September 3, 2020

John Boardley

In the early 1500s the brilliant Albrecht Dürer had an epiphany. He describes it in a letter to a client dated 29 August 1509. In it he writes that, rather than producing countless unique pieces, he could make a great deal more money by producing prints of his work, and that his only regret was not having thought of it sooner. Dürer was among the first to fully exploit ‘art publishing’ or printmaking, selling his own prints individually and in sets. Today, we’ll take a brief look at a very popular set of prints created at the end of the sixteenth century, by which time European printmaking was a burgeoning international industry.

‘Moderation Disarming Vanity’ by Stradanus. Before turning to engraving later in life, Stradanus was a painter. Photo: Musée du Louvre

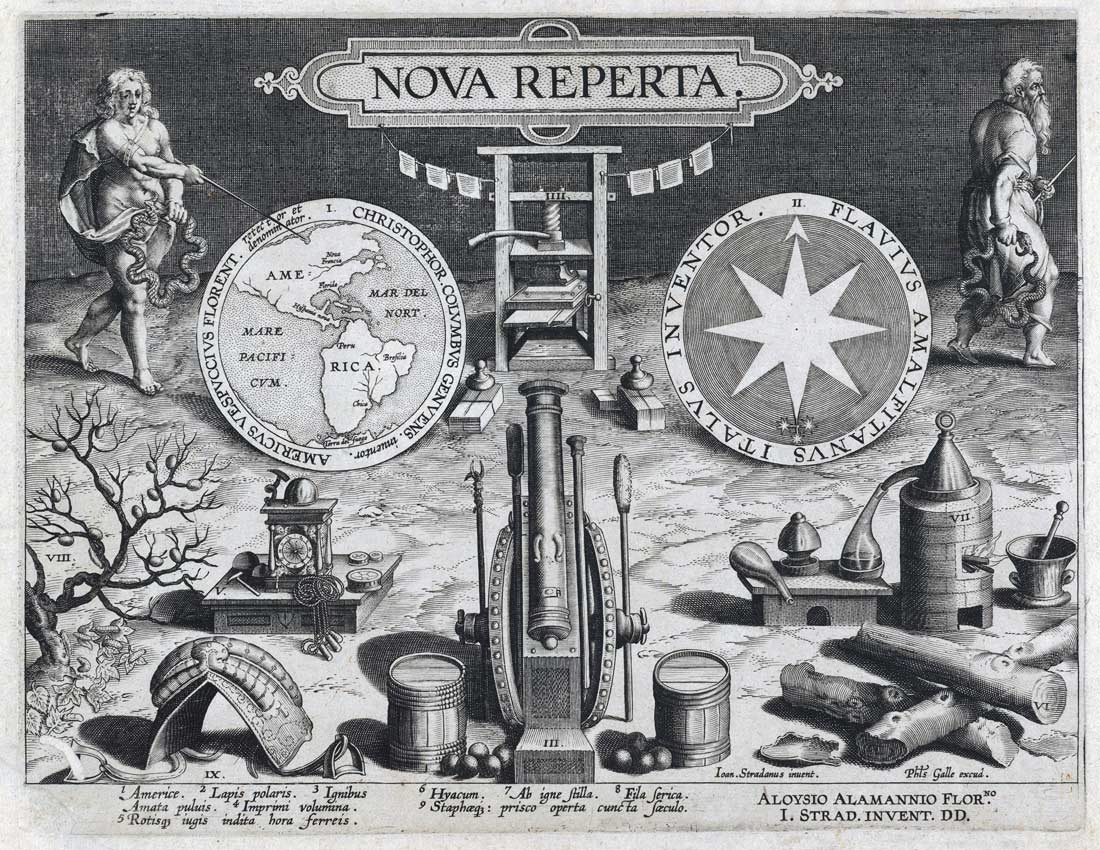

Nova Reperta, or ‘New Discoveries’ was a set of 20 engravings (including a title-page), each illustrating ‘modern’ inventions and discoveries. The print series was a brilliant collaboration between the Netherlandish artist Jan van der Straet, better-known by his Latinized name Johannes Stradanus; the engraver Philips Collaert; the Galle family of engravers and print publishers; and the Florentine scholar Luigi Alamanni (1558–1603) one of the set’s dedicatees.

Stradanus

Born in Bruges in 1523, Stradanus ended up in Florence via Lyon and Venice. He was a versatile and accomplished artist. In the early 1550s, he began working at the Medici court designing tapestries, then worked under Giorogio Vasari. However, like Albrecht Dürer, Stradanus appears to have experienced a similar epiphany, and from the 1570s began putting his artistic energies into designs for print.

From the title-page it appears that Nova Reperta was originally conceived as a title-page plus a series of nine engravings, with a heavy emphasis on America. For whatever reason, the series grew to 20 plates.

* See Lia Markey’s ‘Stradano’s Allegorical Invention of the Americas in Late 16th-Century Florence’, pp. 385–442

The Prime Directive

In 1499, seven years after Columbus landed in the Bahamas, Amerigo Vespucci, after whom the continents were named, sailed to the northern shores of South America. The first plate of the Nova Reperta series portrays Vespucci’s first encounter with America.*

Zoom in: ‘America’ (pl. 1) of Nova Reperta. The caption reads, ‘Americen Americus retexit…’ or, ‘Americus (Vespucci) rediscovers America’. Theodoor Galle’s engraving is remarkably faithful to Stradanus’s original drawing

Holding a mariner’s astrolabe, and wearing a sword and armor, visible under his parted robe, he is both explorer and conqueror, his god-given authority to vanquish represented in his banner and cross. The almost nude figure of an Indianized indigenous woman seated on a hammock personifies America. She is of course portrayed sexualized and vulnerable. According to Vespucci, in what today sounds like the words of a rape apologist, the native women were ‘very desirous to copulate with us Christians’.

“Stradano’s engravings could declare that the New World was a Florentine invention and patriotically revel in these discoveries.” —Lia Markey, p. 119

#See Surekha Davies, Renaissance Ethnography & the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps & Monsters (esp. ch. 8, ‘Spit-roasts, barbecues & the invention of the Brazilian cannibal’), 2016

‡ A recent biographer likens Vespucci to a salesman and sorcerer; see ch. 5 of Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America,.

From Cannibals to Cannonballs

And what scene of colonial conquest is complete without a little cannibalism in the background. This trope was pretty much an invention of the Renaissance.# Contriving a cannibalistic indigenous population meant that it was easier to justify their murder and enslavement. What’s more, Vespucci’s accounts of cannibalism in the New World appear to be, for the most part, borrowed or fabricated, concocted and sensationalized primarily to sale books in Europe.‡ And this ‘oscillation between ethnography and fantasy’,* was by no means accidental, but was always intended to highlight the deficiencies of the conquered and the superiority of the conqueror, ultimately emphasizing the stark dichotomy between savagery and civilization, a construct that the West appears not to have entirely repudiated.

§ If I were an Antwerp publisher in the latter half of the 16th century, I might not be in a hurry to publish a print lauding a Spanish protagonist, what with the Eighty Years War and the atrocities committed during the Sack of Antwerp in 1576

Nobody Invents Better Than Me

That Vespucci appears instead of Columbus is again no accident. Columbus was Spanish§ — much better to highlight Italy’s role in the discovery of the New World, and not any Italian, but a Florentine no less! And if artful propaganda was not enough, then how about unequivocal appropriation: Gunpowder (pl. 3) was of course not a recent European invention, but a ninth-century Chinese innovation. Similarly, the compass (pl. 2) and silk production (pl. 8) originated not in the West but in China.

More Renaissance Invention

International collaborations were a customary feature of sixteenth-century printmaking. The Nova Reperta series was designed in Florence by a Flemish artist and printed and published in Antwerp. Such alliances effected a rich cultural exchange, a cross-pollination of art and ideas which spawned new art and new ideas. The splendid visual culture of the period, rich in its use of emblems and diverse iconography, and even propaganda, reveals much about the artistic and intellectual climate of the age, a time-machine of sorts that permits us fascinating insights into life in Renaissance and early modern Europe. ◉

Shortly after beginning to prepare this article, the Newberry opened an exhibition on Stradanus and the Nova Reperta, co-curated by Dr. Suzanne Karr Schmid & Dr. Lia Markey. Be sure to check out the dedicated web portal, this video, and the accompanying book.