For four months in 2018, Danielle Edwards drove past the brownstone on the corner of 6th Avenue and St. Marks in Brooklyn. There was a “For Rent” sign in the window of the second-floor storefront, which caught her eye because the whole facade is enclosed by vintage curved glass.

“I call it the fishbowl,” she says. “I fell in love with it when I first saw it. But I thought, I’m not going to be able to afford that.” Edwards was looking for a new location for her boutique gym, The New Body Project, which claims the distinction of being the only all-women’s boot camp in Brooklyn.

Edwards, 35, started The New Body Project in 2017, after the local women’s gym she worked for shuttered suddenly. For the members — many of them women of color — the gym had been a kind of neighborhood home, and its closure was devastating.

“Literally, a lot of the women had breakdowns,” Edwards recalls. “I just felt like a ton of bricks was falling on me, so I said, I’ve gotta do something.” She decided to start her own gym and went to a number of banks to try to get a loan. It did not go well.

“Even though my credit is good,” she says, “if you haven’t been open for a year, no one wants to look at you — let alone looking at you [if] you’re black and a woman.” So she launched a Kickstarter campaign, and her community rallied to raise $3,000. Still, the location they landed in wasn’t ideal. (“We were doing burpees and there was mold dripping from the ceiling.”) So one day after driving past the fishbowl, she finally called. Just to see. “His original asking price was astronomical, but my community came together,” she says. “We wrote a letter to the landlord and expressed to him how we’re going to build this community, and he dropped the price significantly.”

Even so, it was a stretch. To lock down the space, Edwards had to sell her house that she’d bought in her 20s, when she worked at a bank on Wall Street before getting laid off in the market crash. “I went to the SBA. I was denied. I went to TD bank. I was denied. I went to Capital One. I was denied,” she says. “So I was like, you know what? I have this place in Jersey. I hardly ever go back. I’ll sell that and use the money to secure a new location.”

She did, and for a year, it was wonderful. The New Body Project grew from 12 to 62 dedicated members, and Edwards hired four trainers. Her clients were not the Lululemon-y ladies at boutique studios up the block. They were all shapes and shades, from all different backgrounds, at all different stages in their fitness journeys. From early morning to evening, they could be found barefoot on the big squishy mat in the sunny fishbowl, swinging kettlebells and doing tire squats.

Then COVID-19 hit New York City. “Monday, we were open and doing business as usual, Tuesday I was closing my doors, and Wednesday I was remote teaching a third grader and a sixth grader,” Edwards says. “I was like, wait, what just happened? For nearly a week and a half I just went into the bathroom and cried. I couldn’t process that everything I sacrificed, everything I worked so hard for, could be gone.”

Danielle Edwards instructing at The New Body Project. Image Credit: Sideline.com

A legacy of prejudice, compounded

Minority-owned small businesses stand to be hit the hardest by the pandemic’s economic fallout. In the best of times, entrepreneurs of color face a multitude of unique obstacles, many of which are embodied in Edwards’ experience. Taking straightforward racism out of the equation — of which there is plenty — it’s always difficult to get a loan without already having significant capital behind you. The facts are that the average white family in America has 10 times the wealth of the average black family, and eight times that of the average Hispanic family. In 2019 the SBA found that 49 percent of loans from banks go to white-owned businesses, 23 percent go to Asian-owned businesses, 17 percent undetermined, 7 percent to Hispanic-owned business, 3 percent to black-owned businesses and 1 percent to American Indian-owned businesses.

Because it’s hard to get loans — much less attention and strategic advice — from banks and investors, many minority owners also have more difficulty growing their businesses. In New York City, the virus’s long-standing epicenter, only 2 percent of all small businesses are black-owned, and only 3 percent claim employees (compared to 7 percent of Hispanic-owned businesses, 21 percent of Asian-owned businesses, and 22 percent of white-owned businesses). Many businesses started by entrepreneurs of color also operate in lower income areas, and on narrower margins. In immigrant communities, there are language impediments.

Now those obstacles are compounding at an alarming rate. In the chaotic scramble to disperse the first $350 billion of relief loans from the Small Business Administration (SBA), banks prioritized clients who already have loans with them, as well as “small businesses” that are, in reality, anything but. (See this week’s Shake Shack fiasco.) The SBA had been essentially offering two types of loans: Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL), of up to $2 million (with advances of up to $10,000, dispersed to businesses within three days of applying, but those advances have yet to materialize) and the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), which offers small businesses loans of up to $10 million.

Initial PPP funds ran out last Friday, and last night the Senate passed a new stimulus package that replenished the PPP with another $320 billion — including $60 billion for community banks, credit unions and even smaller lenders like Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs). This last specification is absolutely key to reaching minority small businesses, the vast majority of which have been left out in the cold so far.

CDFIs are some of the only lenders firmly rooted in communities of color, and their inclusion in the PPP is something that Gregg Bishop, New York City’s Commissioner of Small Business Services, has been pushing for. “The overwhelming needs of New York City’s small business community can only be met by the resources of the federal government,” he says. “We fought for more support in the next stimulus and won an additional $60 billion for our CDFIs and local banks. Our smallest businesses who rely on their community partners for support and service now have a greater chance at accessing the capital they need to remain open.”

Hopefully, that money will make it to those who need it most, fast. But in the past three weeks — as banks overlooked small businesses with no safety net — many minority small businesses have already plummeted too far into the red to make it out.

Related: 3 Ways to Support Minority-Owned Businesses

The less you’re asking for, the less likely you are to get it

Back when the first round of SBA stimulus loans were announced in early April, many entrepreneurs were optimistic. James Heyward, a CPA in Durham, North Carolina, certainly was. Heyward is a black business owner, and the majority of his accounting firm’s clients are minority business owners. He spent two days studying the bill and applied for PPP through his bank, Wells Fargo. He didn’t need much to cover his payroll; he was only asking for $5,000. But as the days passed, he just received more emails from Wells Fargo telling him that, in his words, “I was still in the queue, but because of their lending cap, I might need to go apply somewhere else.”

For many entrepreneurs of color, their first obstacle in accessing stimulus funds is that they don’t have loans, a line of credit or an established relationship with a bank. But Heyward is an exception to the rule. He has a fairly extensive relationship with Wells Fargo. He has two business accounts, a line of credit, a business credit card, his personal account, his mortgage and a certificate of deposit. So when he wasn’t getting that little check for $5,000, he started thinking something was off.

“Banks are for-profit businesses, right?” Heyward says. “They’re only making 1 percent interest on these loans. They don’t have the infrastructure for small loans, so their underwriting process for my $5,000 is the same for somebody requesting $500,000. So which one do you think they’ll spend the manpower on? If I was a bank, I would say yeah, okay, I could just give you this money. But it’s better for us to give larger amounts to sure bets than smaller amounts to a whole bunch of risky borrowers. Especially if your business isn’t really open right now. Not to be doom and gloom, but this may cripple you forever, and the bank will be left holding the bag, because I don’t get the sense that they necessarily believe that the government will get the SBA money to them in a timely fashion.”

Heyward isn’t alone in this conclusion. Benjamin Burke is a senior tax consultant at Snappy Tax, in Ocala, Florida. In an email he said, “I have been told off the record that banks are prioritizing the [PPP] loans first for people that have pre-existing loans with them. Then the bigger clients. Then everyone else. Additionally, some banks will not even touch PPP loans under $30,000. If a business owner did not have reserves, it won’t be long before they have to close for good. We are already seeing clients in this position.”

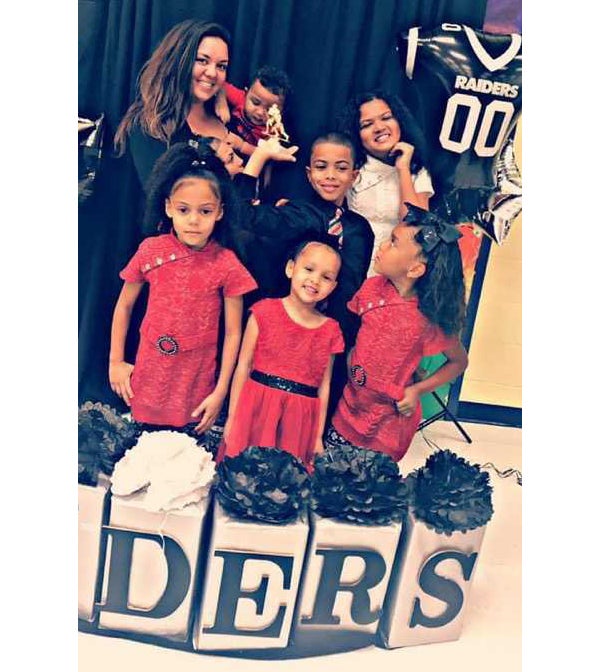

One of Burke’s clients is Brooke McGee, a Latina business owner based in Ocala. A 33-year-old single mom with six kids — one of whom is disabled and severely immunocompromised — McGee worked for a trucking company for 13 years until she got laid off in 2019. So last October she founded her own company, First Watch Dispatch, a carrier, shipping and dispatch service and started out running the business from home. That quickly proved impractical since, as she puts it, “I don’t have a big house in a nice neighborhood, and having 20 semi trucks pull up to my driveway was not conducive.”

She tried to secure a loan for an office space but couldn’t. “So,” she says, “in January I took my life savings and leased a building.” This February, after maxing out her credit card and having the lights turned off in her home, McGee was finally able to pay herself for the first time. Then, the pandemic started to spread, and McGee had no choice but to shut down. Even though her company plays an important role in the supply chain, McGee says a big part of her job is handling truckers’ paperwork, which “has been through literally thousands of hands, at stops from New York all the way to Florida.” The risk to her disabled daughter’s life is simply too great. “I’m trying to work from home,” she says, “but I can’t have the truckers come to my house. Plus I have six kids in six grades and only two computers.”

As of our conversation, McGee had tried for weeks to get through on the government site to file for unemployment. Burke, her tax consultant, has helped her apply for the EIDL and PPP loans through her bank, the Florida Credit Union, but she hasn’t heard back about either. Because McGee’s truckers are all private contractors, her PPP request covers only her salary, and Burke worries the request won’t be worth her bank’s time. “My fear is that these smaller sized loans are being overlooked,” he says plainly. Now, McGee’s landlord is threatening to evict her.

Brooke McGee and her six children. Image Credit: Brooke McGee

Beware predatory practices amidst of information chaos

While reporting this story, I talked to many minority small-business owners who assumed that they’d have an easier time getting approved because the amount they were asking for was so negligible. But as time went on and stimulus funds began dwindling, some owners inevitably turned to outside parties for help, leaving them and their businesses exposed to an entirely different threat.

The New Body Project has five employees including Edwards, and she requested $12,500 to cover payroll. As soon as the SBA loans were announced, she called TD bank, where she had her business checking and savings accounts, to ask about next steps. She waited on hold for over an hour to be told that “they don’t know because they have not been guided by the government yet.”

As she waited for help from TD Bank, and panic-researched online, Edwards got an email from Groupon saying that she could apply for the PPP through their partnership with Fundera. Fundera is an online loan broker, similar to Kabbage or Lendio, which connects businesses to lenders for a “finder’s fee” from the bank. Edwards was dubious, but figured it was worth a shot and applied, and got a response that she’d made it to the next step with one of Fundera’s lending partners, Cross River Bank. Edwards had never heard of Cross River Bank, so she was hesitant, but decided to move forward with the application because she still hadn’t heard anything from TD Bank, and knew the loans were first-come, first-serve. Then the PPP money ran out.

While it’s not always a bad idea for business owners of color who are being underserved by their banks to look for funding through legitimate brokers like Fundera, attorney, stimulus analyst and Entrepreneur contributor Mat Sorensen points out that borrowers should be aware that the SBA-approved lenders these brokers will connect you with are still likely to put their established clients first.

Of greater concern is the lack of information and reliable advice available to desperate business owners, particularly immigrant entrepreneurs for whom English is their second language. The Renaissance Economic Development Corporation is a CDFI, and affiliate of Asian Americans for Equality. They’ve been lending to minority business owners in New York City since 1997, and their managing director, Jessie Lee, says she’s seen a surge in predatory practices.

“A lot of our borrowers are getting secondary information from their ethnic media,” she says. “It’s so confusing that a lot of them have turned to brokers and accountants for guidance, and some of these brokers are predatory. I just found out that one of our clients went to a loan broker who said that they do the PPP program, when they don’t, and then took $2,000 from my business owner.”

Her advice for dealing with third parties? ”Always verify — are you an agent of an SBA lender? Do you have an SBA lenders agreement?”

Related: These City Programs Are Giving Minority- and Women-Owned …

The case for giving CDFIs capital

Renaissance is one of roughly 2,500 nonprofit Treasury-certified CDFIs across the country. CDFIs have long played a critical role in dispatching federal and state funds to the businesses in underserved communities that need them most. And in past crises like 9/11 and Hurricane Sandy, CDFIs dispersed substantial public relief funds (they gave out $12 million in emergency funds after 9/11, and $6 million after Sandy). But as the COVID-19 crisis has played out, Lee says that Renaissance has had to rely on private funds, like part of a recent $1 million commitment from Chase to minority-owned NYC businesses. It hasn’t been nearly enough. When we spoke a week ago, Lee told me that, “Over a thousand businesses have submitted interest forms, and we’re only going to be able to help maybe 200 of them.”

Bishop, the Commissioner of NYC’s Small Business Services, says giving CDFIs nationwide the capital they need to lend in their communities would be a game-changer for minority-owned small businesses. “CDFIs and small community banks are really the only lenders operating in communities of color,” he says, “They look beyond the credit score. They’re very flexible.” Until this point, however, most CDFIs haven’t been able to offer PPP loans. “We’ve been advocating for them to be allowed to participate, but it’s really about liquidity,” Bishop explains.

It’s a catch-22: Because CDFI borrowers are often small businesses in communities of color, many operate with very narrow margins and are now struggling to pay their rent, much less their business loans. Consequently the CDFIs are too low on cash to offer PPP.

Now, thankfully, the Senate’s latest stimulus bill — which should move through the House quickly — has allocated $30 billion of the new $320 billion PPP funds specifically to community banks and credit unions, and another $30 billion to even smaller lenders like CDFIs (a total of $60 billion intended to reach minority and women-owned businesses).

Lee is cautiously optimistic. “We believe this legislation is a step in the right direction because it gives smaller businesses a fighting chance at securing funding and enables CDFIs to help minority-owned business owners in our communities,” she says. “That being said, $30 billion will go quickly and will not come close to meeting the needs of millions of distressed businesses. In the weeks ahead, we will need more financial resources to stabilize our neighborhood mom-and-pop businesses.”

One thing Lee is sure of is that, “The 8 week time period for PPP is unrealistic in New York. We believe businesses will need more funding over a longer period of time, given the city and state timelines for reopening the economy. And payroll assistance helps but businesses still must figure out how to pay their rent. This is a big issue they’re having to confront even after securing a PPP loan. Businesses need flexible capital to address their unique needs.”

Still, while the money is there, any minority small business that hasn’t yet put through an SBA application with another lender should reach out to their community bank, or find a CDFI near them (you shouldn’t apply for the SBA loans with more than one lender).

Heyward, the Durham-based CPA, thinks that moving forward, CDFIs and community banks should play a bigger role. But he thinks this should happen in tandem with the SBA creating more permanent classifications of small businesses, so that truly small businesses with no capital aren’t competing for loans with companies 20 times their size.

“You can call them microbusinesses, or main street businesses, but people with gross revenues under 2 million or something like that,” he says. “Because when anyone in Washington gets on TV and says, ‘We’re doing something for the small businesses,’ I’m looking at the qualifications for a small business and thinking, ‘So what am I, a blip?’ And maybe that could be the domain of the community banks and CDFIs, because the commercial banks could care less about those loans anyway.”

“The systemic prejudice in this situation, in the beginning it’s not racial,” Heyward continues. “But we all know it’s not right. I don’t have to go beat the drum on that.” To the big banks, he says, “I’m just saying that you have to be honest. You have a lot of business owners who are truly expecting to get this money. Their margins were so small to begin with. For minority-owned businesses, this is crushing.”

Edwards is still waiting to see if her PPP application gets approved at Cross River Bank. But in the meantime, after working through the initial shock, she’s been characteristically resilient. In a matter of days, she designed an entire online fitness program for The New Body Project, complete with a weekly family karaoke session. “I won’t throw in the towel,” she says. “I believe this will make us better when we come out of it. It’s never easy to get help when you need it, so I’m blessed my business is something that can be continued online. It’s actually given me the opportunity to tweak my business model. I’m really proud of what I created.”

Related: How to Submit Your SBA PPP Loan Application and Calculate the …

https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/349583