October 3, 2019

John Boardley

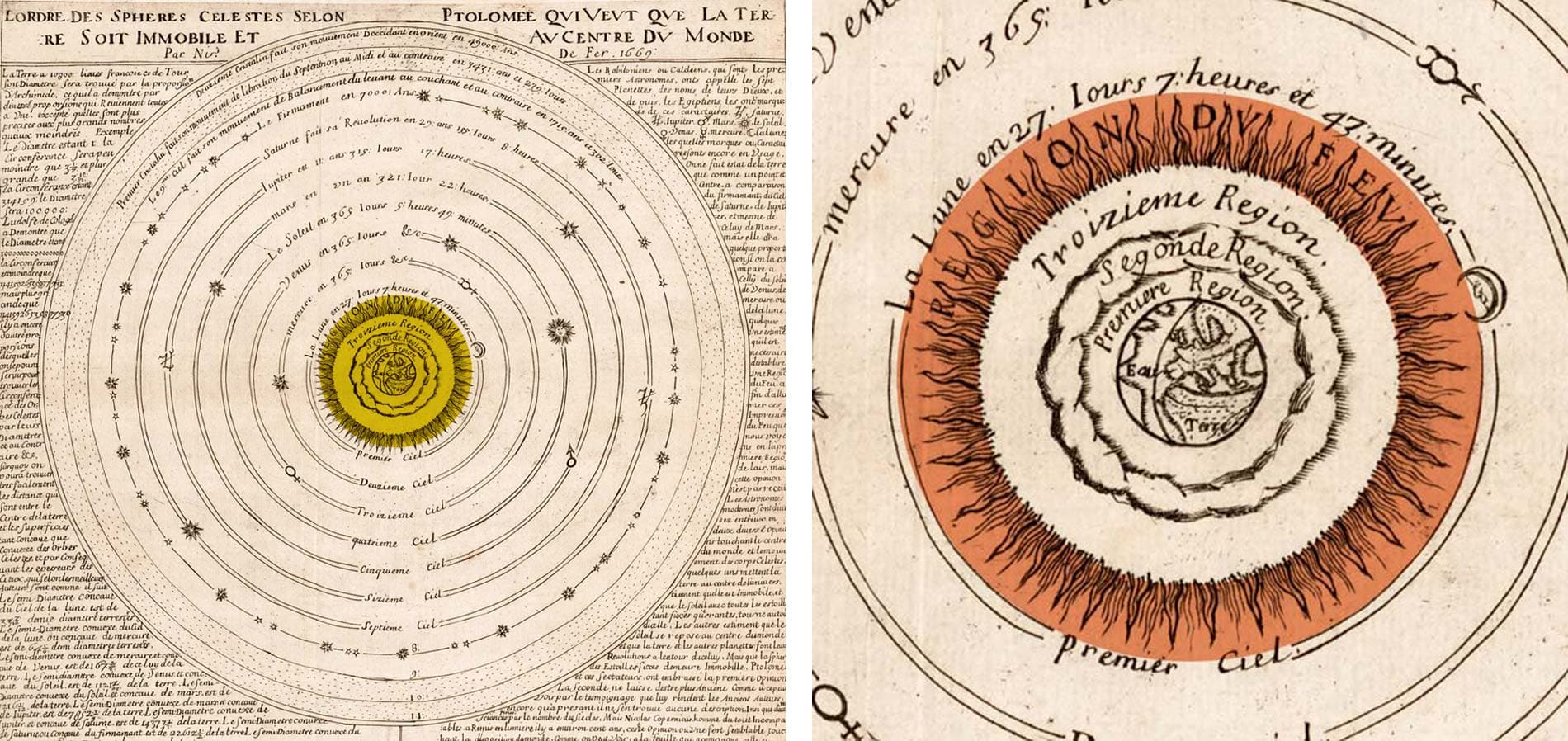

For the best part of 2,000 years, the earth stood immobile at the center of the universe. Surrounded by a series of concentric embedded shells or spheres, one each for the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and an outermost sphere or firmament of fixed stars, for two millennia, the cosmos literally revolved around us. And although Copernicus immediately comes to mind when we think of earth’s change of address, from center of the cosmos to ‘solar satellite’, his theory of a heliocentric, or sun-centered cosmos, was pretty much ignored until the work of Galileo and Kepler in the seventeenth century.

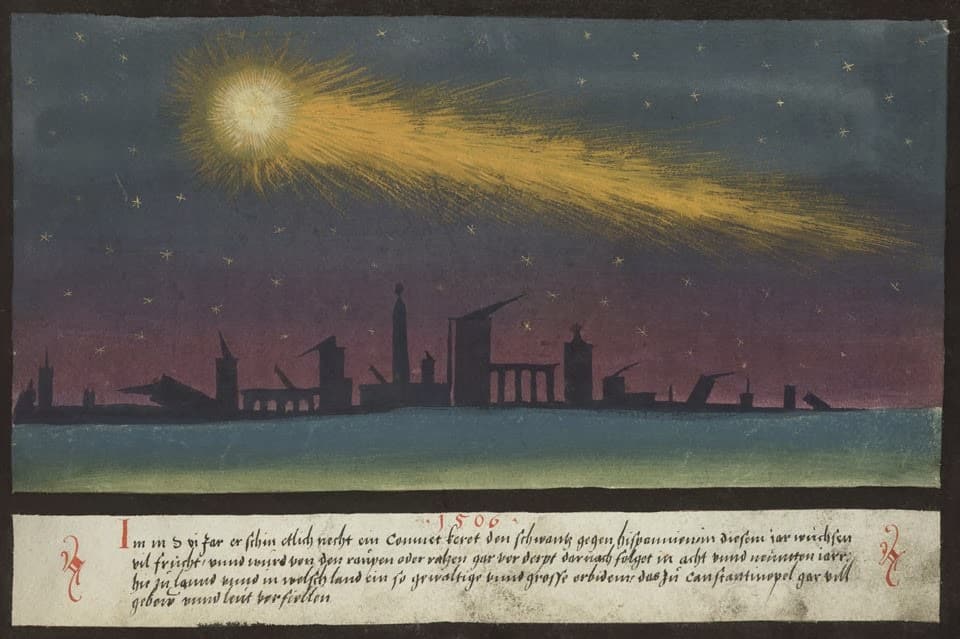

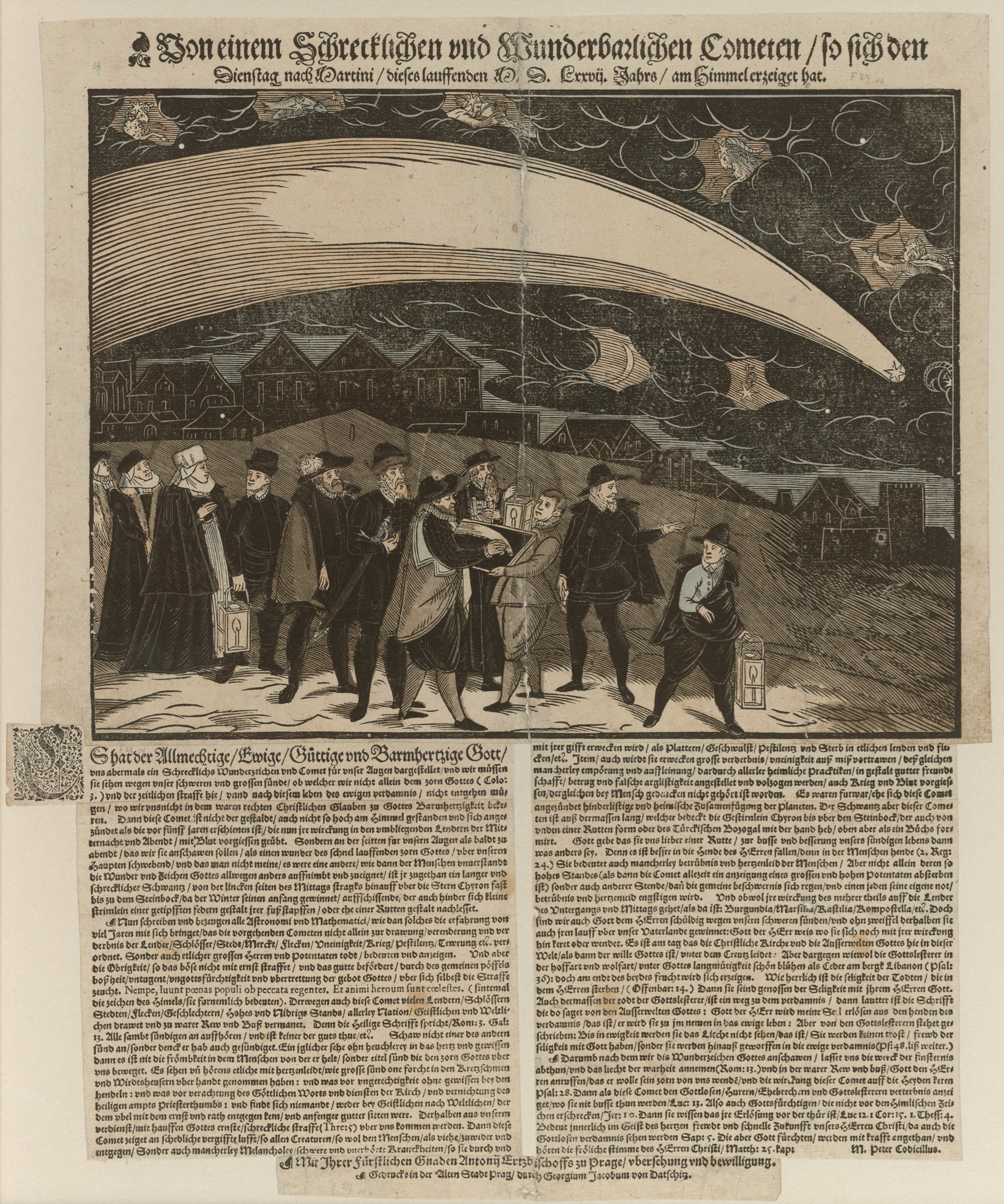

Comets & Cosmic Change

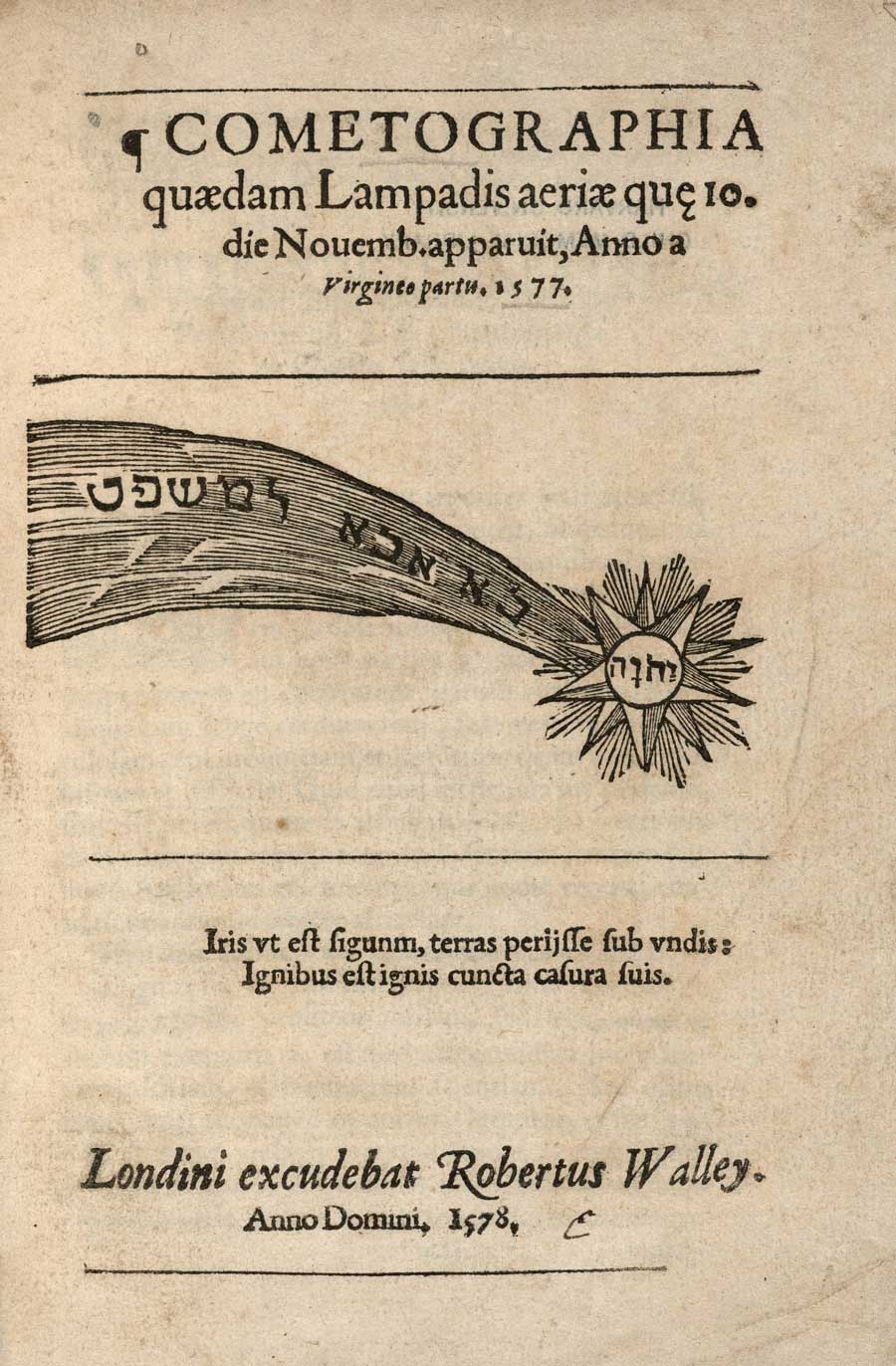

Another lesser-known but nonetheless significant factor in the disavowal of an earth-centered cosmos was an event that occurred in the skies of 1577. First recorded by the inhabitants of Peru, it was thereafter sighted across the globe. In Denmark, Tycho Brahe, the greatest observational astronomer of his age, first saw it on the afternoon of November 13, while out fishing for his supper. He published his cometary theories, based on his extended observations of the 1577 comet, in a book titled, De mundi aetherei recentioribus phaenomenis liber secundus (‘Second Book About Recent Phenomena in the Celestial World’). The Library of Congress has the digitized first edition (1588) available online. By combining observational data from different locations, Tycho was able, through parallax (stuff farther away appears to move more slowly), to determine that the comet was far more distant than the moon.

That was problematic!

According to Aristotle (384–322 BC), the cosmos was perfect, and perfect things don’t change — why would they need to change? They’re perfect! Only the terrestrial region, the earth and its atmosphere was imperfect and corruptible. In short, the cosmos beyond the moon was incapable of change and so comets (new things) could not possibly originate or exist there. Therefore, at least since Aristotle, comets, along with the milky way and shooting stars, were considered terrestrial or meteorological phenomena – just like the weather. Logically, they could hardly be anything but!

For Aristotle, comets were a special kind of long-burning shooting star caused by a combination of rising warm, dry air and the friction caused by the rotating celestial sphere (that carried the moon) against the elemental fire in the upper region of earth’s atmosphere, or to quote Aristotle in his Meteorology, “so whenever the circular motion stirs this stuff up, in any way, it bursts into flames.” If you’re having a hard time picturing that, then imagine that the earth is at the center of a glass or crystal sphere – and as that sphere rotates around earth, the friction between it and the earth’s upper (and fiery) atmosphere, produces comets.

Even before Tycho, the German doctor and astrologer Helisaeus Roeslin (1545–1616) had been among the first to determine that the comet of 1577 was absolutely not a meteorological phenomenon. In his book of 1578, Theoria nova coelestium meteoron, he placed it beyond the moon, thus shattering Aristotles crystal balls and toppling Aristotelian cosmology. He also predicted the end of the world in 1642 – needless to say, his scientific predictions proved more reliable than his eschatological prognostications.

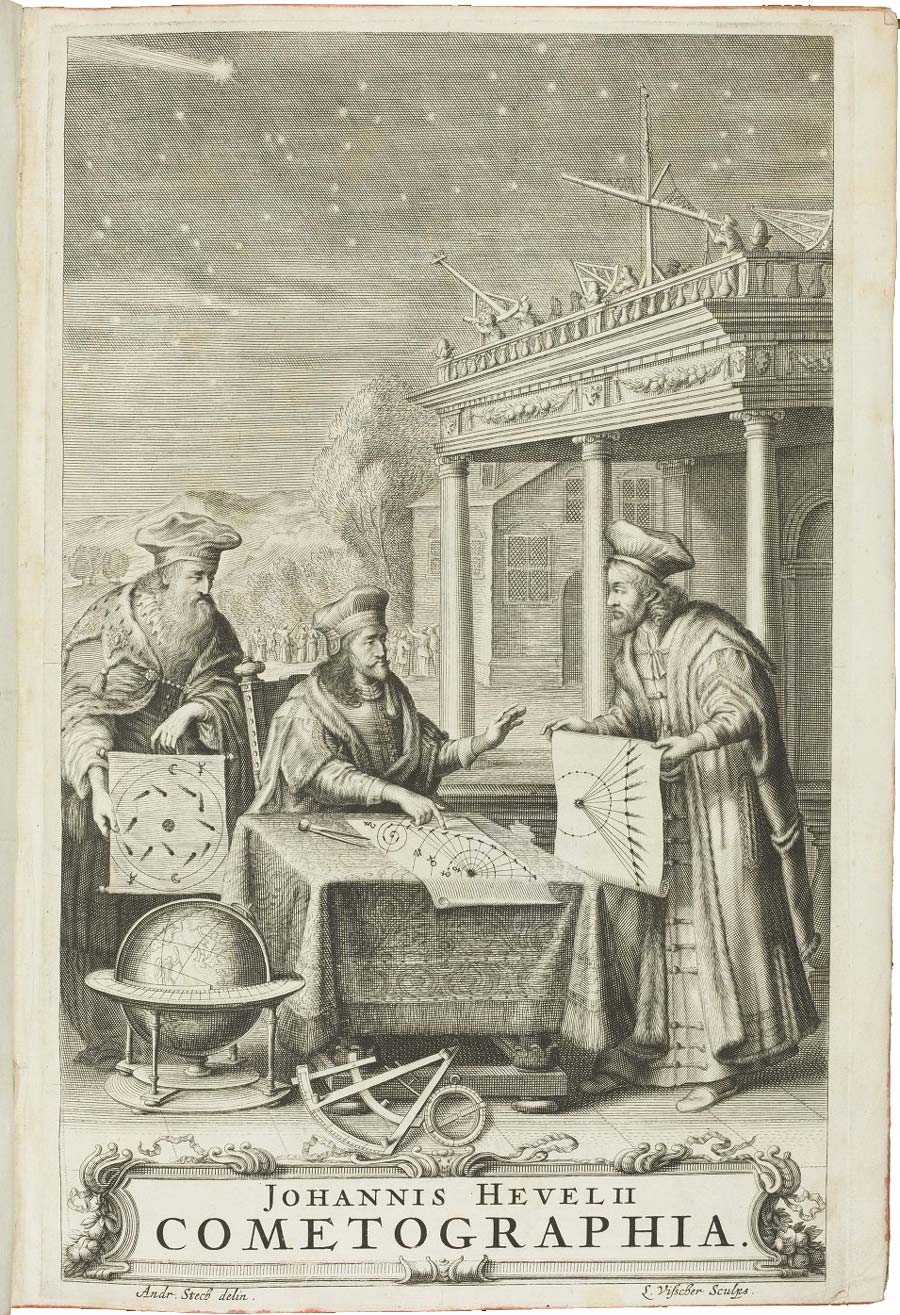

In the next century, comets would become the most controversial topic in astronomy, with print proving instrumental in the wide dissemination of new theories that, ultimately, transformed our understanding of — and place within — the cosmos.

Long-haired Stars

The word comet is derived from the Greek κομήτης (kometes) meaning to wear the hair long, thus a comet is a long-haired star. Not until the late seventeenth century, with the work of John Flamsteed and Isaac Newton, would significant progress be made in determining the nature of these unusually hairy ‘stars’. But even by Newton’s time, no one really had any idea what comets were made of. Voltaire argued that the tail of a comet was smoke from its being set alight from its close proximity to the sun; Newton, on the other hand, claimed the tail to be made up of highly rarified vapors. There still was a great deal to be learned. Only much later, in the 1950s in fact, thanks to the work of astronomer Fred Whipple, was it determined that comets were fast-moving dirty snowballs.

Encore?

If you’re wondering whether the the Great Comet of 1577 will ever return to our skies, then the answer is almost certainly no. Unlike Halley’s Comet, it is designated as a C-class, or non-periodic comet and, as of now, according to my arithmetic, it’s about 50 billion km from earth, deep into interstellar space, and more than twice the distance from earth as Voyager 1, that left home exactly 400 years later, in 1977. ☄