If you’ve been online in the past week, you’ve probably seen one or two headlines about the European Union voting in favor of easy-to-replace batteries in smartphones by around 2027. That’s based on a June 14th vote in which the European Parliament voted overwhelmingly in favor of an agreement that would overhaul the rules around batteries in the bloc.

The good news is that those headlines are fundamentally accurate; the EU is moving forward with regulation designed to require smartphones to have batteries that are easier to replace, to the benefit of the environment and end users. But this being the European Union, there’s a lot more going on behind the scenes. And it’s these details that could have a significant impact on how and when manufacturers will actually have to comply.

For starters, the widely cited 2027 deadline for offering smartphones with more easily replaceable batteries isn’t quite the whole story, according to Cristina Ganapini, coordinator of Right to Repair Europe. That’s because there’s another piece of legislation currently working its way through the EU’s lawmaking process called the Ecodesign for Smartphones and Tablets. It contains similar rules about making smartphone batteries easier to replace and is expected to come into effect earlier in June or July 2025. So by the time 2027 rolls around, some smartphone manufacturers may have already been selling devices with user-replaceable batteries in the EU for over a year.

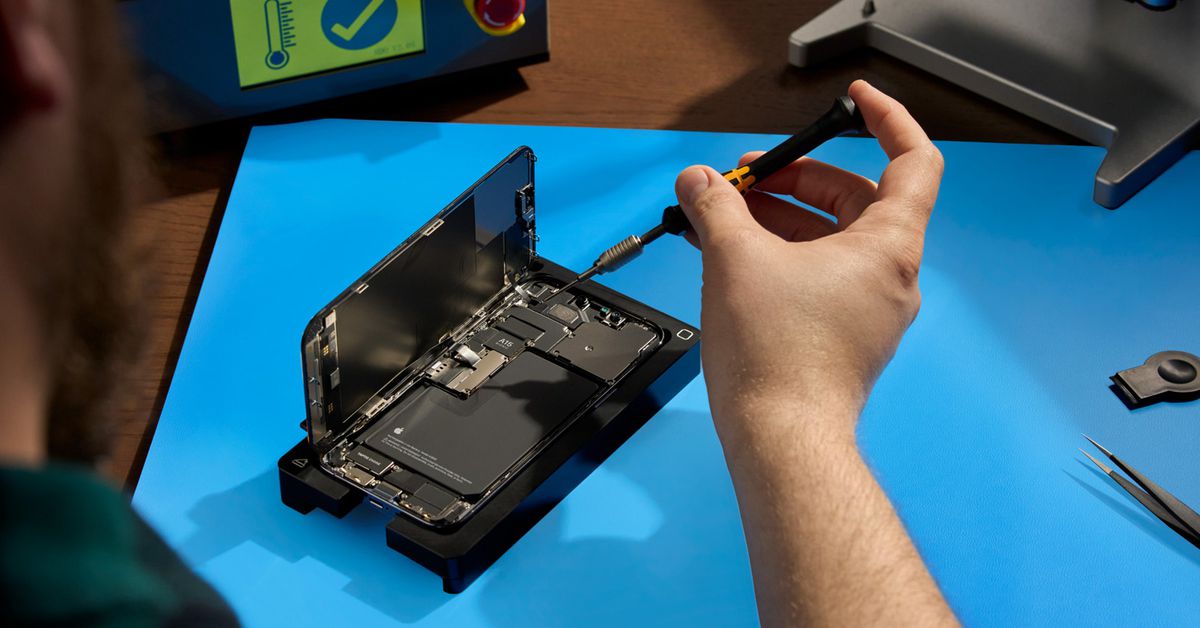

a:hover]:text-gray-63 [&>a:hover]:shadow-underline-black dark:[&>a:hover]:text-gray-bd dark:[&>a:hover]:shadow-underline-gray [&>a]:shadow-underline-gray-63 dark:[&>a]:text-gray-bd dark:[&>a]:shadow-underline-gray”>Photo by Owen Grove / The Verge

According to a draft version of the ecodesign regulation on the EU’s website, batteries should be replaceable “with no tool, a tool or set of tools that is supplied with the product or spare part, or basic tools.” It also says that spare parts should be available for up to seven years after a phone’s release, and, perhaps most importantly, “the process for replacement shall be able to be carried out by a layman.” The legislation is currently being scrutinized by the European Parliament and Council, and Ganapini expects it to pass into law in September this year, with its smartphone battery replaceability requirements coming into effect a year and a half later.

Despite the overlap between the two pieces of legislation, the battery regulation voted on by the European Parliament this month is still important. That’s because the battery regulation is more stringent than the ecodesign regulation in a key way: it doesn’t offer a loophole that would allow smartphone manufacturers to avoid having to make their batteries easy to replace if they’re able to make them long-lasting instead. Specifically, they’ll need to maintain 83 percent of their capacity after 500 cycles and 80 percent after 1000 cycles to qualify. Such devices would also have to be “dust tight and protected against immersion in water up to one meter depth for a minimum of 30 minutes,” according to the ecodesign rules — capabilities often achieved with glue.

“We would rather have seen longevity requirements alongside repairability requirements rather than leaving the trade-off to manufacturers,” says iFixit’s repair policy engineer Thomas Opsomer. “That said, 83 percent capacity after 500 cycles and 80 percent capacity after 1000 cycles is a fairly ambitious requirement; it would probably translate to at least five years of use.”

“A portable battery should be considered to be removable by the end-user when it can be removed with the use of commercially available tools”

It’s unclear exactly how many manufacturers’ smartphone batteries may meet the requirements for this longevity loophole. For example, one Apple support page notes that a “normal battery” typically retains up to 80 percent of its original capacity after 500 complete charge cycles. But other manufacturers may already be providing batteries that are this long-lasting. Fairphone spokesperson Anna Jopp tells me the (fully replaceable) battery in its Fairphone 4 already fulfills these longevity requirements, while Oppo recently boasted that some of its batteries retain 80 percent of their charge after as much as 1,600 charge cycles.

In addition to not offering the longevity loophole, Opsomer also points out that the battery regulation covers all products with a portable battery; it’s far wider-reaching than the phone and tablet-focused ecodesign regulation.

So what exactly does it mean for a smartphone’s battery to be easy to replace? A lot of the EU’s definition boils down to what tools are required for the procedure. Although “removable” recalls the feature phone era or one of Fairphone’s devices that only require a fingernail to open, the definition used in the battery regulation voted on this month doesn’t go that far. Instead of requiring removal without tools, the battery regulation instead places limits on the kinds of tools that will be needed to replace a battery. Here’s the relevant section:

“A portable battery should be considered to be removable by the end-user when it can be removed with the use of commercially available tools and without requiring the use of specialised tools, unless they are provided free of charge, or proprietary tools, thermal energy or solvents to disassemble it.”

Rather than calling for entirely tool-free battery replacement, the wording of the regulation focuses on preventing end users from having to use proprietary tools or finicky processes. So the EU’s goal is less about turning every phone into a Fairphone 4, with its battery you can pop out in a couple of seconds with your bare hands, and more like the recent HMD Nokia G22, whose iFixit battery replacement guide still calls for the use of a basic tool or two. In other words, the G22’s battery can be replaced using commercially available tools that don’t seem terribly specialized and doesn’t require proprietary tools, solvents, or thermal energy like heat guns or an iFixit iOpener, which are designed to melt the glue some manufacturers use to hold components together. Simple, right?

a:hover]:text-gray-63 [&>a:hover]:shadow-underline-black dark:[&>a:hover]:text-gray-bd dark:[&>a:hover]:shadow-underline-gray [&>a]:shadow-underline-gray-63 dark:[&>a]:text-gray-bd dark:[&>a]:shadow-underline-gray”>Image: iFixit

Not so fast, says iFixit’s Opsomer. He points out that while EU law only defines “basic tools, product group specific tools, other commercially available tools, and proprietary tools,” it doesn’t define “specialized tools.” “This current specification could easily give rise to a situation where in order to replace a battery, a user would have to purchase a tool that is in fact specialized but not officially defined as such,” Opsomer says, “The cost of which could easily exceed the cost of the replacement battery.”

So iFixit is pushing for lawmakers to count a device as user-repairable under the battery regulation if it can be repaired using “basic tools.” Included in this category are common screwdriver styles like flat-head, Phillips, and Torx, though Opsomer admits it’s likely to include some nicher implements like iFixit opening picks.

Another potential point of contention is how user-replaceable batteries could coexist with waterproofing. The battery regulation contains an exemption for devices “that are specifically designed to be used, for the majority of the active service of the appliance, in an environment that is regularly subject to splashing water, water streams or water immersion.” Opponents of such rules often bring up waterproofing as a feature that could suffer if a device is designed to be easily opened.

“A big success for the right to repair”

In a statement, Opsomer said the EU’s exemption is based on “unfounded safety claims” and cited underwater flashlights as an example of a device that’s able to offer both a user-replaceable battery alongside a waterproof construction. In a YouTube video, repair technician Louis Rossmann cites the Samsung Galaxy S5 (IP67 — so it can be immersed in relatively shallow water for up to 30 minutes) and Sonim XP10 (IP68 — which can be immersed in deeper water for longer periods of time) as phones with good water resistance that also offer removable batteries, though other recent repairable phones like the Fairphone 4 (IP54 — offering protection against splashing water) and Nokia G22 (IP52 — protected against dripping water) fare less well.

Qualms about the specifics aside, the result of this month’s vote on new battery regulation was broadly welcomed by right-to-repair campaigners. Right to Repair Europe’s Ganapini called it “a big success for the right to repair,” while Fairphone’s legal counsel Ana-Mariya Madzhurova said the regulation “will further empower consumers by ensuring that batteries across industries are more durable, sustainable and repairable.”

The EU’s user-replaceable battery rules still have a long way to go, despite this month’s successful vote. The battery regulation will need to be formally endorsed by the Council of the EU while the ecodesign rules are still being scrutinized by the European Parliament. Although the passage of both sets of rules seems likely given their current progress, discussions are ongoing behind the scenes between different groups vying for looser or stricter interpretations of the written rules.

But, in the years ahead, it’s looking like smartphone buyers in Europe will have a far easier time keeping their devices running and out of the landfill after their batteries degrade naturally over time. And, unless manufacturers want to produce devices with user-replaceable batteries that are only sold in Europe, it seems like the rest of the world is also set to benefit.

https://www.theverge.com/2023/6/24/23771064/european-union-battery-regulation-ecodesign-user-replacable-batteries