Deodorant changed Kervin Brisseaux’s world.

We’ll get to the Why exactly, but first the Where: I’m chatting to the digital artist in LA, where Kervin is hosting sessions creating on the iPad at Adobe creative conference MAX 2019.

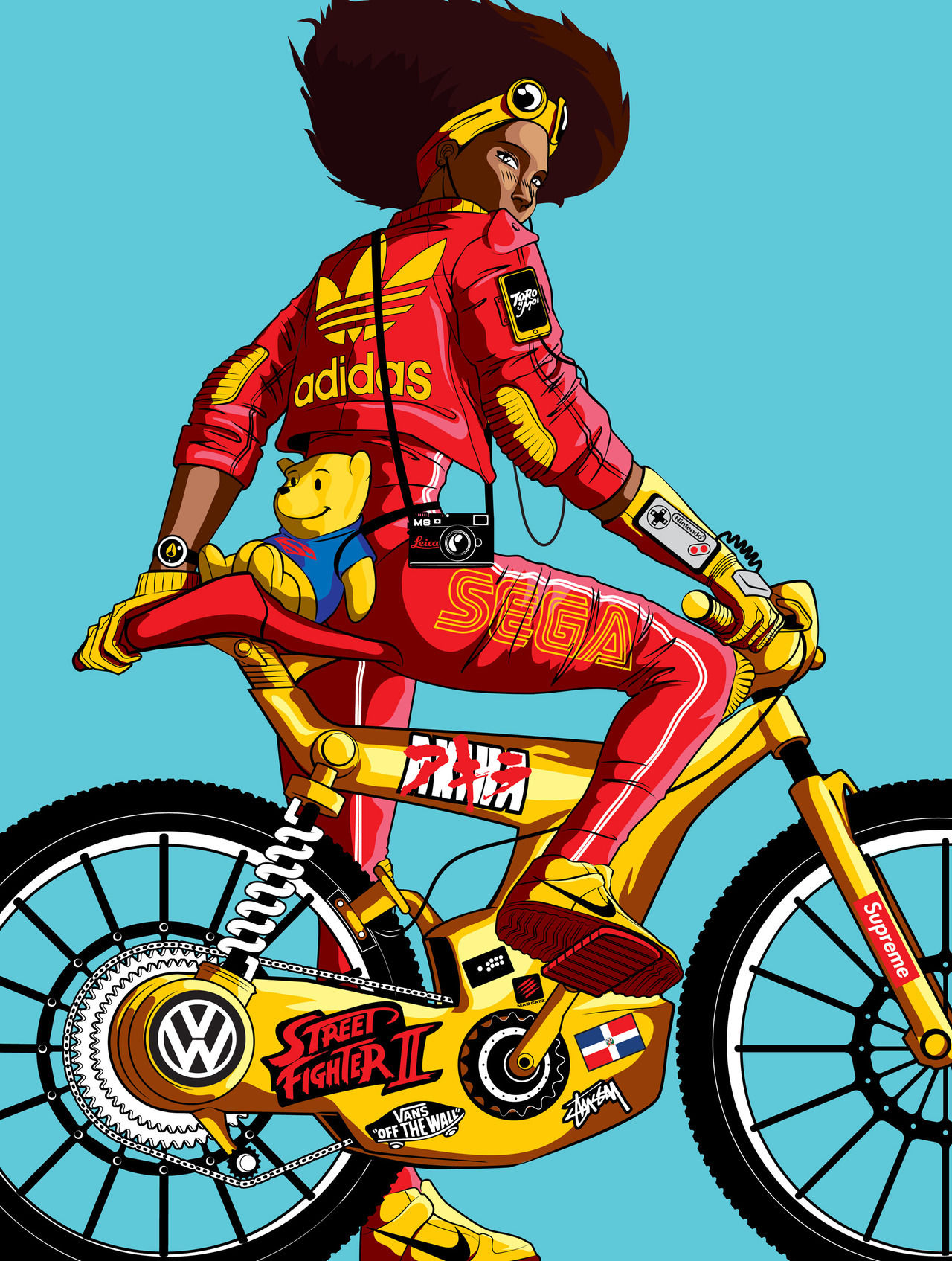

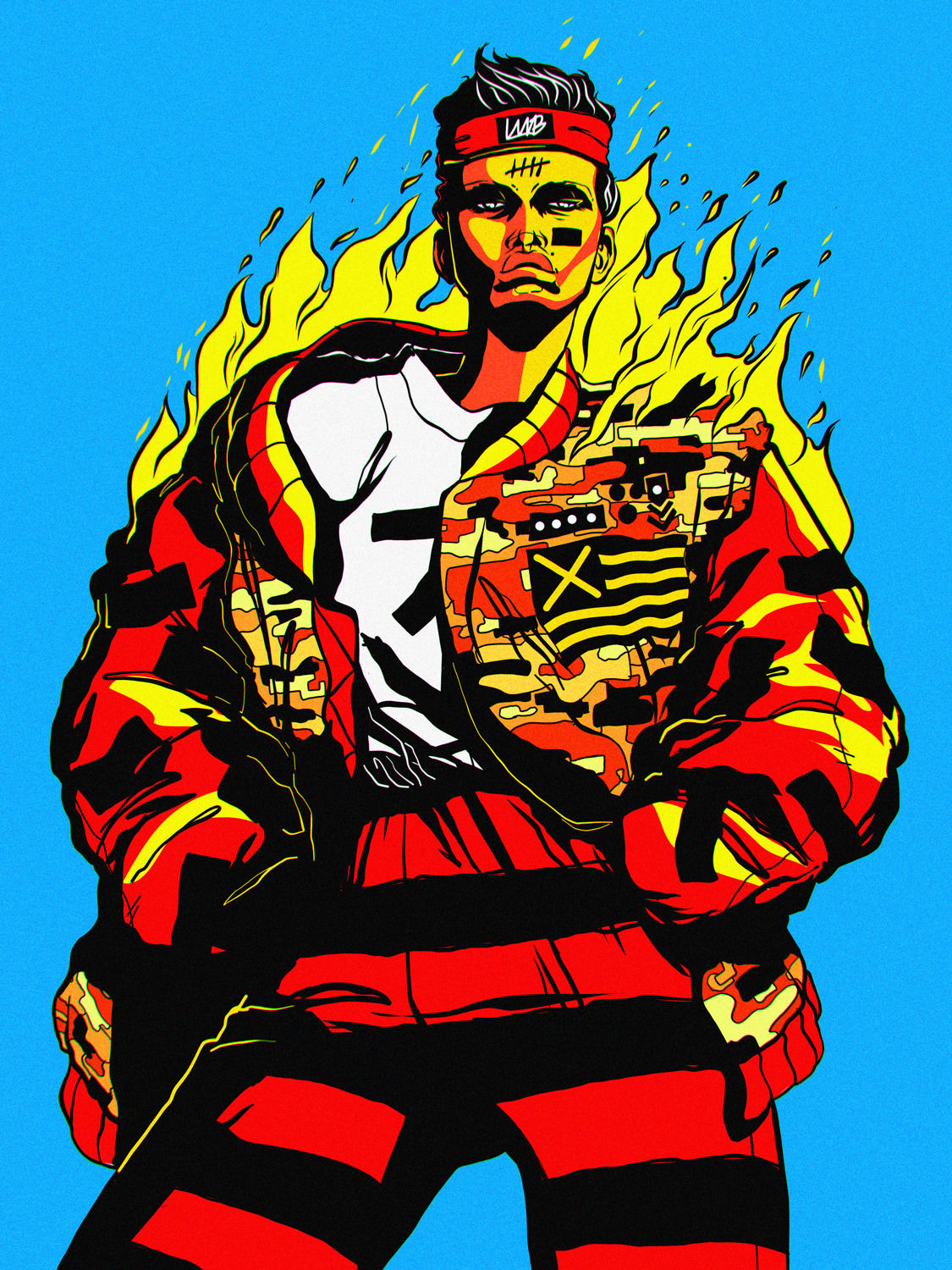

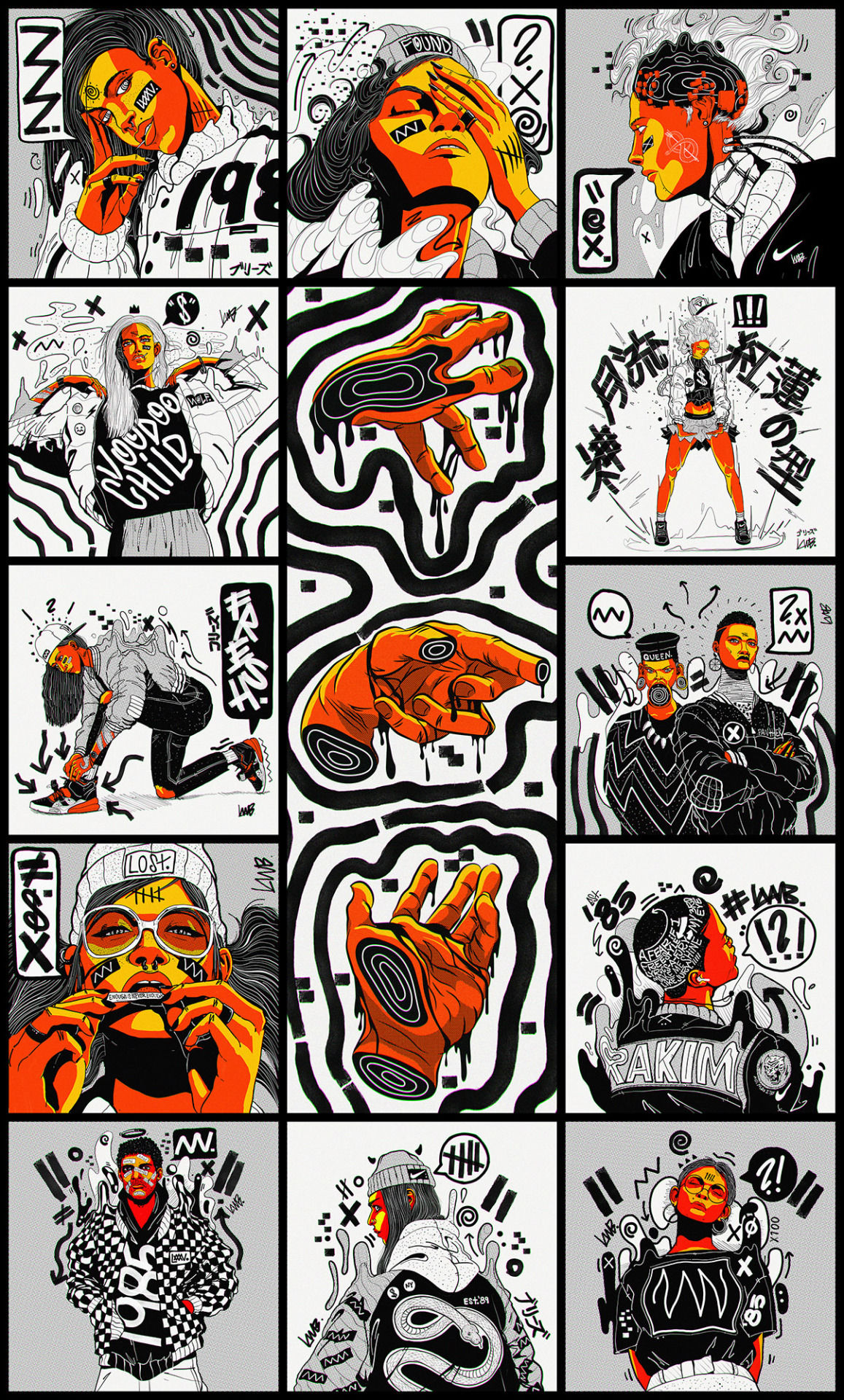

All those sessions are fully booked, such is his popularity. Kervin made his name across the 2010s with vector figures that felt both futuristic and as fine as Greek Gods. He also found acclaimn making popular tutorials for us, adapting his style into a ‘doodle bomber’ fashion – and as design director for the NY/London-based Vault49 agency.

But how did deodorant play a part in this journey? And what made him ditch architecture for art? Find out the A to Z of Kervin Brisseaux in this interview with the constantly evolving New Yorker.

A is for Adobe. It’s also for Architecture, which you originally studied. How did you go from that to Art?

“The short answer of it is, I was more interested in illustration than architecture. But I wasn’t truly honest with myself about that until maybe into my graduate year of studies.

“So, to backtrack a little bit: I grew up in an immigrant household. Haitian American, right? Haitian parents. Very strict influence, in terms of what the expectations were for me. Especially growing up in America.

“They moved in the mid ’80s. I was born maybe two years after that. 1985. And their goal was just for a better life.

“Fast forward to up about high school. I’m feeling the pressure of, ‘Okay, crap, I need to become either a doctor, lawyer, engineer.’ But I just didn’t have an interest in it. And it really showed. I just did not care. And I had to find a middle ground to appease my parents, because I did want to make them happy. But then, still scratch that itch of creativity.

“I was always drawing, doing something. And I didn’t understand what that meant, in terms of a profession. Like, the word ‘graphic designer’ wasn’t in my vocabulary until maybe college. I didn’t know that was a thing. And then, I was like, ‘Well, what’s that?’ And once I learned that that was an option, I felt this fear I guess, while always wanting my parents’ approval. So, it was like, architecture was definitely a way to get that approval. Because it was a very distinguished profession. But you also have to be passionate about that journey, and once I realised that it would take 10 years or whatever to be able to become a licensed architect, being around 30 after graduating to get my license, it made me ask myself, ‘Is this something that I actually really care about that much to go for an additional 10 years of suffering to do?’ Right?

“Illustration came into the journey around grad school. I was still doing architecture and I was finding my niche, focusing more on the graphic element of architecture and not so much the structure science. The theory was okay, as well. But I was really gravitating towards how to present the work. How to make it sexy. How do you really convince people from the initial reactions, the visceral response you get from seeing it up on the wall. That’s what I liked most.”

Was architecture ever sexy for you? Like the cities and buildings seen in comic books, animation?

“Absolutely. Look at concept art. Akira is a great example, because of the matte paintings that would appear for seconds in the film. You just freeze frame that and that’s enough to be a poster for a room. Or a mural in a museum.

“That’s what makes you believe that the world is tangible and real. It’s so incredible the detail that they put into a frame that would only exist for a couple of seconds on the scene.

“I actually gravitated towards architects that follow that aesthetic. Like, one architect that I was inspired by later in the game when I was still studying was Neil Denari, his illustrations. I say illustrations, because that’s what it looked like to me. They were architectural drawings, but they balanced 3D mediums, and 2D hand drawings. They look very manga, anime, comic book, because of the detail, the harsh contrasts of the shadows that he would incorporate in his sectional drawings.”

How did you get into illustration?

“So, I did undergrad in Catholic University of America in D.C., which was for architecture, specifically. And then, I got into Syracuse grad school in upstate New York to continue my studies. And maybe that second year was when I went into my first freelance gig, for AXE Body Spray, of all things.

“They were telling me what the budget was, what the scope was, and I realised I could be doing this for a living, comfortably, and still be doing what I enjoy doing anyways.

“I didn’t get the gig, because I was still so wet behind the ears in terms of graphic design, understanding commercial art communication. I was formally trained in architecture not graphic design, so it took some time. The jargon, I did not understand back then, because it was just so new to me.”

Do you think young creatives were automatically alienated by such jargon?

“Even today, I don’t think they really realise the possibilities. At least, they don’t have the technical literacy to be able to dive headfirst into those interests. So, what I mean by that is, back then, not knowing the options of design is one thing. But then, compound that today with the daunting task of being able to understand softwares, the technologies that are ever evolving. It’s crazy.”

“So, for me, my special focus is, trying to enlighten kids from rougher neighbourhoods, or, just neighbourhoods that don’t have that kind of accessibility to those products or those program options. The stigma that I grew up with was, kids in my hood, or kids from particular zip codes, seemed like, if you weren’t able to have the intelligence or the goal to strive for those professions of doctor, lawyer, and engineer to appease the parents, the other option would be to either go for music or sports. Or, the worst thing, which is get involved with not so great, illegal lifestyles. Because that’s just the trap that they’re in.

“Creativity was like a foreign object to me. It was just something that you did at home just to pass the time. Not something that you would necessarily pursue as a career. And so, how that changes today is, maybe they might be slightly more aware of it. But the knowledge that comes into what does it actually mean to be a graphic designer, what does it mean in terms of a career choice? What are the paths you can take? I think kids today still don’t really know, especially those kids in the same neighbourhoods that realise that it’s not an option.

“Enlightenment starts by going in at the ground level. Now, you could introduce them in the university stage, which is, that’s normally an option. But I think it should start much sooner, because a lot of times, especially when they’re applying for schools, they don’t really know what to go for. And those kids that go in undefined, probably realise almost a little too late, ‘Hey, graphic design could have been a way to go.’ Or, illustration, or fine art.'”

How do you enlighten these kids?

“With Vault49, we get to work very closely with the Shawn Carter Foundation. And that’s through Lawrence Lartey from UAL, who created a project where he wants to bring kids from rougher zip codes of London and the rougher zip codes of NYC and they come together. They don’t need to have design backgrounds. They just need to have a curiosity for learning.

“It’s about 10 kids total from across the world. And they get to visit each other’s cities. So, these kids who would never even think of being able to travel, they’re now able to go across the pond and experience a whole new culture. And that informs their whole design process.

“They’re given a brief, typically by a real client. A couple years ago, we did something with Ford. And Ford gave them a project about how do they take their logo and kind of revitalise it and utilise it in ways to make it more appealing to a particularly young demographic. So, they came up with this whole merchandising campaign, as well as a few activations, and all within a span of two weeks.

“That has now also spanned into My Brother’s Keeper, which Obama administration’s founded, based in Boston. And we’ve done something similar with them, but more ‘hardboiled’ things. Like, last year’s focus was gang violence, and how do you create a program that kind of shines a light on gang violence, using graphic design. And what are some kinds of activations you can do to bridge the gap or create a means of communication between parties that could get into that lifestyle, and maybe shine a knowledge of them through design by hopefully maybe changing their ways. Or, at least giving them a chance to take pause and think about the choices that they’re making.”

How did you end up at Vault49? What was the journey from potential architect to design director?

“Oh, man, so, it was a bit wild. Even though my professional literacy of graphic design was nonexistent, my understanding of digital softwares happened quite early actually. I got into digital software maybe before the end of my high school career. I was introduced to Photo Deluxe and whatnot. And then, when I saw digital art and I saw that being used for online forums – do you remember those? Where people would do avatars, or little tags to put on the base of whatever you post?

Yeah. Back in the late 90s to mid-2000s.

“Before social media was even a thing, we had those forums. And there’d be forums for all types of stuff. Street Fighter had one. There was a forum called Tagmonkey, which was dedicated to people who would create tags, which were literally just little rectangular boxes of art that would exist underneath every which post. And you would ‘commission’ artists to make them. I mean, we wouldn’t do it for money, it was more for street cred, really.

“It was in the same way how you would tag the side of a building. The equivalency, in my eyes, to that was what these kids were doing with digital art on those forums. And so, that was my foray into digital art.

“Jumping a couple years after I discovered an art collective called Depthcore, which is run by a guy named Justin Maller. What he was doing was collecting a bunch of like-minded individuals to create artwork at a larger scale to release to the public. Kind of what we get nowadays in social media, but we didn’t have that. All we had back then was DeviantArt. And then, DeviantArt was already oversaturated with digital executions. Back then, like, this was like 2004 or ’05 when I discovered them. And when I joined, in 2006, that got me into understanding the multitude of different mediums that digital art can go into. It doesn’t have to exist just in these small little squares. Like, the world becomes much bigger now when you’re seeing other people doing what they’re doing.

“My graphic design education was through that collective. For better or worse, that’s where I learned the ins and outs of digital art and what it meant to me. For my undergrad all the way through to grad school, I was doing stuff for them. So, I studied architecture eight years. I discovered Depthcore maybe the last six years of my pedagogy. I was getting more into freelance at the time, which wasn’t much, but working with actual clients was teaching me another thing about the profession, as well.”

How many people were in that collective over the years?

“Over the years, I think we definitely got over 100 members. I think actively, at one time, there was no more than maybe 30 members.”

“Some people were already studying graphic design. Some of them were artists that jumped into digital. Some of them were just child prodigies. They were 13 year olds that were just whiz kids at the softwares that they were using. And because it was still fairly new, there wasn’t really much of a litmus test, as in terms of what was actually good or bad.

“We had our own opinions of it. But because the industry wasn’t oversaturated yet, in terms of digital art, especially abstract art, we were setting our own guard rails and figuring out what qualified as good work. And obviously, that conversation has evolved because it’s just so accessible now. But back then, you see the trajectory of where digital art was back then to where it is now. The conversation is way more diverse. It’s so many different languages now.”

How was life after Depthcore?

“I spent a year looking for architecture work. And then, I spent a month redoing my portfolio, making it more commercial, catering to an avenue that people find interesting overall. I then was able to land a few agents to represent me in New York City.

“I was doing like maybe six months of commercial work before I got reached out by a mutual friend of mine, Karan Singh. He was working at Vault at the time, and got me into it.”

In the years since then, you’ve adopted a ‘doodle bomber’ style.

“I’ve gone from like vector to like heavy Photoshopping to 3D. Now, I’m back to doodling, and this was before I even knew Hattie Stewart existed, who’s like my idol now.

“What sparked the idea, I was working with a client. It was a fashion client. And he wanted to come up with some crew neck designs. But I felt so rusty. I didn’t have the confidence to draw figures. So I found some fashion images in Google and mocked up these crew neck designs on there. Posted it on Tumblr, and I was like, ‘Oh. This is getting a decent response. Maybe I should just keep this going.’

“Eventually, it led to some photographic collaborations. Once I got into this, I started doing a bit more research. That’s when I discovered Hattie Stewart and a few other people like that. And I was like, ‘Wow, this an actual movement.’

“And that’s when I kind of rediscovered my passion for comics, anime, and all that stuff. That kind of dripped that into the style that I’m doing now. Plus, I discovered that I actually have an affinity for photography. I really like especially fashion and street photography. I really enjoy it. And now my next step is trying to own that process, as well.

“I’m really just loving the whole mixed media nature of it.”

Read next: Karan Singh on how illustration has taken him from Melbourne to Amsterdam, via New York and Tokyo

https://www.digitalartsonline.co.uk/features/creative-business/kervin-brisseaux-how-i-went-from-deviantart-design-director/