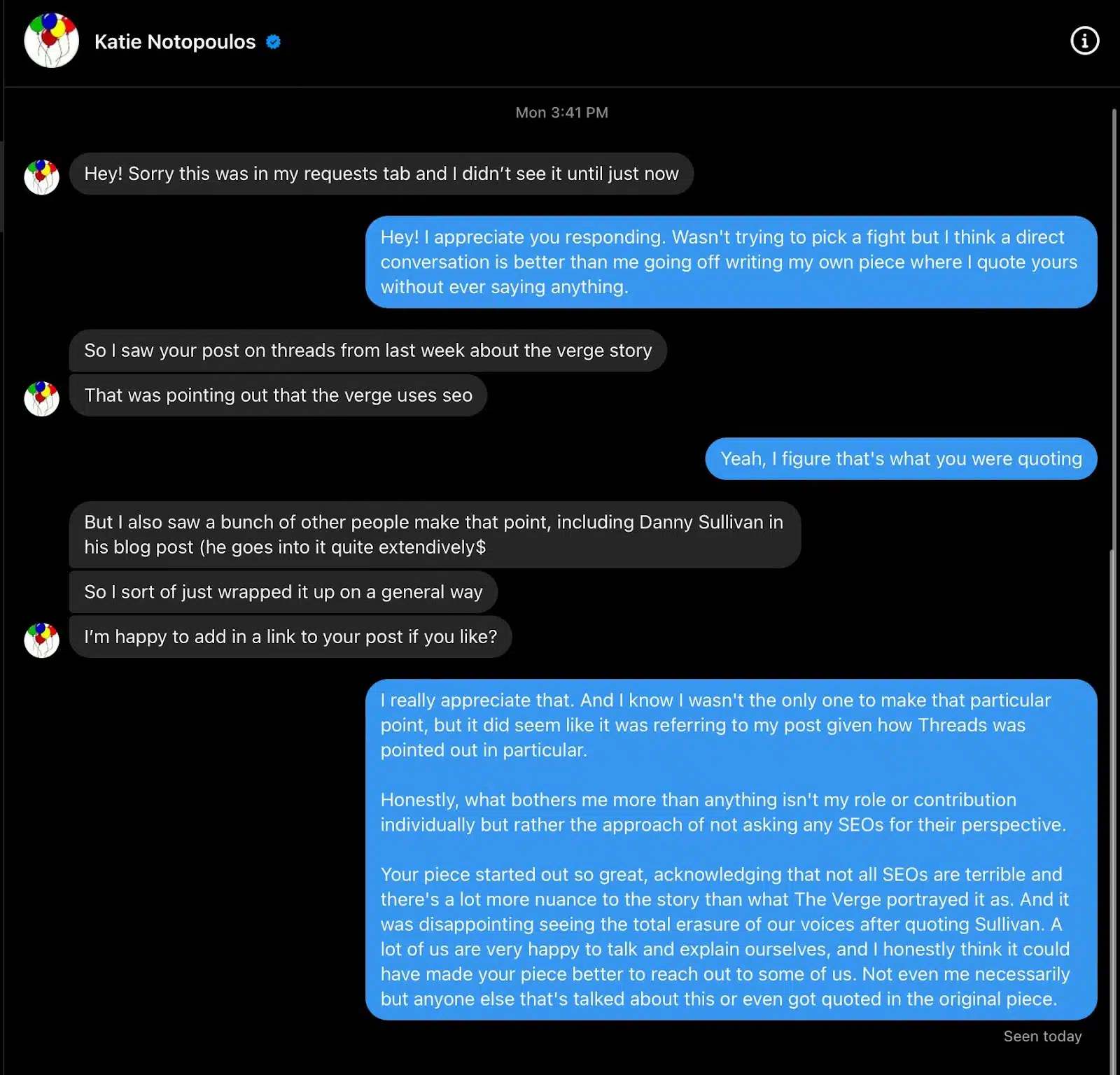

It seems that Insider’s writer, Katie Notopoulos, shared The Verge’s mindset. Talking about The Verge’s piece on his podcast, Patel stated:

- “The funniest thing about this whole situation is the SEO professionals being mad at us but doing perfect SEO by instinct, and all the places where they’re yelling at us. Chef’s kiss.”

Patel’s eagerness to drum up strife prompted me to examine whether he has some long-standing grudge against the SEO profession.

I discovered that he graduated from the same law school in the same year as my mother’s ex-boyfriend. But, disappointingly, when I asked that ex-boyfriend about it, he said he didn’t have any recollection of Patel whatsoever.

I understand why our angry reactions are so compelling. Much like I’m disappointed that I couldn’t dig up any fun stories about Patel’s law school years, The Verge seems upset at how devoid of drama the SEO industry truly is.

The boring reality of ‘SEO subculture’

Patel claims that The Verge’s recent piece is about “the culture of the people who practice it professionally.” Well, if that was the intent with which Chicago Lewis was sent on assignment, no wonder they felt compelled to manufacture outrage.

After all, SEO, as a “subculture,” is actually really boring. We don’t even have alligators, despite The Verge’s claims:

- “I’ve yet to see one alligator – though, full disclosure, I once saw Danny Sullivan and Matt Cutts toss out plush penguins to the audience at an SMX Advanced keynote in Seattle,” recalled Goodwin, managing editor of Search Engine Land and SMX.

Plush penguins sound absolutely adorable. But they are a far cry from the supposed antics of “megalomaniacal jerks [who] were degrading our collective sense of reality because they wanted to buy Lamborghinis” that Chicago Lewis wrote about.

We aren’t even particularly rich. Our collective economic status is woefully unremarkable. As Tommy Walker, founder of The Content Studio, explained:

- “The majority are struggling or ‘middle class; SEOs doing what they can and just get by.”

I know it’s easy to think that we’re all rich and successful. That would be so much more “spicy.” And third-party estimates can certainly give you that impression. For instance, this email-scraping website thinks that my agency’s revenue is somewhere between $1 million and 5 million.

As much as I wish that number were true, the reality of running a boutique marketing agency in its second year is much less exciting.

So, if we aren’t millionaires hanging out with alligators, who are we? What does this “subculture” of SEOs really look like?

We are a profession of people with a similar skillset: doing tasks around helping websites show up on search engines like Google or Bing. That’s… it.

Sure, like any specialized field, people in SEO tend to talk to each other. As described by Duane Forrester, vice president of industry insights at Yext:

- “The SEO community is tight-knit and supportive – everyone started as random usernames in forums, then built friendships over years of attending conferences and tackling problems together.“

We do talk to other people in our field. And, controversially, sometimes we even like those people enough to hang out together!

I understand that SEO seems mysterious. After all, we help others become visible online. But ourselves, we’re more hidden.

- “We’re a somewhat in-the-background industry that employs thousands of people,” Forrester said.

The Verge claimed they wanted to bring our field out of the shadows and into the spotlight. So, let’s do exactly that.

I’d like to start by introducing you to the people that The Verge left out.

To that end, I’ve interviewed 17 SEO and marketing professionals, all appearing in this piece.

I’ve also created a public gallery to feature some of the wonderful people who make up SEO and celebrate how they work to improve our field and the web. You can browse through the gallery here, and nominate other SEOs using this form.

The voices they left out

Both The Verge and Insider argued that they wished to expose the people in SEO to the public. But if you read their pieces, you’ll notice a curious absence.

Most SEOs are nowhere to be seen. Neither Chicago Lewis nor Notopoulos inquire about the different subgroups of our industry, the organizations and communities within it, the events that we run and attend, or our relationships with others in our field and other professions.

As Lily Ray, head of organic research at Amsive Digital (and one of the people quoted in The Verge’s piece), told me:

- “The article didn’t share enough about the work of real, modern-day SEOs, whose commentary would have painted a much more clear picture.”

It doesn’t make sense. Why not just ask us what we think?

Although our work is often behind the scenes, we are easy to find as people. Many of us love media features and actively seek out exposure. We are right there, ready to share our opinions and expertise.

But when I tried to engage Notopoulos on this exact question, she offered me a link and then left me on “seen.”

Perhaps if these journalists listened to us, they might have discovered voices that didn’t fit into their neat narrative. People like Walker, who are riddled with self-doubt as to the impact of their own work:

- “Is it us that’s ruining the internet, or is it Google that’s ruining us? I think we’ve all been asking that for a while, so then having that reflected back at us, called content goblins, and painted as riding around in Ferraris making money hand over fist, had most of us feeling bewildered and hurt.”

I’m neither a full-time journalist nor an expert on journalistic responsibility, but I am a public-facing writer and creator. And I know that when you’re trusted to represent other people’s stories, you must handle them with care and empathy because real people feel really hurt when their words are twisted and misrepresented for somebody else’s gain.

So, if journalists with years of experience and big budgets won’t do our story justice – I’ll do it.

Armed with my 25 years of being a human on this planet, a generous network of people who offered up their words for this piece, a byline in this “trade rag,” and only two weeks of time – here’s what I managed to put together. I hope I’ve managed to give voice to those of you who felt erased from the other coverage.

At the end of the day, this story isn’t about me. It’s about you – the person reading this piece. It’s about your relationship to the internet, the media you consume, and the people who make it happen.

Let’s see why it’s all such a mess.

How we can find a way out

When we feel hurt and helpless, it’s easy to point fingers.

If we can blame our pain on somebody else, then we don’t have to do the difficult work of looking into how we might have contributed to perpetuating our own suffering. We can simply find a scapegoat and pin all responsibility for fixing the mess on them.

I don’t blame the Verge for falling into this trap. When they see us (SEOs), they see the people who work explicitly helping businesses make money online. And they see our role in commercializing the web all too clearly, while missing the other parties who may have also played a part:

- “Google isn’t perfect. And neither are the people or the brands that write content getting found on Google,” says Nikki Lam, senior director of SEO at NP Digital.

But why are we looking for anyone else to blame?

Fighting with each other won’t help us improve anything. So, to find a solution, I’d like to reframe the question that The Verge asked in their title.

Instead of trying to point fingers at who ruined the internet, let’s diagnose the problem by asking:

- What did “ruining the internet” mean?

- How can we improve the internet going forward?

How to make money on the internet: The origins of spam

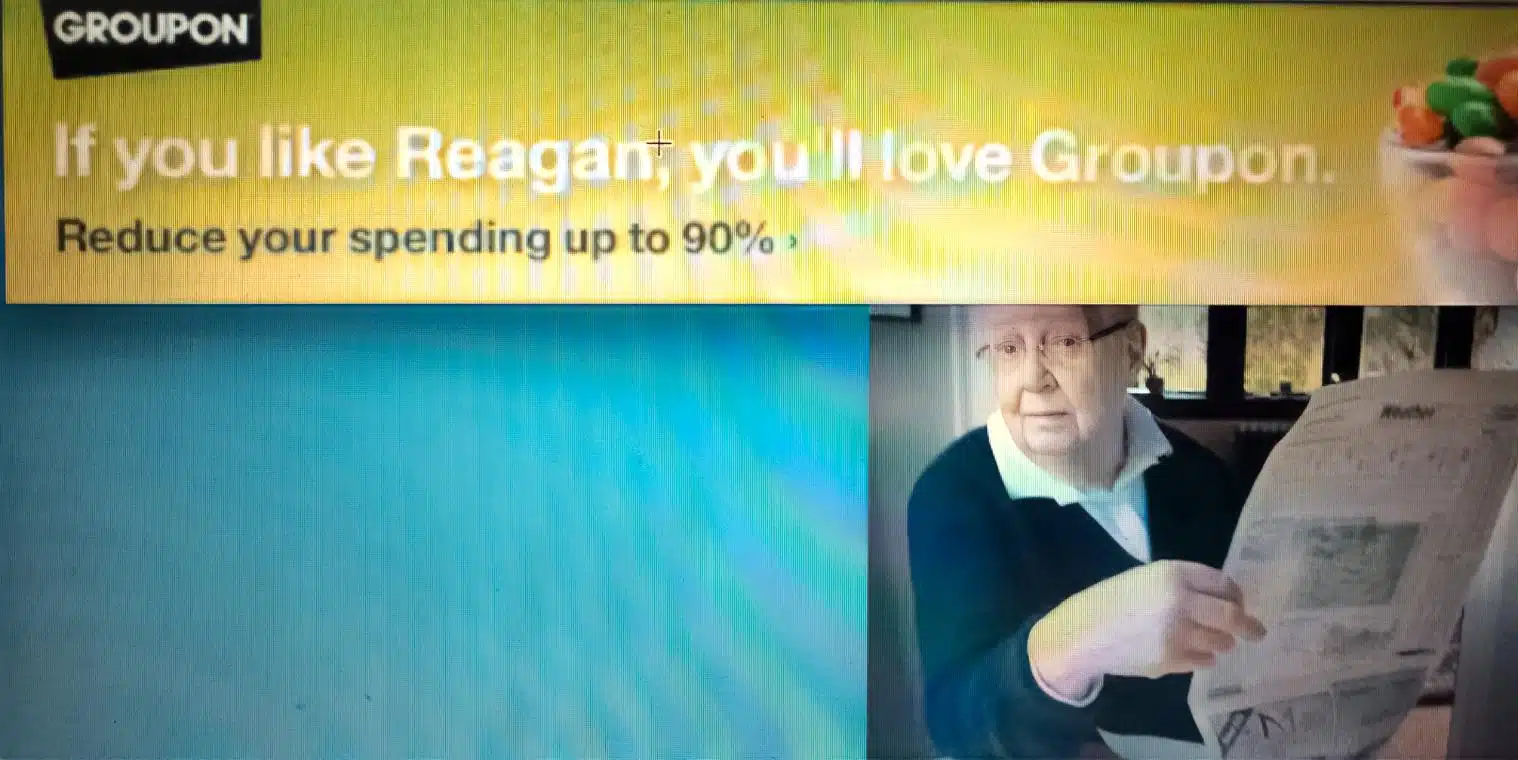

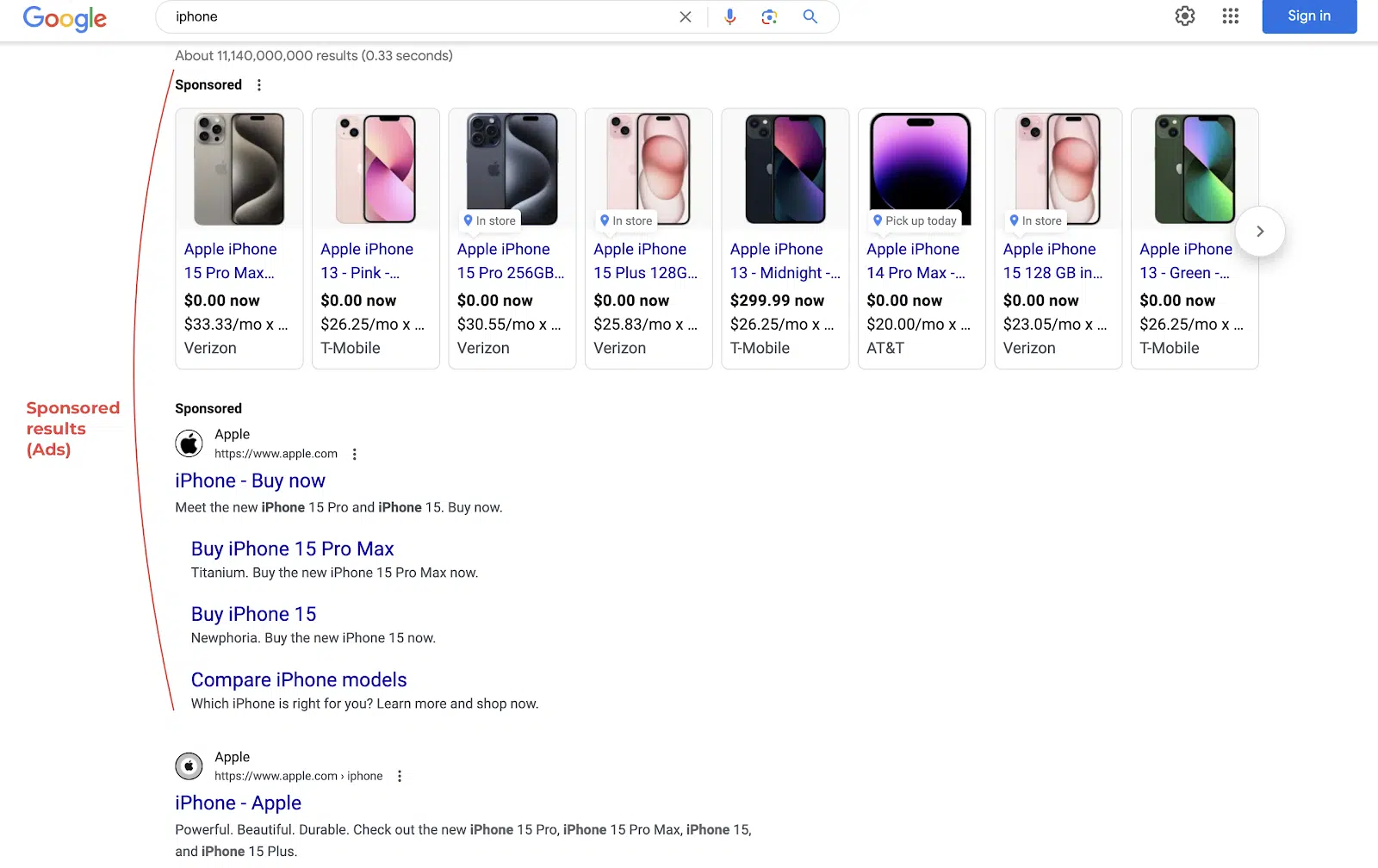

If you want to understand the web today, you need to think about this image:

This is an old ad from Fox News that was shared with me by Mastodon user HunterNP. An ecommerce platform for finding deals and promo codes is advertising on a conservative news site with a banner ad that:

- Shows an old white man reading a newspaper, representing the type of person who they think would go on Fox News.

- Takes up a lot of space on the page and catches enough attention that someone took a screenshot of it and remembered it for years.

- Promotes the company’s value proposition of saving money.

- Targets the presumed interest of a Fox News visitor – conservative politics and a fondness for a figure like Ronald Reagan.

All of this feels obvious.

Right now, you’re probably wondering why I’d point your attention to an archaic ad in an article about SEO. But your confusion is the point: we have been missing something that’s been hiding in plain sight this entire time.

Chicago Lewis explains her distaste for SEO because “the practice seems to have successfully destroyed the illusion that the internet was ever about anything other than selling stuff.”

But that complaint is much larger in scope than search engine optimization. If “ruining the internet” means turning it into a place for “selling stuff,” then we need to consider online ads, user targeting, and the very practice of digital marketing.

Why was Groupon advertising on Fox News? And why do businesses promote themselves online?

What’s the point of SEO?

Ray told me that “the goal of most SEOs is not simply to make as much money as possible while recklessly ‘ruining the internet.’”

But SEOs are in the business of helping companies sell things, right?

Before truly addressing why the web is filled with marketing, we need to understand what SEO and marketing are. (I expect people outside Search Engine Land’s typical audience to read this piece, so feel free to skip this section if you are already in the field.)

Chicago Lewis displayed a certain level of ignorance about our field. She may have talked to marketers, but she didn’t truly figure out what our jobs are for. I’m not saying this to criticize her. Chicago Lewis is in good company:

- “Really, the average person doesn’t understand what we do. ‘SEO? What’s that?’ Ten minutes later, blank stares. Or the subject has already changed.” – Goodwin said.

Marketing is not well understood in popular culture. And SEO, as a technical and obscure subset of marketing, seems even more confusing. After all, why would you need to optimize anything for Google? As Eric Enge, president at Pilot Holding, told me:

- “Many assume that all you need to do is publish your website and then you’re done. But that’s not true.”

We frequently work with businesses who don’t know why they might need our help. They believe that as long as their website has some kind of design, a couple pages, and information about their company or a topic – that’s all they need to get found by others.

But search engines don’t work that way.

You might have the best business in the world, but if your site doesn’t account for how users look things up or how services like Google categorize websites, you won’t appear at the top of a search engine results page (SERP).

Professionals like Enge view their job as a way to “help dispel myths about SEO and help organizations understand what they need to succeed.” And helping organizations succeed comes down to two types of tasks:

- Content optimization: Creating and assisting with creation of pages that might provide information, entertainment, or other value to site visitors.

- Technical optimization: Ensuring that sites load well, are correctly parsed by search engines, and provide a good user experience.

This separation is the source of a common misunderstanding: many SEOs never even touch content. I happen to be a content specialist, but there are search marketers who work purely with web development, UX and accessibility.

- “We often work hand in hand with website accessibility specialists, who ensure content is accessible to users with disabilities because we often share the same goals,” Ray said.

How are these two parts of SEO connected? By chasing the same goal as all of marketing – helping the right messages reach the right people. And online, that means:

- “A ‘good’ internet experience is one that allows users to easily access the information they’re looking for, in a reliable way,” said Aleyda Solís, international SEO consultant and founder at Orainti.

If you think of the internet as an organism, you could describe it as I have in another piece:

- “Its bloodstream is the flow of all the content that the users produce over the days, months, and years. Its pulse is the meaning created from those spontaneous connections and ideas. Its beating heart is a synthesis of all the people who live out sections of their lives on its pages.”

And what role do marketers play in this system?

We are the red blood cells, messengers carrying all that content and the meaning humans create from one website or social account to another.

We are the agents who help disparate organs of the web to connect, forming the large integrated organism that we call “the internet.”

What is spam, really?

So, if marketers are the messengers enabling communication between different parts of the web, how can we also be a source of the toxic sludge ruining it?

The Verge claims that marketers are “clogging the internet with bullshit.” Or, in less graphic detail – that in chasing financial returns for businesses, we are creating spam.

But many of us see that conflation as a misunderstanding. After all, if we are clogging the veins and arteries we move through, we are no longer enabling good communication.

- “Showcasing doing SEO as being equal to spamming is like saying all journalism is writing clickbait fluff or fake news. No, it’s not. Most SEOs out there are doing fantastic work helping businesses to connect with clients through search, to better satisfy their needs,” Solís said.

We can’t call marketing content spam until we know what “spam” even is. So I’ve asked my Mastodon followers to share some examples of encountering online spam from the earlier days, preferably pre-2005. I hoped that in distancing these examples from our current moment we would have an easier time defining what turns them into “spam”.

One of the responses was from Paul Bissex, who sent me this post he wrote back in 1997, titled “Second Thoughts on Spam”:

“So far today I have received 16 new pieces of e-mail. Eight of them are the usual — items from discussion lists, messages from friends. The other eight are also the usual, unfortunately. They’re what’s known as “spam”: junk e-mail.The official term is “unsolicited commercial e-mail.” For those lucky readers unfamiliar with it, these messages are generally cheesy, repetitive, ungrammatical sales pitches. “ARE YOU LOOKING FOR A WAY TO DRAMATICALLY INCREASE YOUR BUSINESS OR START ONE?” asks the first spam message in my in-box. “AMAZING international calling rates,” boasts the next. These are typical. Quick money. Lots of capital letters.”

Another response came from Edward Vielmetti, who was quoted in a 1994 story about online advertising by The New York Times. The piece describes the controversy around a company that wished to create ad-specific “zones” on Usenet. Placing ads on the network:

“[W]hile not illegal, violated long-held traditions against random placement of any type of messages on news groups. Such scatter-shot messaging is known as ‘spamming’,” Peter H. Lewis writing for The New York Times (1994).

However, not everyone felt that any presence of commercial promotion online would count as spam. My commenter, Vielmetti, was quoted saying that advertising groups appeared “spontaneously and organically” around “existing discussion groups with a ready audience. That appears to work phenomenally well.”

So, what can we learn from these early references to spam and online marketing? I would say that these stories show us that spam is:

- Context-dependent and open to interpretation

- Delivered to non-consenting users

- Large-scale, random, and repetitive

- Impersonal

- Intrusive

Perhaps this is a controversial opinion, but I don’t see how spam is necessarily connected to commercial interests. These examples aren’t concerned about people making money or promoting services. They are upset because the businesses who spammed them promoted their services in a haphazard, intrusive way.

If you’re a brand, you must remember that users, websites, or platforms don’t owe you attention.

Spam, black hat SEO, or other “growth hacking” tactics arise from the same mistake: assuming that because you publish online or pay for ads, others owe you attention and sales.

SEOs are operatives within the system that they work in. If structural changes happen to that system, like Google pushing another core update to its algorithm, then SEOs will adapt to those changes. Our job is to help you get found online, remember?

And here’s the harsh reality: a search engine like Google doesn’t care about your website continuing to drive the same amount of traffic. Their function is to deliver “magic” to the user typing things into the search box.

And that magic comes from guessing what the user may want to see on the SERP, watching how they interact with results, and then adapting those results once that user (or another) searches for something again.

This means that Google is mostly website-agnostic. As Enge explained:

- “Google cares primarily about what questions/needs you address for their users. That often involves addressing many very specific questions, probably far more than meets the eye unless you have thoroughly researched all the various questions that relate to your market space. Develop the content to address these needs or give that Google traffic to someone else.”

You cannot force a platform like Google Search to guarantee traffic to your site. Because if you are not providing the kinds of answers users are looking for, you shouldn’t show up for their search results. To imagine otherwise is to fundamentally misunderstand the incentives at play.

- “People that don’t understand these things are not bad people, they’re just ignorant of the realities of the way the market works,” Enge said.

So, who are spammers? The people and organizations who force themselves to be visible anyway, because they think they’re entitled to attention. And when they manage to force themselves into the SERP or your internet experience in some way, that’s when we are talking about spam and “clogging the internet”.

As Brendan Hufford, founder of Growth Sprints, told me:

- “We’re having a ‘tactics’ debate, but we’re really having a ‘quality’ debate. We’re not debating SEO as a tactic. We’re talking about whether SEO is good. SEO ruined the internet because people did it badly, with content that’s not good. So if I make a bunch of mediocre stuff, that is not helpful. It doesn’t serve people.”

That mediocre content being shoved in your face is why you might feel like Google search is not that good anymore. So, why are you seeing it?

Digital ads: Why the internet only has one business model

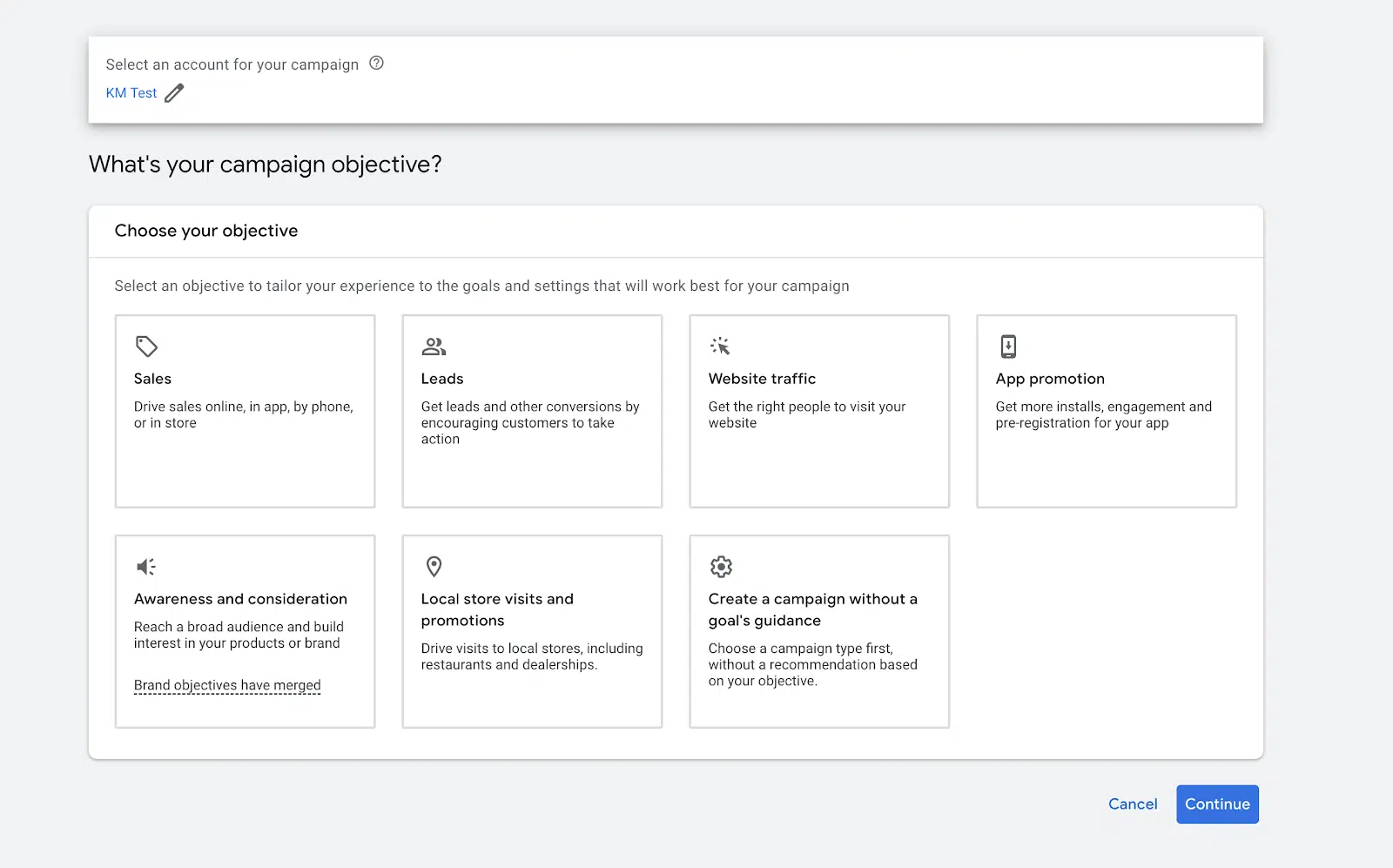

Let’s go back to that Groupon ad. When discussing the internet or search, we need to remember how money fits into the equation.

Most of Google’s revenue comes from digital ads. So, as much as the search engine may wish to serve users the most helpful results, we can’t ignore the “sponsored” aspect of the SERP.

We need to distinguish between two types of marketing:

- Organic marketing: Made up of information, pages, and posts that operate on the same playing field as any other content, surfaced by an algorithm or shared by people directly.

- Paid marketing: Content and links that are paid to be shown, otherwise known as “advertising.”

So far, we’ve mostly touched on the core work of SEO – optimizing for organic visibility and playing by the rules of search engine algorithms. We make useful content, listen to guidelines and anticipate what users want to see.

But when most search results, websites, and social media platforms offer options for “sponsored” content, that playing field is no longer level.

To truly address the Verge’s criticism, we have to speak about algorithms that underlie both organic and paid marketing. As explained by my friend Ronnie Higgins, director of content at OpenPhone:

- “People who game algorithms aren’t just an SEO problem. Social influencers and creators have been doing the same thing for 20 years and counting.”

I’d take it further: gaming algorithms to make more money online is a problem fundamental to the fabric of the internet itself.

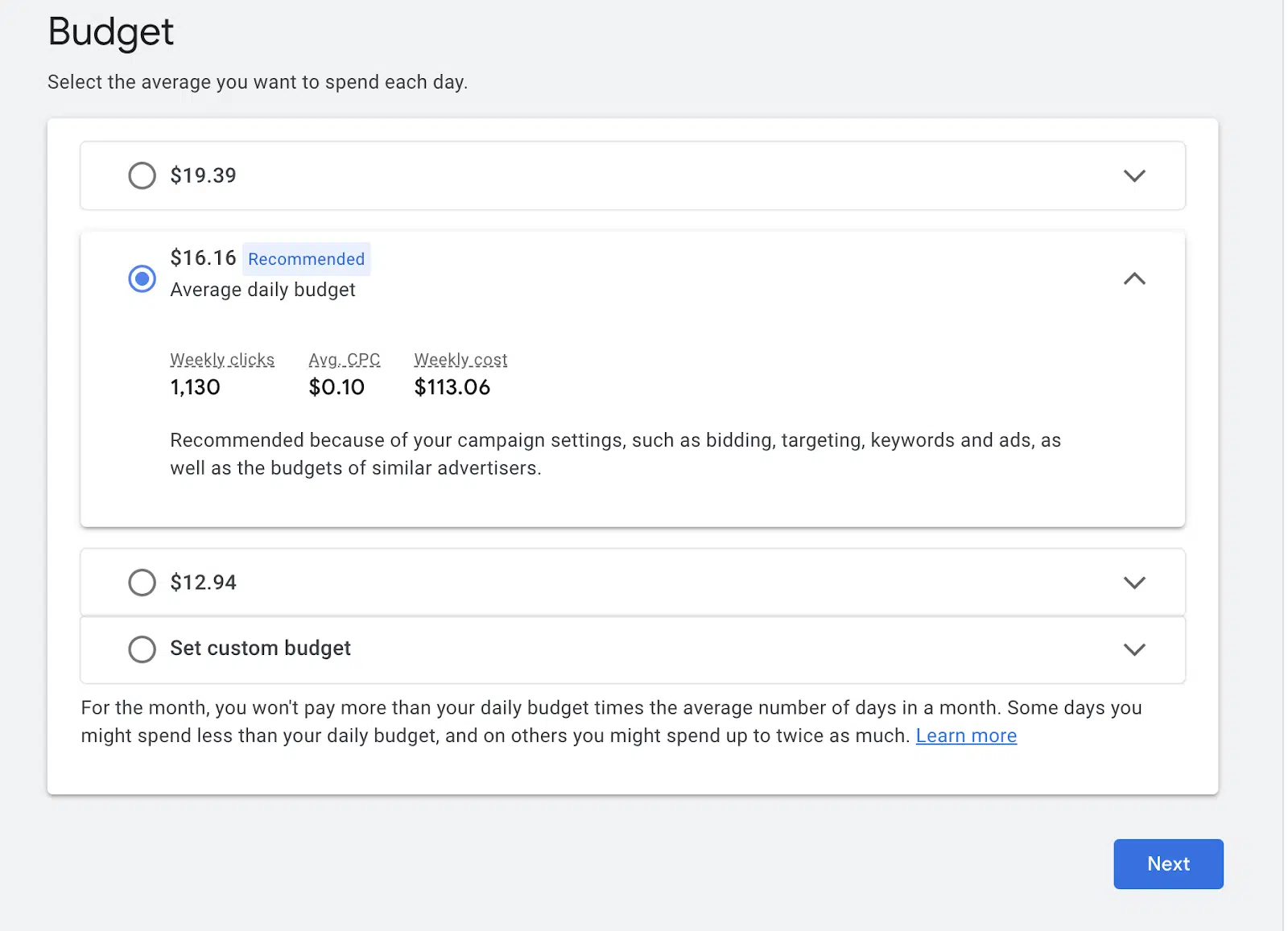

Because, at the end of the day, our work as SEOs conforms to the overarching business model that supports the internet and trickles down to search engines and individual websites. And that business model is pay-per-click (PPC) and programmatic advertising.

Various companies, including Google, offer businesses predictable exposure on their online platforms based on a buyer’s willingness to pay.

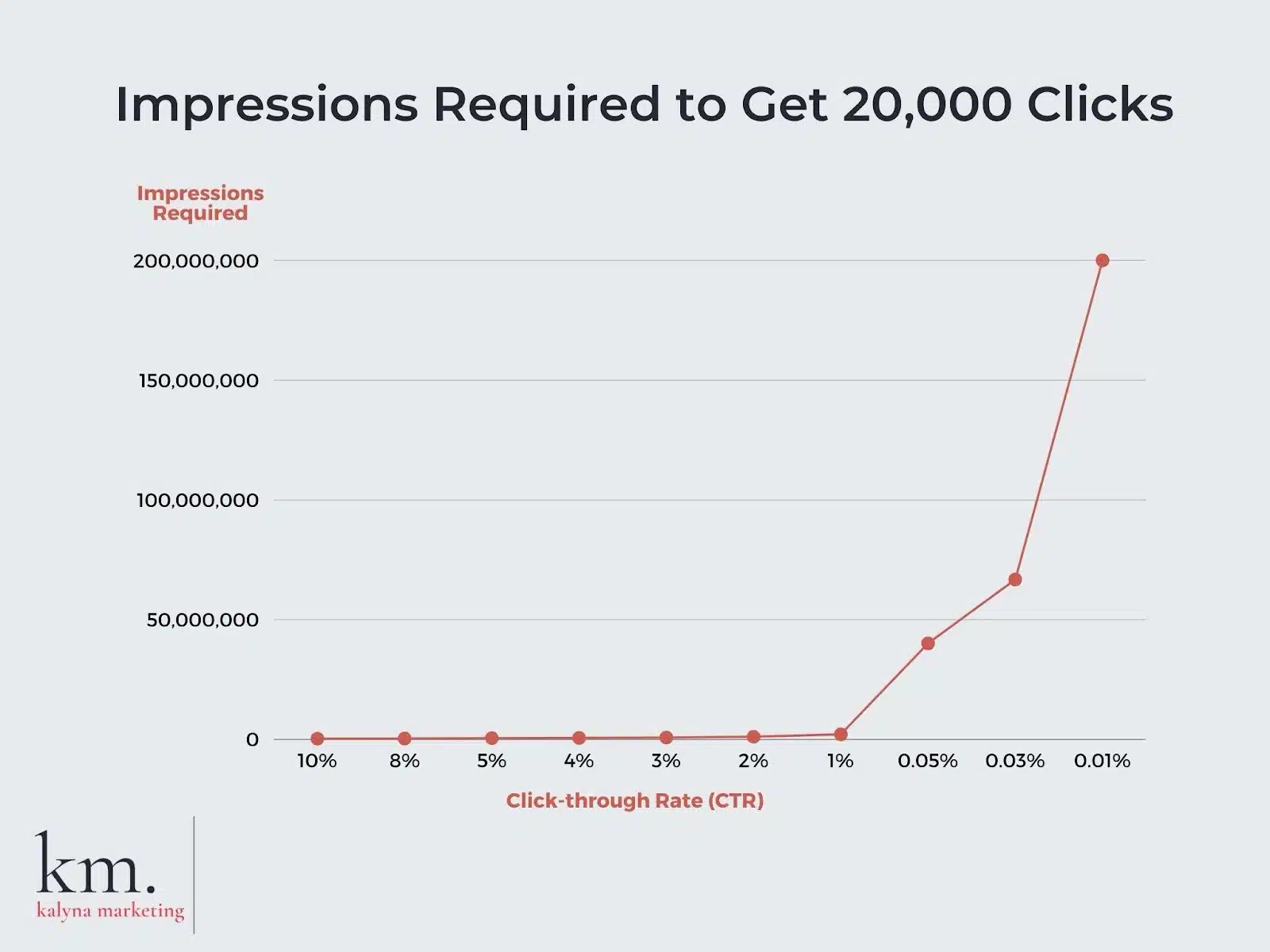

The numbers that make up this business model are simple:

- Impressions: The number of times your ads have been shown to users.

- Cost-per-click (CPC): The average amount you pay to get one user to click through to your website.

- Click-through rate (CTR): The amount of clicks on your ad divided by the amount of impressions.

- Conversion rate: The percentage of ad clicks that results in a desired action, typically a sale.

- Cost per conversion (also CPC): The cost of an ad campaign divided by the amount of conversions.

This system is so elegant and simple. If you’d like to get attention online, you can choose to pay for exposure on a variety of marketing channels – search, YouTube, social media like Facebook, a large ad exchange, a newsletter, a podcast, or more.

“The ad buyer is an investor of a sort, choosing how to allocate limited resources across many different types of promotions that offer different kinds of returns.”

– Tim Hwang, “Subprime Attention Crisis”

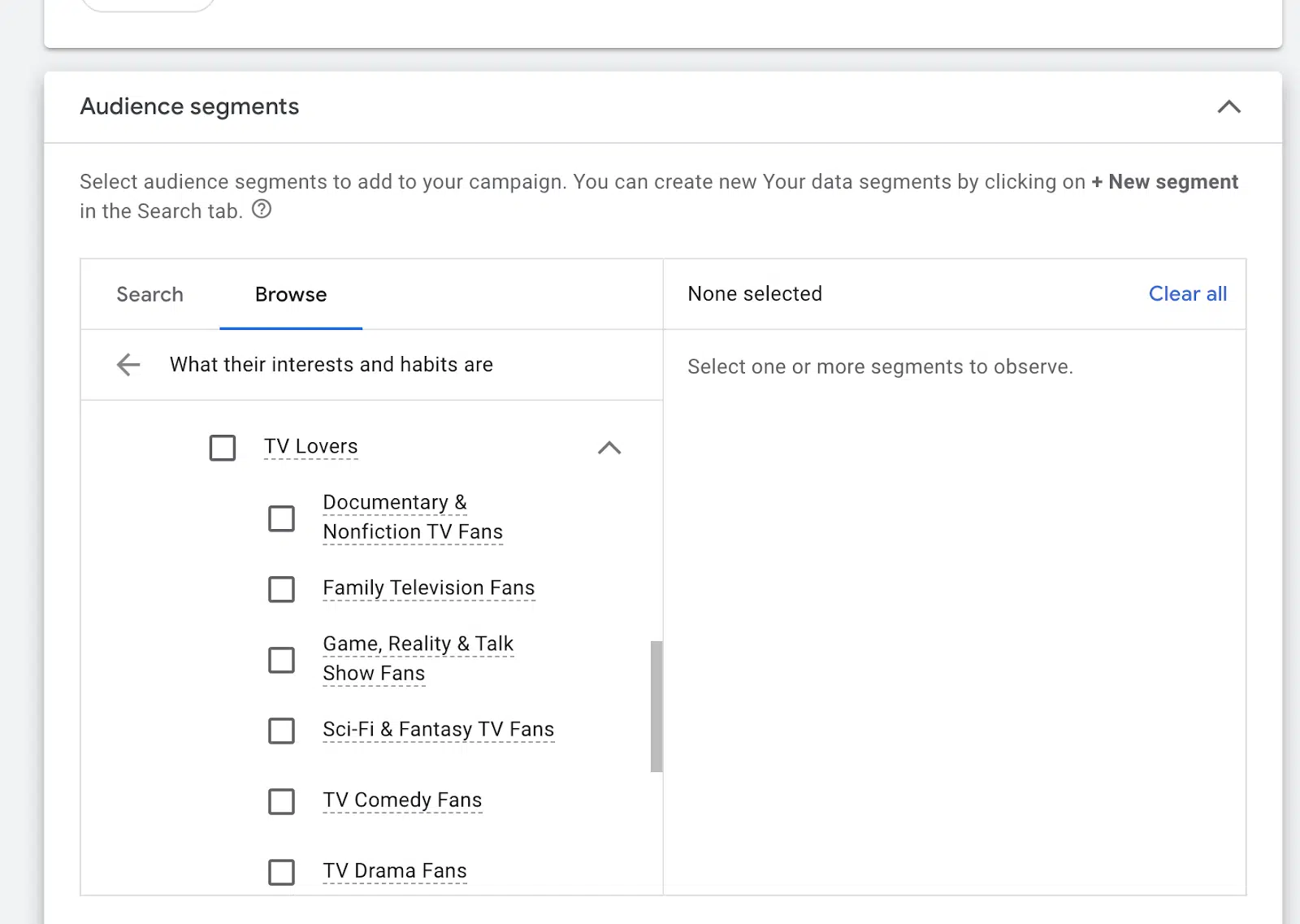

And when using a standardized ad platform like with Google Ads, you get to make your bids via a predictable, clear interface.

- “In this context, online platforms like Facebook and Google offer new, shiny assets in the broader marketplace for grabbing attention,” Hwang writes.

The way these platforms are set up, the only obstacle standing between your business and the attention you crave is your own wallet. You can purchase the success of any marketing goal.

PPC treats the internet as an infinite supply of little slices of every user’s attention, up for sale to the highest bidder. You simply have to click some buttons, specify the text and media that will show up on your ad, and off you go.

Websites with audiences can choose to rent access to those audiences out to other parties by offering up ads.

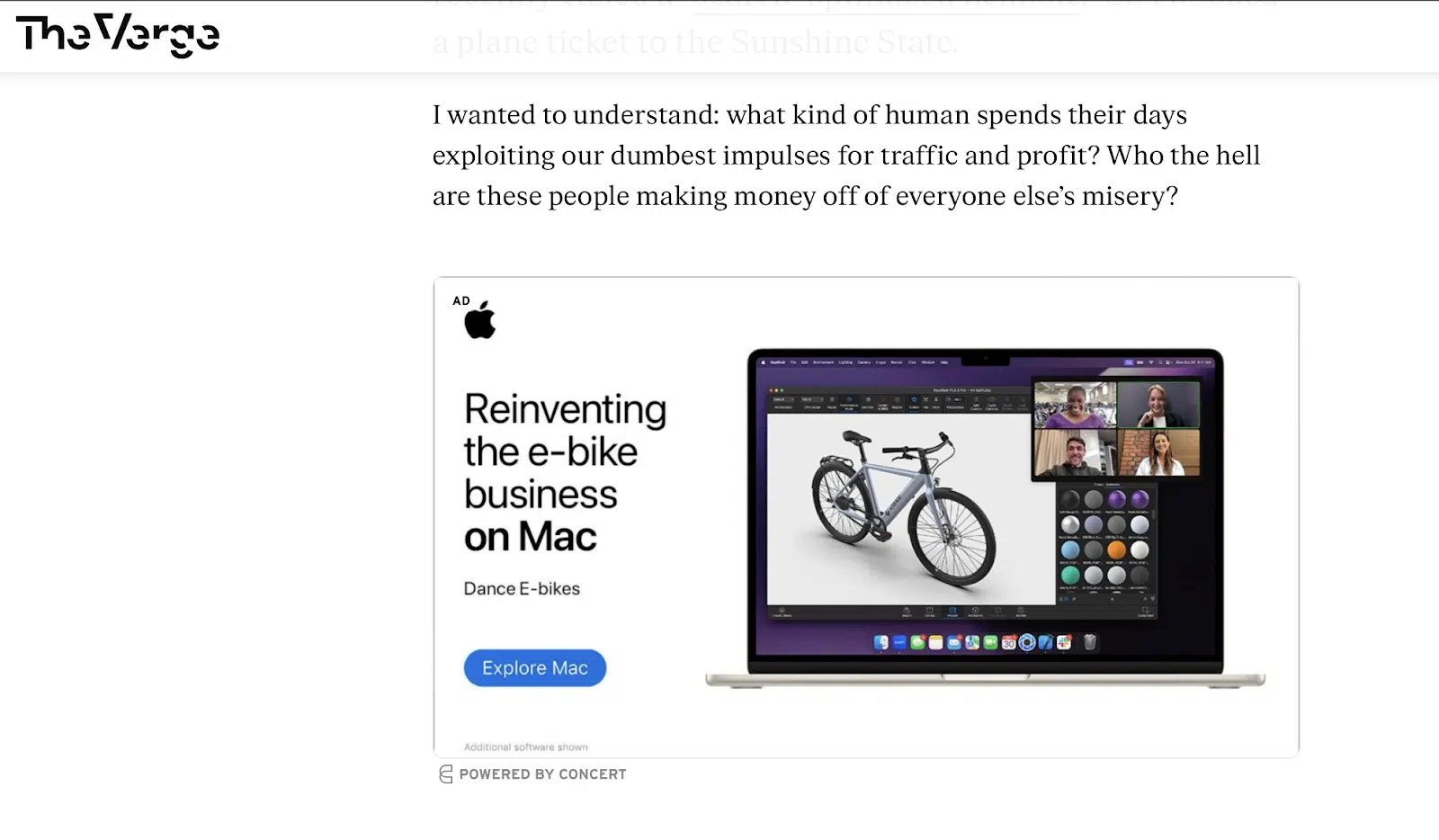

For instance, The Verge monetizes their own articles this way, including the very piece where they complained about everything online becoming about “selling stuff.”

- “As a company The Verge is probably getting paid when you go to their website, it’s chock full of ads. They’re making money off views. It’s just a different monetization model and a different traffic source,” Hufford told me.

It’s all on the table: every scroll, every click, every last millisecond of attention. And we are all sick of it.

Privacy, third-party cookies, decreasing efficacy of digital ads

Ads have become an infinite money button for too many companies that market themselves online. As Rand Fishkin wrote on his SparkToro blog:

“Almost every link a marketer placed on the web, every ad they bought, every search ranking they achieved, and every social network post contained easily collectable data showing where their efforts were working. Marketers (and even more so, company leadership) got addicted to this trackability.”

I agree. We’ve all gotten hooked on the drug that is digital advertising.

It’s hard to step away from an interface that allows you to pump more money in while promising a consistent supply of money out.

But the promises of that infinite money button turned out to be resting on a faulty foundation.

You see, the predictable tracking of return on investment (ROI) and the ability to show ads to the precise people you wanted to reach were based on collecting too much user data.

As Emily Gertenbach, B2B content writer at (e.g.) creative content, explained to me:

- “Our internet usage is increasingly tracked, monitored, parsed, and sold. We’re all largely tracked much more than we need to be. Companies collect far more data than is actually necessary to carry out various marketing activities, because we’ve been conditioned to believe that providing—and accepting—hyper-personalized marketing is the right or modern thing to do.”

The Cambridge Analytica scandal showed us that allowing companies like Facebook to collect unlimited data wasn’t a good idea, to say the least. As a result, we’ve been witnessing a rapid increase in data privacy regulations from governments and restrictions from certain tech companies and collectives, which means that digital advertising suddenly got a whole lot harder.

But because so much of the internet has already become conditioned to having easy access to tracking and identifying users for advertising… the mindset shift is difficult.

What happens when ads stop working?

But without overly intrusive tracking capabilities, digital ads aren’t working so well. As demonstrated in a recent academic paper by Nico Neumann et al.:

“While we find that deterministic data segments perform marginally better than probabilistic data segments, our results show that both types of these third-party audiences do not lead to better outcomes than random prospecting.”

Or, in plain English – advertising platforms aren’t good at predicting which users they should show ads to based on whether they are likely to match a certain audience persona (for example, a specific type of professional like an IT executive). Those predictions were so poor that you’d be better off simply showing ads to random users based on a roll of the dice or reading a Tarot deck.

And when ads become less good at figuring out who might want to see them, those ads tend to perform much worse for advertisers. If your product is aimed at 30-35-year-old suburban moms, but your ad gets shown to 14-year-old boys – not many of those views will turn to clicks, let alone sales.

But here’s where things get tricky: how do companies respond when their ads are suddenly resulting in fewer sales?

Since businesses don’t want to lose money, when sales drop they are likely to invest more into marketing or sales. And when the marketing channel used to work was digital advertising, those businesses are likely to increase their ad spending to compensate for lower conversions.

For instance, if you used to get 20,000 clicks at a 4% conversion rate, you needed your ads to have 500,000 impressions. But if now your ads are converting only at 1%, then to maintain the same amount of traffic to your site (20,000 clicks), you’ll need to show those ads 2,000,000 times.

This means that as ads convert at lower rates, companies try to chase the same results by making their ads more intrusive and showing those ads to more and more people.

As ads become less effective, the amount of web spam can increase. Businesses are chasing the promise of past performance that is getting harder and harder to reach, and they are frustrated because they can’t get another hit.

Get the daily newsletter search marketers rely on.

How organic marketing hasn’t been allowed to exist

Now that we’ve talked about paid advertising, let’s return to SEO.

The problem with organic marketing is that it’s a lot less clear-cut than paid ads used to be.

- “Creating the right content is a difficult task,” Enge said.

Organic marketing is hard to do and even harder to explain to people with control over marketing budgets. As Walker explained:

- “There’s not an experienced veteran I know who hasn’t had to spend a significant portion of their time back peddling or having to justify their existence, after losing rank, and not knowing why it dropped, or really, honestly, scientifically, knowing how it got to its position in the first place. We have hunches and best practices, but there’s also a lot of luck and finger-crossing and hoping for the best.”

Incentives and assumptions created by digital ads

Unfortunately, the alluring promise of perfect trackability and low barrier-to-entry with paid ads has made it difficult for many businesses to understand how difficult marketing without those ads truly is.

Most SEOs working with content are doing a ton of work. With content, we have to remember the audience who we are making it for.

- “No SEO represents the ‘average consumer.’ Do the research, track the journeys, hold the focus groups,” Forrester said.

In addition to customer research, as SEOs we also need to keep track of changes made by platforms like Google to their algorithms, since:

- “At the end of the day Google is the driving force behind the types of content that perform well, the logic behind it, and the types of results that show up for specific terms,” said Tory Gray, senior SEO consultant at Gray Dot Company.

But because digital advertising has provided companies with beautiful dashboards, clear numbers, and easy ROI calculations (such as cost per lead or return-on-ad-spend, ROAS) – there’s been pressure on organic marketers to keep up and have their own set of clear numbers and graphs.

Except, you can’t force organic marketing into an empirical box. You can try. You can add quantitative factors. You can make predictions.

But you can never fully guarantee or attribute performance of any organic marketing campaigns. Because you can’t quantify or reliably predict the complexity of human emotions and behavior.

But finance-oriented executives don’t accept that level of uncertainty. They want to ensure that their marketing investments deliver results. Which results in a fundamental incompatibility between executive expectations and the creative uncertainty inherent in most marketing work. And when marketers can’t prove why their work is valuable, their budgets get cut.

As a result, organic marketers try to do the same things as paid advertisers – chasing large reach, assuming low conversion rates, thinking about campaigns in isolated silos, and hoping for perfect attribution.

Essentially, we are all stuck in a self-fulfilling cycle of marketing failure.

Reach at all costs

This is time to admit: the Verge was right that some SEOs are making the web worse.

There are people who cover blogs in what we call “thin content,” endless variations of existing webpages and repetitive arguments rephrased from other websites. Bad SEOs exist.

- “SEO gurus that ‘consult’ and don’t deliver results are a dime a dozen (and there are dozens),” said Sarah Stockdale, founder of Growclass.

Some companies are hiring writers or paying for AI to churn out 50 blog posts a month, setting targets to write 5,000 words in every single post (as opposed to churning out an occasional 7-8,000 word manifesto as any good marketer obviously should do, right?).

They don’t care about whether they are introducing anything new to the conversation. They simply want to steal the traffic that they believe they are entitled to.

These companies are often referred to as “content mills.” Many of us have been caught in their trap at some point: we may have accidentally hired them or even worked for them ourselves. I started out as a freelance content writer on Upwork and churned out blog posts for $0.01 a word or less.

These marketing practices exist because of the reach-at-all-costs mentality that we see with ads. When you assume that all conversion rates are low and that the only way to get people to buy from you is to annoy or trick them into clicking on your links – your only leverage is content volume.

Content mills tend to track traffic and nothing else: they show dashboards with the amount of views, visitors, and keywords that sites rank for as proof of results. And they never stop to look at how long people might stay on webpages or whether they are the right people to be sending to those pages to begin with.

The real problem with this mindset isn’t just that it’s annoying for users. It’s that this approach doesn’t actually work.

I once spoke with a friend who told me that their startup was afraid of doing any more marketing. Why? Because their sales team became so swamped with random traffic and sales call sign-ups, they were burnt out trying to get through all of those “leads”, desperately searching for anybody who could actually become a customer.

When you put out spam content or ads onto the web, you get spam attention back. Clog the web with garbage, clog your operations with irrelevant visitors who won’t buy from you. Play stupid games, win stupid prizes.

Optimizing for reach is a race to the bottom. If you think marketing is too saturated, you’ve already lost. Because if you market to everyone, you are truly marketing to nobody.

The alternative is learning to understand your audience and the people you’d like to attract. But here’s the catch: it requires making truly good content that your target audience actually wants to see. And making good content is really hard.

As Enge explains, you need to:

- “Research user needs in detail, learn what questions they have, and determine what content needs to be created and what information architecture needs to be created to make it easy for users to navigate. These are tasks that require a large amount of effort.”

Remember, spam is context-dependent.

No topic, product, or company is inherently “spam.” But once you’re churning out enough content to fill a bookshelf every couple of days, then it’s spam! That’s all that those promotional efforts could ever be.

Let’s return to The Verge now, because the issues that we’ve explored with marketing, ads, and SEO aren’t isolated to just us. They are also extremely familiar to any journalist working in the field today.

As Goodwin explains:

- “Most SEOs and journalists aren’t that different. My college degree is in journalism. SEO, journalist, whatever the job titles, the end goal is really about informing, educating, entertaining and – yes – sometimes selling.”

And how could we be different?

After all, both media companies and marketers are trying to create web pages that get attention. We both operate on social media, video platforms, blogs, and even search engines. Our desired audiences are often the same people, browsing the same internet from the same mobile phone or computer.

As we compete for attention and reach in this world of broken economic incentives, we end up making the same mistakes. As Hufford pointed out:

- “The Verge are playing the SEO game just as much as anybody else. There’s no way that they have 1000 people linking to their best cell phones page organically. Those links are paid for (or traded for).”

Journalists are also caught in the cycle of marketing failure.

Because so many media companies are reliant on PPC advertising to support their businesses, they need to flood their pages with ads and produce as much content as possible to show those ads.

But a website is only paid for ads that actually get viewed and clicked on. So media publications like The Verge are incentivized to drive traffic however they can.

For instance, many of us suspect that’s why The Verge published that SEO piece in the first place. As Walker summed up “it wouldn’t surprise me if it was intended to tap into a niche community to manufacture outrage and drive up page views.”

This is, in the field, known by the obscure term “clickbait.”

Clickbait and chasing rage engagement

Look, that article was… strange. It felt engineered to make our entire field angry.

The Verge got many details wrong. For instance, Ray told me that “the now infamous ‘alligator party’ wasn’t even a true SEO event, but rather a casual meetup for affiliate marketers.”

It seemed like the whole point of that piece was simply to create “spicy drama.” For instance:

- “Amanda (the author) did all this research, attending the party, talking to folks, and somehow never realized her own preconceived bias prevented her from learning anything,” Higgins explained.

And yes, it worked. As I’ve shown above – all of us in marketing and SEO are already worried about our field. We feel like marketing, as we know it, might be falling apart. And this article dug into our insecurities.

As Walker described:

- “In a lot of ways, I feel like it was kicking people when they were feeling down, because it was the darkest reflection of what we all fear deep down.”

Walking away from the casino: Why people are giving up

Again, The Verge isn’t an isolated actor in our online wasteland. I agree with Hufford that “the game that The Verge is participating in, we’re all playing it.”

The digital marketing status quo is broken. It’s not working for users, websites, journalists, or marketers. And figuring out how to change that status quo is hard. So many people are looking at the state of things and deciding that everything is hopeless.

Giving up on targeting

Chasing reach at all costs is a form of giving up. If you are trying to chase those hundreds of thousands or millions of impressions, that means you’ve given up on any concept of niche or properly targeting your content to a relevant audience.

Mass marketing becomes your only form of marketing. Because if your ads aren’t reaching the right people – might as well just throw money into the dark and hope that it comes back in the form of some views, from anybody, who cares who they are?

Typical SEO keyword research boils down to believing that “the way to run a content strategy is we do our keyword export, we sort for highest volume and lowest difficulty, and there’s your content strategy. I think that needs to go straight into the toilet.” As Hufford told me.

When the old way of tracking users is breaking down, we aren’t sure what to do instead. As explained Gertenbach described, we’re feeling:

- “Disillusionment with our hyper-tracked, hyper-monetized, and hyper-advertised world of media consumption. And I don’t think the author knew quite how to separate out the different parts of modern marketing culture that create that sensation. Which is understandable—it’s complex!”

Giving up on marketing

Others might give up on the practice of marketing entirely. And perhaps part of that is our fault. As Montserrat Cano, international SEO consultant, told me:

- As SEOs “we tend to do a bad job at marketing ourselves and what we do.”

People are told that to promote themselves. They need to either play the reach-at-all-costs game or give up. So the false conclusion that the public is encouraged to reach boils down to “all marketing bad.”

For instance, Elizabeth Tai replied to me the other week wondering about the future of the web, and she wrote:

- “I wonder how marketers will navigate this space or are they even allowed in.”

So many people think we are ruining the internet. It’s not just the Verge. As Walker described:

- “Our community is having an existential crisis where many people have been feeling, to some extent, some truth to what the article was saying. Many people I know have been questioning whether or not they’re being helpful or just spinning their wheels to appease the search engines.”

Giving up on the internet

Some go as far as to start believing that the entire internet is ruined or may have been a mistake.

But how can that be? The internet isn’t static. As Becky Hendriksen, CEO of Green Hearted, explained to me:

- “An internet that stops evolving is ruined. A non-ruined internet will continue to shift and adapt.”

So if we give up on the internet, we are dooming it to fail.

What if things could change?

What if we refuse to give in to nihilism? What if we actually try to salvage what has been great about niching down, marketing, and the internet itself?

After all, things have changed before.

SEO used to be very different even a few years ago. As Eugene Zatiychuk, one of my clients and SEO lead at Belkins, told me:

- “You could get the top position in Google with some spam-ish techniques. But five years ago, Google improved because of things we, SEOs, have done. And they actually updated the algorithm to combat abuse. And now, it’s almost impossible to do spam. So you can do it. It just doesn’t work.”

Google has changed how it ranks pages, and the spammy tactics of previous years are no longer prevalent or effective. How? As Schwartz, president at RustyBrick, Inc. and contributing editor to Search Engine Land, said:

- “We just cracked down. What was ‘accepted’ 20 years ago is simply not today and for good reason.“

Where search is moving

Google has been pushing many updates to prioritize niche, targeted, and user-centric content.

This means that for pages to rank, they should show why a particular author is qualified to speak on a topic. As Lam explained:

- “For example, if a website produces a blog comparing pros and cons of visiting different national parks, but the writer has never visited those parks, there’s no clarity on who the writer is – then that blog will be considered low quality. And in theory, it should not be easy to find on Google. This is great for searches, because we don’t want recommendations from sources that don’t have first-hand expertise and experience to draw on.”

Fixing the internet: Refuse the sucker’s choice

Look, SEOs aren’t a different breed of human. We are also internet users who want to have a good time online and help others navigate the web.

- As Stockdale said, “most marketers focused on SEO just want to do good work and help their companies and clients be seen in an increasingly noisy content environment.”

The internet doesn’t have to be toxic sludge (or even a cesspool, as former Google CEO Eric Schmidt once called it way back in 2008). It can also make us better. For example, Lam told me:

- “For me, as a mom, a wife, a leader, and simply as a human, I appreciate the internet, because it gives me instant access to the information and inspiration I need to be the best (and honestly, less anxious) version of myself.”

But to improve the good, we need to make changes. I agree with Gertenbach, who said:

- “To change the fundamental dissatisfaction expressed in (The Verge) article, we’d have to take a broader look at how we (as a society) consume, demand, create, and monetize content.”

We should do things the right way. Which means that as SEOs, we must remember what our jobs are meant to do:

- “As findability specialists, we help to surface and maximize the visibility of what’s needed at each stage of the users’ search journey, whatever the platform or the format.” explained Solís.

We aren’t on opposite teams from regular users or journalists. And we can educate our field to think differently. For instance, here’s how Stockdale teaches SEO at Growclass:

- “Selling something should mean connecting someone with a problem to a useful solution, not tricking them. We teach modern marketing, focused on the needs of the customer, and delighting people.”

What truly ruined the internet: Erasing humanity out of our online experiences

We should let everyone be human.

Marketers should be trusted to market how they think is right. Reviewers and influencers should be trusted to describe their real experiences with products. And users and buyers should be trusted to figure out what they should buy for themselves.

The dependence on large ad networks has become like the ideal espoused by crypto – a fully zero trust system with no human intervention or appreciation for humanity in the mix. And in surrendering our humanity, we’ve helped create a spam-ridden wasteland.

This isn’t a story about SEOs, the Verge, or any particular group. This story is about humans who go online and want to connect with others. And that story can easily have an optimistic future.

After all, as Gertenbach told me:

- “There’s plenty of room to create content and digital experiences that answer questions people are searching for online.”

I won’t pretend to know what that future would look like. But I do know that we won’t get there by calling each other “goblins.”

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the guest author and not necessarily Search Engine Land. Staff authors are listed here.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land

https://searchengineland.com/un-ruin-internet-ultimate-guide-seo-434764