July 31, 2020

John Boardley

Most histories of the poster begin in the nineteenth century in France during the Belle Époque, when artists and printmakers like Jules Chéret and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec raised the poster from cheap print to high art. The arrival of the modern poster coincides with the invention of lithography and chromolithography, which for the first time ever made color printing both practical and affordable. Remember that before the invention of chromolithography, if you wanted something colored, it was invariably colored by hand.

Lithographic poster by Jules Chéret, 1893.

Image: MoMa

But today, I’ll not recount that well-known history in nineteenth-century France. Instead we will head northeast to the fifteenth century, to Germany, to take a brief look at the poster before the poster, a kind of poster proto-history, if you like. There, in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe we’ll discover the poster’s distant Renaissance ancestors. But before we set off, a brief detour is in order, because it’s absolutely crucial that we understand that the poster — and the printed book — would not have been possible without one essential ingredient.

Paper Possible

Just as the invention of lithography made possible the modern poster, in the fifteenth century, it was the availability of inexpensive paper that made printed images and printmaking feasible. Prior to the introduction of paper (invented in China) into Europe in the eleventh century, everything was written on parchment (animal skins). The preparation of parchment is incredibly time-consuming, laborious, and expensive, and was never going to be sustainable. In the fifteenth century alone, tens of millions of pages were printed — impossible without paper. Consider that for the estimated forty copies of the Gutenberg Bible (c. 1455) printed on parchment, the skins of 3,200 animals were required!

Earliest datable European woodcut. Baby Jesus piggybacking on Saint Christopher. Hand-colored, c. 1423. Image from John Rylands Library

* Not that printing from woodcuts is a European invention. They appear centuries earlier in Asia

** See Thierry Depaulis, ‘L’apparition dela xylographie et l’arrivée des cartes à jouer en Europe’, Nouvelles de l’estampe, nos. 185-86, Dec. 2002-Feb. 2003, pp. 7-19

From Playing Cards to Baby Jesus

Woodblocks had long been used to print on textiles, but it was not until about 1400, in Europe,* that woodcuts appear printed on paper. Initially, they were used in printing small devotional images — scenes from the life of Jesus or portraits of the Virgin Mary, or of Christian Saints. At the same time, woodcuts were used to print playing cards, which had arrived in Europe in the 1360s.** The devotional images were popular items sold along pilgrim routes, sold as objects of private devotion, or as souvenirs. One of the great benefits of printing from woodblocks is that they can be printed without any special equipment, other than a hand or a spoon to rub the back of the paper. Intaglio printing techniques, however, require large roller presses, and expensive copper plates.

Relief to Intaglio

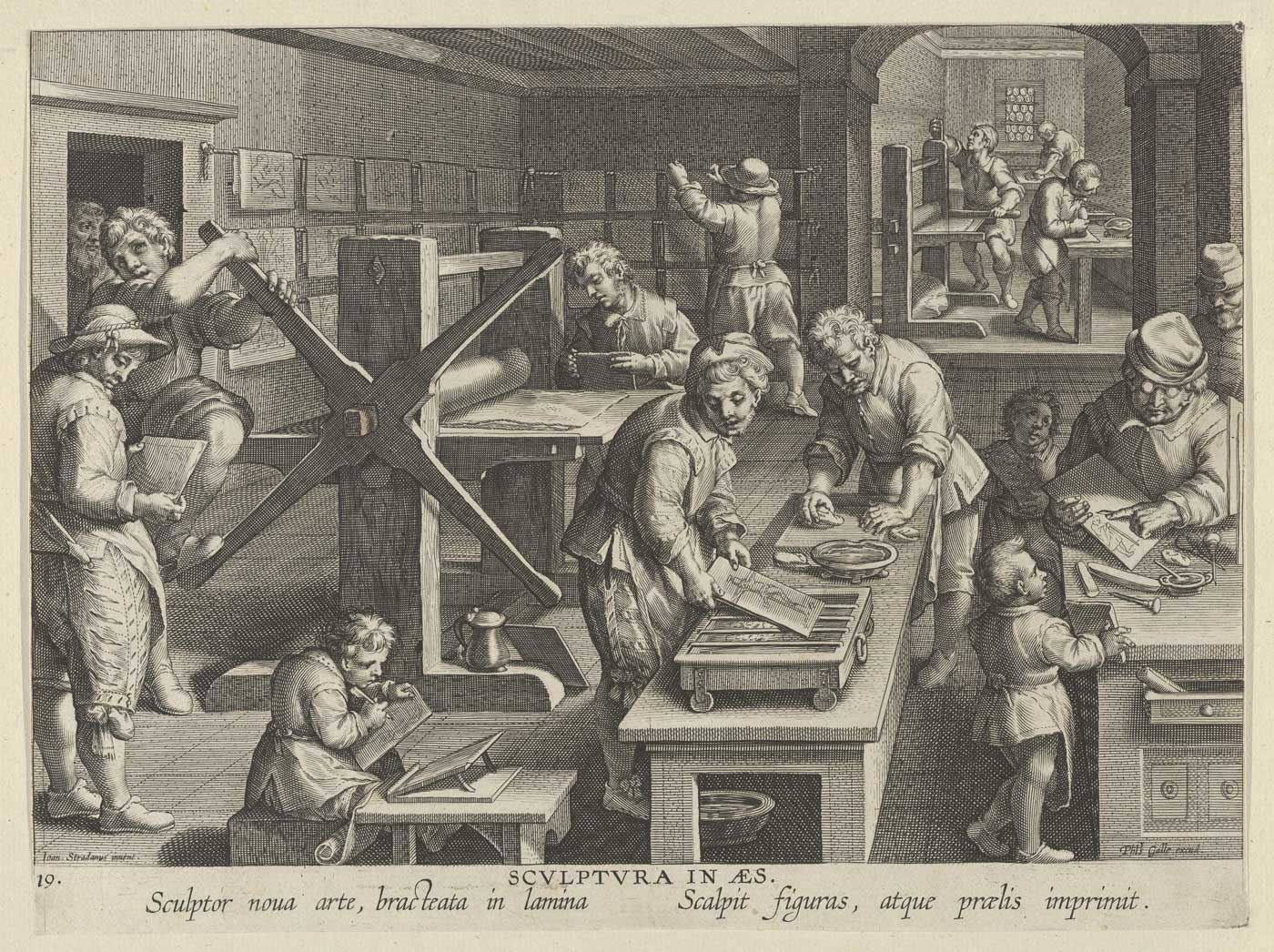

The sixteenth century witnessed a boom in printmaking and a gradual shift away from woodcut to intalgio techniques for printing images. The most popular were engraving, drypoint, and etching. Each method has its own distinctive characteristics. Engraving requires a special v-shape burin and produces clean lines. Drypoint is similar, but only requires a sharp needle to scratch the design onto the copper plate. A by-product of this scratching is a small burr — like dirt piled at the side of a freshly dug trench — and it is this microscopically small and irregular burr that picks up ink and prints a softer velvety line. Etching, that from the seventeenth century became the preferred intaglio technique, permits the most freedom in drawing the design. A copper plate is first coated in a thin layer of acid-resistant ground. A needle is then used to ‘draw’ the design onto the plate, in the process exposing the metal below the thin ground. Once finished, the plate is brushed or bathed in acid that eats into the exposed (drawn) parts of the plate, thus etching the drawn design permanently into the copper plate. All of these techniques could also be combined in a single print. Rembrandt was a master of combining intaglio techniques to remarkable effect (see the three plates at the end of this article).

The Elephant & the Rhino

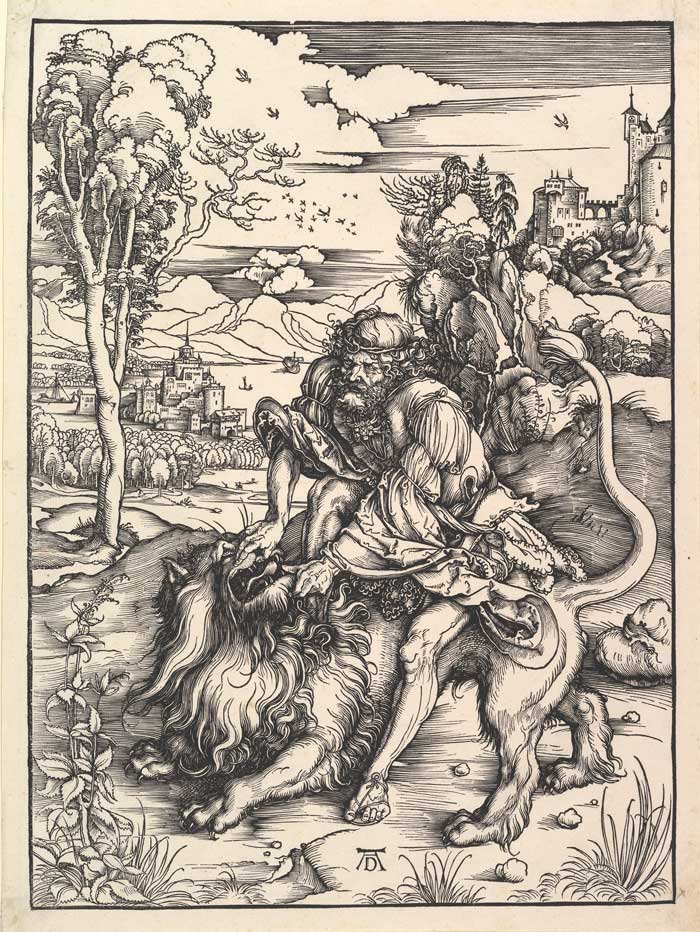

Prints could be sold individually or bound into slim volumes. As an inducement to collect, prints were often produced as part of a series; for example, The Seven Deadly Sins, The Four Seasons, The Virtues, or others based on collections of popular proverbs or allegories; and of course scores of Bible-themed series. Albrecht Dürer, the brilliant Northern Renaissance man, was first among the great European artists to exploit publishing and printmaking.

Dürer’s Apocalypse series (1498) was the first printed book in Europe to be illustrated and published by an artist, and it captures the zeitgeist of Europe on the cusp of the sixteenth century — a time that according to enthusiastic millenarians would signal the end of the world as described in John’s hallucinatory visions recorded in the Bible book of Revelation. Dürer’s Apocalypse series proved remarkably popular — no doubt owing both to its artistic merit and apposite subject matter.

* Printing Images in Antwerp, p. 97

In a letter dated August 1509, Dürer wrote that printmakng was far more lucrative than painting: ‘In one year, I can make a pile of common pictures…. One can earn something on these. But assiduous, hair-splitting labor gives little in return. That’s why I am going to devote myself to my engraving. And had I done so earlier, I would be today one thousand florins richer.’* And engravings demanded higher prices than woodcuts; for example, Dürer’s Passion engravings sold for four times the price of the similar woodcut versions.

Albrecht Dürer’s Triumphal Arch, 1517. Image: The Met

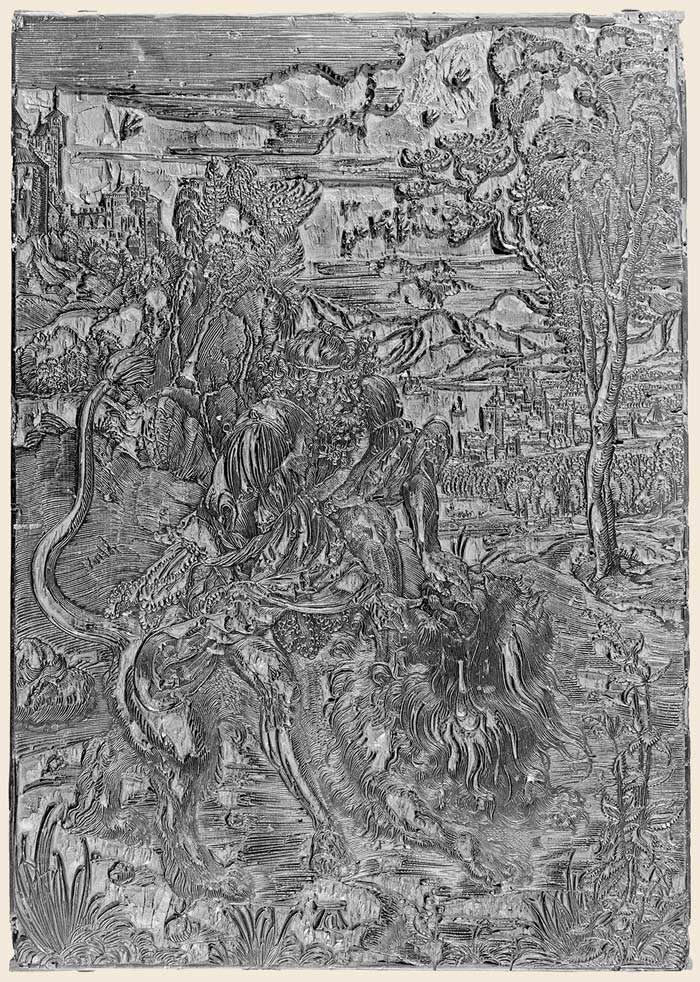

Dürer was also responsible for creating one of the largest woodcuts ever made. His gargantuan Triumphal Arch printed in 1517, a propaganda piece commissioned by Emperor Maximilian I, measures approximately 3.6 m × 3 m (12 × 10ft) and was printed onto 36 sheets of paper from 195 woodblocks.

Pirates & Copycats

Besides numerous talented artists, a whole host of lesser copyists (we might today simply call them plagiarists) realized how easy it was, and with a bare minimum of talent, to make passable copies of works by the likes of of Dürer, Michelangelo, or Raphael. Hardly any skill is required to trace a print onto a new copper plate or woodblock. And then one only need learn how to use woodcarving tools or an engraver’s burin to make cheap copies. Briefly imprisoned by the pope for producing a set of sexually explicit engravings, Marcantonio Raimondi, in addition to authorized collaborations with the likes of Raphael, copied the best works of other notable artists. Raimondi was an exceptionally skilled engraver (he and Raphael established a school for engraving) and he was not a clandestine copycat; he made no secret of his copying the works of great artists and selling them for profit. He eventually came to blows with Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), whose work he freely and unabashedly copied. Dürer was unimpressed and, according to the sixteenth-century art historian Giorgio Vasari, in 1506 Dürer brought a lawsuit against Raimondi and his Venetian publisher, the Dal Jesus family.

By the middle of the sixteenth century printmaking was a burgeoning industry producing millions of prints throughout Europe. And it was not only Italy and Germany that had cornered the market. One of the most important printmakers of the century hailed from Antwerp.

The Four Winds

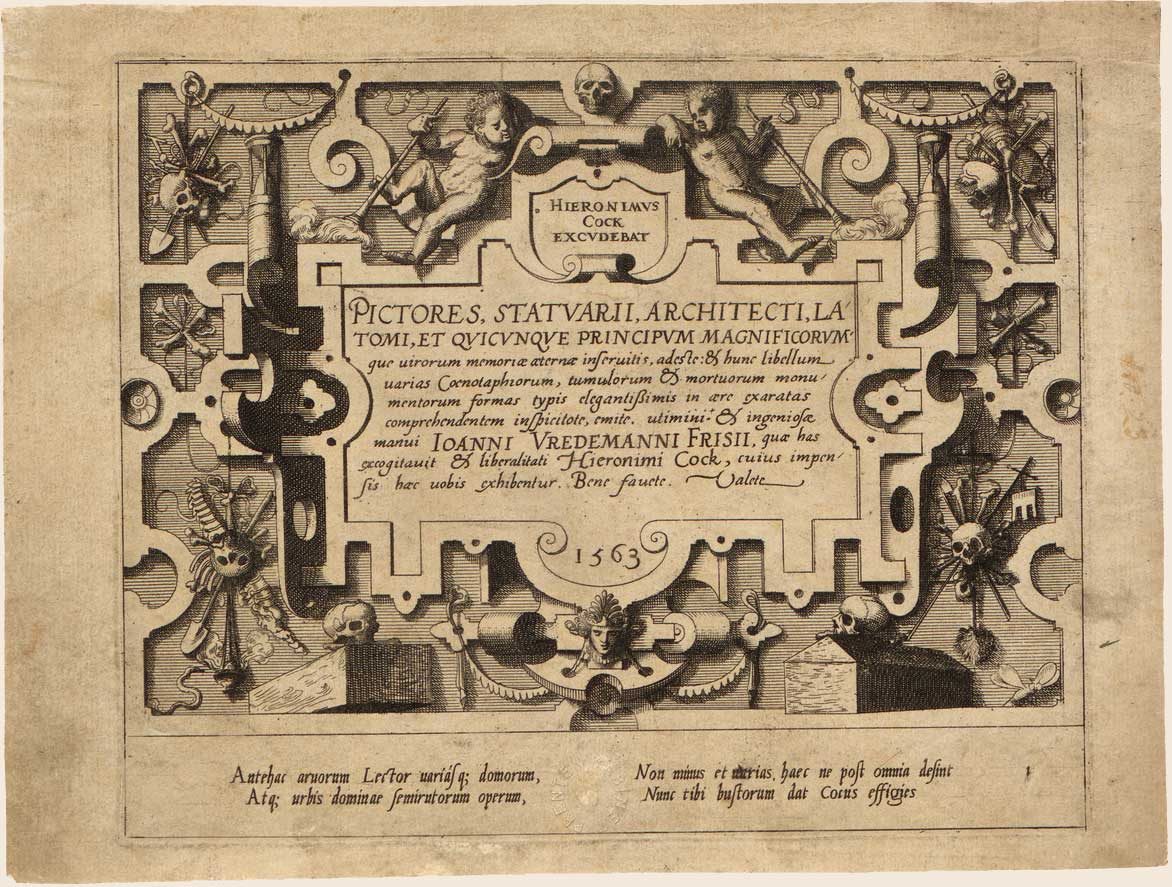

It was not artists alone who popularized printmaking, but a new kind of printmaking publisher. One of the most notable sixteenth-century firms was the Antwerp husband and wife team of Hieronymus Cock and Volcxken Diericx. Although Cock was an artist, he concentrated on finding and publishing the work of both upcoming and established artists. They collaborated with none other than Hieronymus Bosch and were among the first to recognize the brilliant talent of Pieter Bruegel, who supplied the firm with upwards of sixty designs.

During the last decades of the sixteenth century, their printshop, Aux Quatre Vents (At the Sign of the Four Winds), was arguably the most important in Europe. When Cock died in 1570, Volcxken continued to successfully run the business for another thirty years. Between 1548 and 1600 the printshop of Hieronymus Cock and Volcxken Diericx produced some 2,000 prints in many tens of thousands of copies.

From Prophets to Porn

The sixteenth century world went through quite a profound transformation. The Reformation in Europe, the first sustained challenge to Catholic orthodoxy in a thousand years; the ‘discovery’ of the New World, technological advancements, progress in the sciences, in commerce and international trade, rapid urbanization, expansion of formal education and universities. This is the very same era in which printmaking and a renewed popular interest in art flourished.

Jupiter and Semele ‘embracing’, engraved by Marco Dente, c. 1515–27. Image: The Met

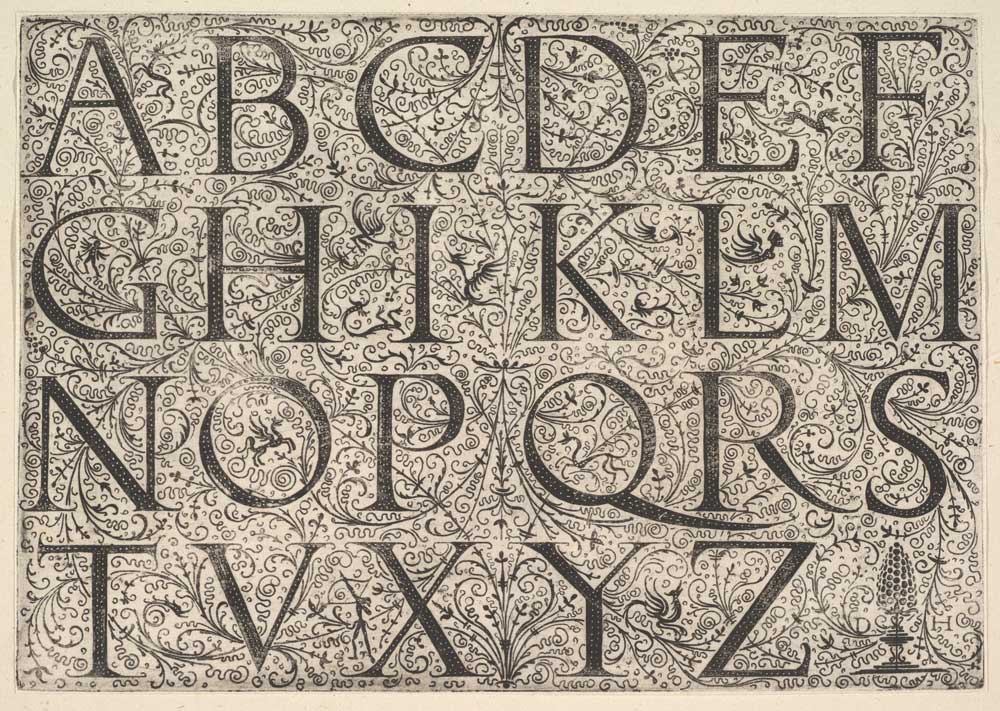

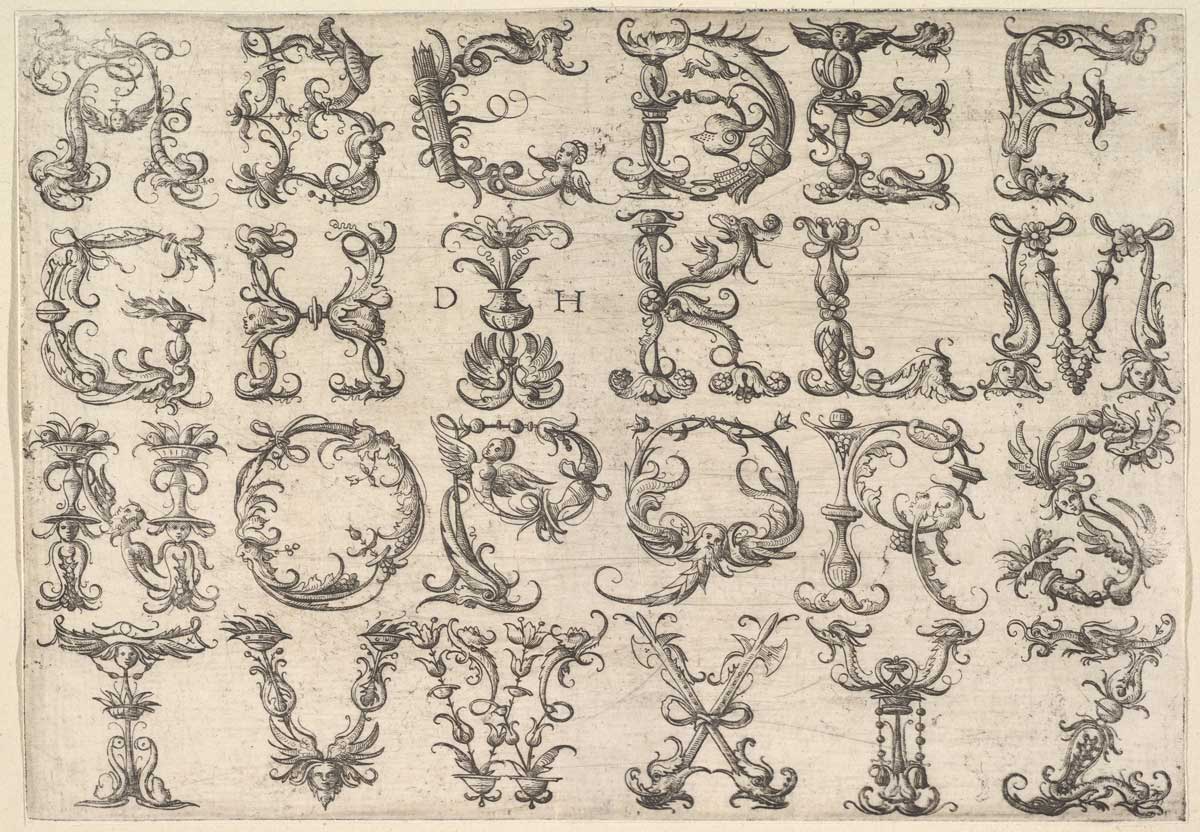

The Renaissance had a love affair with classical antiquity, resurrecting and re-purposing its iconography, art, architecture, and literature — even its letters, the classical Roman capitals. And slowly we witness a cautious shift away from Jesus, saints, and prophets to pastoral landscapes, scenes of everyday day, of people eating and drinking, dancing and marrying, and even erotica. Marcantonio Raimondi, who so brilliantly transformed Raphael’s work into engravings, is responsible for both some of the most profoundly religious and sexually explicit prints of the Renaissance.

If you were a producer of prints designed to titillate and arouse, then you were safer off borrowing from Greco-Roman mythology. Two random naked figures having sex was terribly licentious — scandalous even; but Jupiter fucking Venus — that was art; and what’s more, it was art made by pagans before Jesus, so they didn’t know any better! — a well-worn argument that’s at least as old as Saint Augustine and used by humanists and others to reconcile their love of pagan literature and art with their Christianity.

For Art’s Sake

Related articles

▸ From Farting to Fornication

▸ Botticelli & the Typographers

▸ Renaissance Metal

▸ The First Illustrated Books

Just as the printing press brought knowledge and books to the entire world, so printmaking introduced the broader world to art. These days, when we’re permanently immersed in photos and videos, it’s hard to grasp just how important and revolutionary printing and printmaking were. Today, it’s as easy for me to look at a photo of bison painted on cave walls 40,000 years ago as it is to study the minutest details of a fifteenth-century Dürer woodcut, a sixteenth-century Bosch or Bruegel engraving, or a seventeenth-century Rembrandt etching. How lucky we are. ◉

ILT is made possible by the generous sponsorship of Positype, & the support of these friends.