30-second summary:

- Content managers who want to assess their on-page performance can feel lost at sea due to numerous SEO signals and their perceptions

- This problem gets bigger and highly complex for industries with niche semantics

- The scenarios they present to the content planning process are highly specific, with unique lexicons and semantic relationships

- Sr. SEO Strategist at Brainlabs, Zach Wales, uses findings from a rigorous competitive analysis to shed light on how to evaluate your on-page game

Industries with niche terminology, like scientific or medical ecommerce brands, present a layer of complexity to SEO. The scenarios they present to the content planning process are highly specific, with unique lexicons and semantic relationships.

SEO has many layers to begin with, from technical to content. They all aim to optimize for numerous search engine ranking signals, some of which are moving targets.

So how does one approach on-page SEO in this challenging space? We recently had the privilege of conducting a lengthy competitive analysis for a client in one of these industries.

What we walked away with was a repeatable process for on-page analysis in a complicated semantic space.

The challenge: Turning findings into action

At the outset of any analysis, it’s important to define the challenge. In the most general sense, ours was to turn findings into meaningful on-page actions — with priorities.

And we would do this by comparing the keyword ranking performance of our client’s domain to that of its five chosen competitors.

Specifically, we needed to identify areas of the client’s website content that were losing to competitors in keyword rankings. And to prioritize things, we needed to show where those losses were having the greatest impact on our client’s potential for search traffic.

Adding to the complexity were two additional sub-challenges:

- Volume of keyword data. When people think of “niche markets,” the implication is usually a small number of keywords with low monthly search volumes (MSV). Scientific industries are not so. They are “niche” in the sense that their semantics are not accessible to all—including keyword research tools—but their depth & breadth of keyword potential is vast.

- Our client already dominated the market. At first glance, using keyword gap analysis tools, there were no product categories where our client wasn’t dominating the market. Yet they were incurring traffic losses from these five competitors from a seemingly random, spread-out number of cases. Taken together incrementally, these losses had significant impacts on their web traffic.

If the needle-in-a-haystack analogy comes to mind, you see where this is going.

To put the details to our challenge, we had to:

- Identify where those incremental effects of keyword rank loss were being felt the most — knowing this would guide our prioritization;

- Map those keyword trends to their respective stage of the marketing funnel (from informational top-of-funnel to the transactional bottom-of-funnel)

- Rule out off-page factors like backlink equity, Core Web Vitals & page speed metrics, in order to…

- Isolate cases where competitor pages ranked higher than our client’s on the merits of their on-page techniques, and finally

- Identify what those successful on-page techniques were, in hopes that our client could adapt its content to a winning on-page formula.

How to spot trends in a sea of data

When the data sets you’re working with are large and no apparent trends stand out, it’s not because they don’t exist. It only means you have to adjust the way you look at the data.

As a disclaimer, we’re not purporting that our approach is the only approach. It was one that made sense in response to another challenge at hand, which, again, is one that’s common to this industry: The intent measures of SEO tools like Semrush and Ahrefs — “Informational,” “Navigational,” “Commercial” and “Transactional,” or some combination thereof — are not very reliable.

Our approach to spotting these trends in a sea of data went like this:

Step 1. Break it down to short-tail vs. long tail

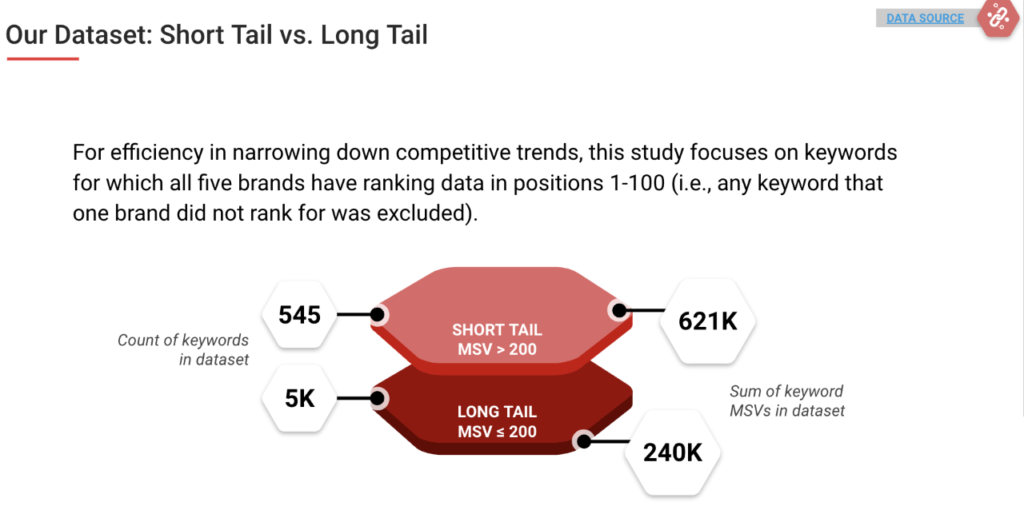

Numbers don’t lie. Absent reliable intent data, we cut the dataset in half based on MSV ranges: Keywords with MSVs above 200 and those equal to/below 200. We even graphed these out, and indeed, it returned a classic short/long-tail curve.

This gave us a proxy for funnel mapping: Short-tail keywords, defined as high-MSV & broad focus, could be mostly associated with the upper funnel. This made long-tail keywords, being less searched but more specifically focused, a proxy for the lower funnel.

Doing this also helped us manage the million-plus keyword dataset our tools generated for the client and its five competitor websites. Even if you perform the export hack of downloading data in batches, neither Google Drive nor your device’s RAM want anything to do with that much data.

Step 2. Establish a list of keyword-operative root words

The “keyword-operative root word” is the term we gave to root words that are common to many or all of the keywords under a certain topic or content type. For example, “dna” is a common root word to most of the keywords about DNA lab products, which our client and its competitors sell. And “protocols” is a root word for many keywords that exist in upper-funnel, informational content.

We established this list by placing our short- and long-tail data (exported from Semrush’s Keyword Gap analysis tool) into two spreadsheets, where we were able to view the shared keyword rankings of our client and the five competitors. We equipped these spreadsheets with data filters and formulas that scored each keyword with a competitive value, relative to the six web domains analyzed.

Separately, we took a list of our client’s product categories and brainstormed all possibilities for keyword-operative root words. Finally, we filtered the data for each root word and noted trends, such as the number of keywords that a website ranked for on Google page 1, and the sum of their MSVs.

Finally, we applied a calculation that incorporated average position, MSV, and industry click-through rates to quantify the significance of a trend. So if a competitor appeared to have a keyword ranking edge over our client in a certain subset of keywords, we could place a numerical value on that edge.

Step 3. Identify content templates

If one of your objectives is to map keyword trends to the marketing funnel, then it’s critical to understand the role of page templates. Why?

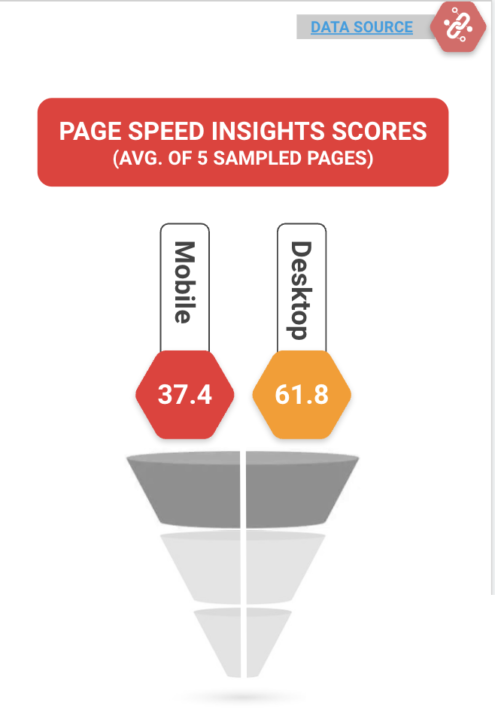

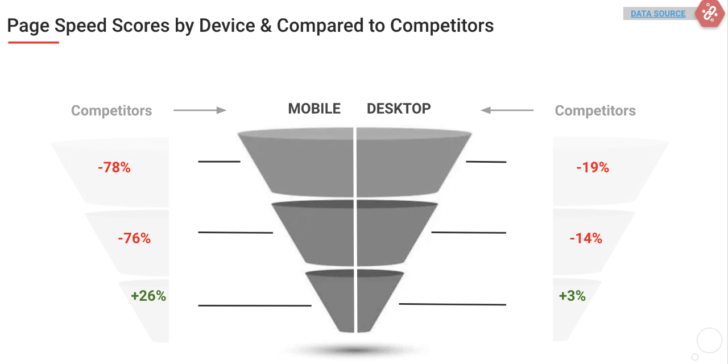

Page speed performance is a known ranking signal that should be considered. And ecommerce websites often have content templates that reflect each stage of the funnel.

In this case, all six competitors conveniently had distinct templates for top-, middle- and bottom-funnel content:

- Top-funnel templates: Text-heavy, informational content in what was commonly called “Learning Resources” or something similar;

- Middle-funnel templates: Also text-heavy, informational content about a product category, with links to products and visual content like diagrams and videos — the Product Landing Page (PLP), essentially;

- Bottom-funnel templates: Transactional, Product Detail Pages (PDP) with concise, conversion-oriented text and purchasing calls-to-action.

Step 4. Map keyword trends to the funnel

After cross-examining the root terms (Step 2), keyword ranking trends began to emerge. Now we just had to map them to their respective funnel stage.

Having identified content templates, and having the data divided by short- & long-tail made this a quicker process. Our primary focus was on trends where competitor webpages were outranking our client’s site.

Identifying content templates brought the added value of seeing where competitors, for example, outranked our client on a certain keyword because their winning webpage was built in a content-rich, optimized PLP, while our client’s lower-ranking page was a PDP.

Step 5. Rule out the off-page ranking factors

Since our goal was to identify & analyze on-page techniques, we had to rule out off-page factors like link equity and page speed. We sought cases where one page outranked another on a shared keyword, in spite of having inferior link equity, page speed scores, etc.

For all of Google’s developments in processing semantics (e.g., BERT, the Helpful Content Update) there are still cases where a page with thin text content outranks another page that has lengthier, optimized text content — by virtue of link equity.

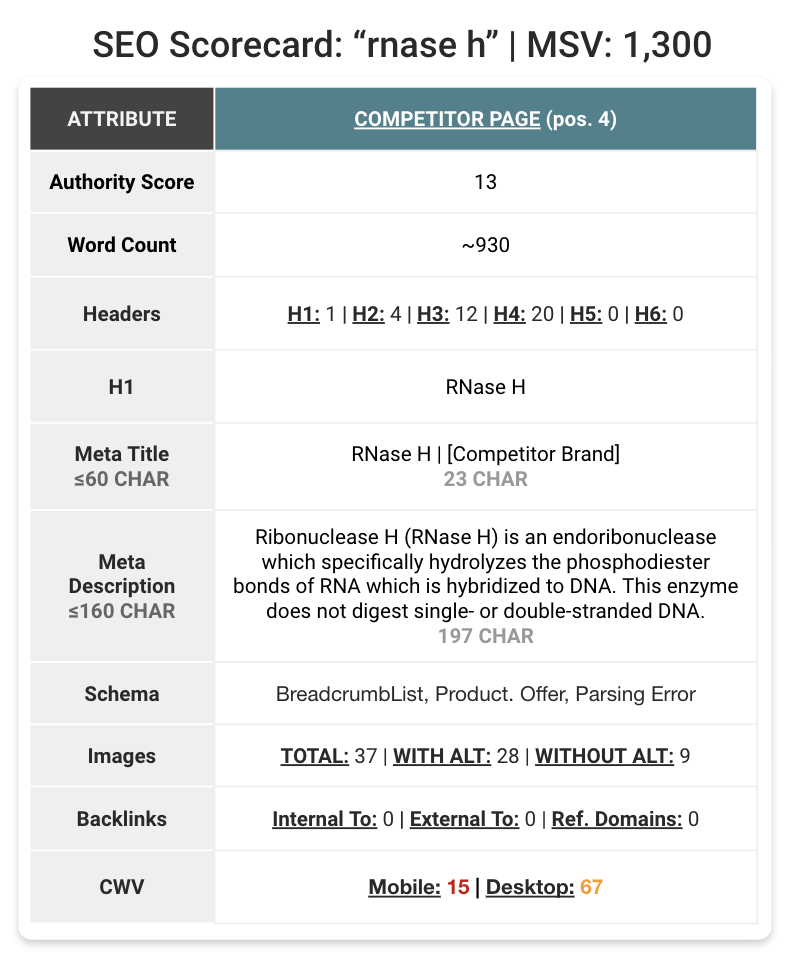

To rule these factors out, we assigned an “SEO scorecard” to each webpage under investigation. The scorecard tallied the number of rank-signal-worthy attributes the page had in its SEO favor. This included things like Semrush’s page authority score, the number of internal vs. external inlinks, the presence and types of Schema markup, and Core Web Vitals stats.

The scorecards also included on-page factors, like the number of headers & subheaders (H1, H2, H3…), use of keywords in alt-tags, meta titles & their character counts, and even page word count. This helped give a high-level sense of on-page performance before diving into the content itself.

Our findings

When comparing the SEO scorecards of our client’s pages to its competitors, we only chose cases where the losing scorecard (in off-page factors) was the keyword ranking winner. Here are a few of the standout findings.

Adding H3 tags to products names really works

This month, OrangeValley’s Koen Leemans published a Semrush article, titled, SEO Split Test Result: Adding H3 Tags to Products Names on Ecommerce Category Pages. We found this study especially well-timed, as it validated what we saw in this competitive analysis.

To those versed in on-page SEO, placing keywords in <h3> HTML format (or any level of <h…> for that matter) is a wise move. Google crawls this text before it gets to the paragraph copy. It’s a known ranking signal.

When it comes to SEO-informed content planning, ecommerce clients have a tendency — coming from the best of intentions — to forsake the product name in pursuit of the perfect on-page recipe for a specific non-brand keyword. The value of the product name becomes a blind spot because the brand assumes it will outrank others on its own product names.

It’s somewhere in this thought process that an editor may, for example, decide to list product names on a PLP as bolded <p> copy, rather than as a <h3> or <h4>. This, apparently, is a missed opportunity.

More to this point, we found that this on-page tactic performed even better when the <h>-tagged product name was linked (index, follow) to its corresponding PDP, AND accompanied with a sentence description beneath the product name.

This is in contrast to the product landing page (PLP) which has ample supporting page copy, and only lists its products as hyperlinked names with no descriptive text.

Word count probably matters, <h> count very likely matters

In the ecommerce space, it’s not uncommon to find PLPs that have not been visited by the content fairy. A storyless grid of images and product names.

Yet, in every case where two PLPs of this variety went toe-to-toe over the same keyword, the sheer number of <h> tags seemed to be the only on-page factor that ranked one PLP above its competitors’ PLPs, which themselves had higher link equity.

The takeaway here is that if you know you won’t have time to touch up your PLPs with landing copy, you should at least set all product names to <h> tags that are hyperlinked, and increase the number of them (e.g., set the page to load 6 rows of products instead of 4).

And word count? Although Google’s John Mueller confirmed that word count is not a ranking factor for the search algorithm, this topic is debated. We cannot venture anything conclusive about word count from our competitive analyses. What we can say is that it’s a component of our finding that…

Defining the entire topic with your content wins

Backlinko’s Brian Dean ventured and proved the radical notion that you can optimize a single webpage to rank for not the usual 2 or 3 target keywords, but hundreds of them. That is if your copy encompasses everything about the topic that unites those hundreds of keywords.

That practice may work in long-form content marketing but is a little less applicable in ecommerce settings. The alternative to this is to create a body of pages that are all interlinked deliberately and logically (from a UX standpoint) and that cover every aspect of the topic at hand.

This content should address the questions that people have at each stage of the awareness-to-purchase cycle (i.e., the funnel). It should define niche terminology and spell out acronyms. It should be accessible.

In one stand-out case from our analysis, a competitor page held position 1 for a lucrative keyword, while our client’s site and that of the other competitors couldn’t even muster a page 1 ranking. All six websites were addressing the keyword head-on, arguably, in all the right ways. And they had superior link equity.

What did the winner have that the rest did not? It happened that in this lone instance, its product was being marketed to a high-school teacher/administrator audience, rather than a PhD-level, corporate, governmental or university scientist. By this virtue alone, their marketing copy was far more layman-accessible, and, apparently, Google approved too.

The takeaway is not to dumb-down the necessary jargon of a technical industry. But it highlights the need to tell every part of the story within a topic vertical.

Conclusion: Findings-to-action

There is a common emphasis among SEO bloggers who specialize in biotech & scientific industries on taking a top-down, topical takeover approach to content planning.

I came across these posts after completing this competitive analysis for our client. This topic-takeover emphasis was validating because the “Findings-To-Action” section of our study prescribed something similar:

Map topics to the funnel. Prior to keyword research, map broad topics & subtopics to their respective places in the informational & consumer funnel. Within each topic vertical, identify:

- Questions-to-ask & problems-to-solve at each funnel stage

- Keyword opportunities that roll up to those respective stages

- How many pages should be planned to rank for those keywords

- The website templates that best accommodate this content

- The header & internal linking strategy between those pages

Unlike more common-language industries, the need to appeal to two audiences is especially pronounced in scientific industries. One is the AI-driven audience of search engine bots that scour this complex semantic terrain for symmetry of clues and meaning. The other is human, of course, but with a mind that has already mastered this symmetry and is highly capable of discerning it.

To make the most efficient use of time and user experience, content planning and delivery need to be highly organized. The age-old marketing funnel concept works especially well as an organizing model. The rest is the rigor of applying this full-topic-coverage, content approach.

Zach Wales is Sr. SEO Strategist at Brainlabs.

Subscribe to the Search Engine Watch newsletter for insights on SEO, the search landscape, search marketing, digital marketing, leadership, podcasts, and more.

Join the conversation with us on LinkedIn and Twitter.

https://www.searchenginewatch.com/2022/11/01/in-a-sea-of-signals-is-your-on-page-on-point/