Security awareness training isn’t working to the level it needs to. It doesn’t protect all industries and all people all the time. Social engineering, however, is getting better. The obvious questions are, why doesn’t awareness training work, and how can we improve it?

First, we should separate awareness training from its primary focus: phishing. Phishing itself is not the complete problem — the problem is the social engineering element of phishing that makes it successful. It is social engineering that is the real threat, and purely focusing on phishing means we are tackling just a subset of the problem.

Statistics on the overall effects are difficult to find. Most published figures on phishing, for example, quantify the number of attacks and do not distinguish between phishing attempts and phishing successes. However, an idea of the full effect of social engineering can be seen in the latest IC3 report.

The 2022 Internet Crime Report notes ‘21,832 BEC complaints with adjusted losses over $2.7 billion’ (BEC is pure social engineering). Other figures involving social engineering include, “Investment fraud complaints increased from $1.45 billion in 2021 to $3.31 billion in 2022, which is a 127%;” and “Tech/Customer Support and Government Impersonation, are responsible for over $1 billion in losses to victims.” Romance scams and advance fee frauds also rely on social engineering.

The real question that needs to be asked is, why is social engineering so successful, and how can we tackle this problem? In the following discussion, phishing may appear to be the primary topic because it is most people’s focus; but remember throughout, it is social engineering that underpins it.

Industry opinions on the effectiveness of existing awareness training vary. “Awareness training can be effective in educating individuals about the risks of social engineering, but it cannot completely eliminate the threat,” comments Zac Warren, EMEA chief security advisor at Tanium.

“The effectiveness of awareness training is often undermined by the fact it is difficult to cover all the possible social engineering scenarios, and people can still fall for attacks they have not encountered before,” adds Craig Jones, VP of security operations at Ontinue.

Mika Aalto, co-founder and CEO at Hoxhunt, points out, “Today, with BEC attacks on the rise, it’s crucial that executive leadership is trained on human-targeted phishing campaigns because they are under relentless attack and just one wrong move from them could have disastrous consequences.” This should include leaders in the finance department, and R&D.

“Security awareness training does work,” says Thomas Kinsella, co-founder and chief customer officer at Tines. “Does it stop 100% of breaches? Obviously not. But the larger problem is that organizations push the sole responsibility for preventing a breach onto employees by mandating training and punishing anyone who fails.”

This, he contends, is an additional but associated problem. “Security awareness programs can sometimes have the opposite of the desired effect when they blame or make an example of an employee who makes a mistake. This discourages employees from owning up to their mistakes or even reporting incidents when there is still time to stop an attack.”

While most of industry thinking is that awareness training sort of works, to a degree, John Bambenek, principal threat hunter at Netenrich, is scathing of the whole approach. “Fundamentally, security awareness training doesn’t solve the problem of cybersecurity because it really is a tool of lawyers. ‘See, we have awareness training; so, it’s not our fault.’ If it protects against liability, it’s ‘successful’ in the minds of those who implement it.”

The real problem, he suggests, is like one of the major threads of the National Cybersecurity Strategy – responsibility is placed too much on the end user rather than the cybersecurity industry itself.

“Security awareness,” he continues, “is the digital equivalent of giving someone with a gunshot wound a Tylenol. It may make you feel marginally better, but it doesn’t deal with the real problem.”

We possibly concentrate too much on the ‘what’ rather than the ‘why’: what succeeds for the attacker rather than why it succeeds. The ‘what’ could be a phishing email. The ‘why’ would be ‘social engineering’. The question, ‘Why does awareness training fail?’ could be rephrased as ‘Why does social engineering succeed?’

Bec McKeown, founder and principal psychologist at Mind Science, offers the underlying cause. “The brain is a limited capacity information processor,” she explains. “It can only deal with a certain number of things at any one time. So, it filters information out and makes us take shortcuts to handle the sheer volume of information facing us.”

Our focus is on whatever is currently top of mind. This is usually completing our work as efficiently as possible. Filtering is usually subconscious to allow us to retain focus. It revolves around our own subconscious biases including prejudices, preferences, ambitions, hopes and fears, etcetera. Social engineers understand this.

“They often launch attacks when our limited processors have additional concerns, like the weekend, a holiday, or the outbreak of a pandemic,” continues McKeown. “At this point, our limited processors are already overwhelmed with information, and our biases are heightened.”

The attacker uses extreme biases, such as greed, fear, and the need for haste, as social engineering triggers. Victims are more concerned with finishing work and leaving for the weekend parties than in analyzing the latest email. The victim is in response rather than analytical mode. Subconsciously, it is not a user’s job to worry about cybersecurity – that’s the job of the cybersecurity team.

“When working in a controlled contained working environment,” says Ian Glover, MD of Inspired2 and former president of CREST, “there is an assumption that the institution will look after me. The institution will stop people coming into the building to steal from me, they will protect my personal assets that I take to work, they will be on hand to help me if I have a problem and they will provide technology that will help to stop attacks.” This all limits the amount of awareness of cybersecurity threats, which become readily excludable from our ‘limited capacity information processor’ brains.

It is this combination of information overload, personal bias, and the subconscious diminution of cybersecurity as ‘not my problem’ that allows the social engineer to use timing and triggers to breach human defenses.

There are basically two types of social engineering: spray and pray (which is purely a numbers game), and spear-targeting (which is a skill). Awareness training is often considered to be successful if it can reduce user susceptibility from 30% to 5%. But even with this success, if a spray and pray attacker sends out 1,000 email attacks, 50 will be successful.

Spear-targeting involves researching the target to understand specific biases. This can easily be done via social media and the target’s online footprint. The result is an attacker who knows exactly which bias trigger to pull to ensnare the target with a high degree of success. Spear-targeting by a well-resourced attacker with time and skill will almost always eventually succeed.

Remote working

Remote working adds an additional edge to the social engineering issue, although not everyone believes it is detrimental. Warren believes it increases risk: “Remote work has added to the problem of social engineering because it has created new vulnerabilities and challenges for organizations. With remote work, employees may be more likely to use personal devices or work outside of secure networks, which can increase the risk of social engineering attacks,” he says.

Glover is not so sure. He believes the reverse effect of assuming protection by the ‘institution’ will apply. “As soon as these assumptions of protection and help are taken away, there is a feeling of greater personal responsibility,” he suggests.

Bruce Snell, director of technical and product marketing at Qwiet AI, adds, “Remote work has increased the amount of daily communication within organizations, making it much easier to quickly check the validity of a request that in the past might have gone unchecked.”

But Andy Patel, researcher at WithSecure, points out this increased communication also increases the risk. “Remote workers typically rely heavily on digital communication methods like email, chat, and video calls,” he says, “which can make it easier for social engineers to impersonate contacts and deliver malicious content.”

He also raises the separate problem: “Remote employees who have limited access to IT support or security resources may be less likely to identify, report, or mitigate social engineering attempts.” This can be aggravated where companies are forced to compromise on security policies. “Offering a balance between security and useability may lead to situations where users are able to install bad stuff on their company laptops.”

Chris Crummey, director of executive and board cyber services at Sygnia, continues this theme: “Employees sometimes need to find less secure ways to get their job done. Example, the employee using an unauthorized file share to send a report to a client.”

There is an additional problem. Remote workers are often not good at separating life and work – and spend too much time working. This can lead to a tired ‘limited capacity information processor’ which could become even more susceptible to social engineering.

So far, we have discussed reasons behind the success of social engineering. The danger is that this will get much worse very quickly – because of artificial intelligence (AI). AI will be used to increase the quality and quantity of social engineering attacks. It may also assist technology in detecting attacks, but it will not alter the user’s susceptibility to social engineering.

For the last few years our concern has focused on deepfake technology. “As deepfake voice and video becomes more accessible, more affordable, and more convincing,” comments Al Berg, CISO at Tassat, “attackers will use it to their advantage. We are already seeing use of deepfake voice tech being used in ‘virtual kidnapping scams’ and I would be surprised if it has not already been used to trigger fraudulent payments and fund transfers.”

But, says Patel, “Deepfakes are still rather expensive to create. Thus, their use, even in targeted attacks, will likely remain minimal. Synthetic images and videos are starting to become more sophisticated and easier to create. These techniques may eventually see use, but only in sophisticated, highly targeted attacks.”

The immediate threat comes from the growing availability of large language models typified by the generative pre-trained transformer – the GPT element of ChatGPT that was launched in November 2022.

“WithSecure recently published research on using large language models to create social engineering content. Such models are very capable of doing so, and the techniques we illustrated could potentially be used for things like spearphishing,” he continued. “Another interesting possibility is that language models may be used to power chatbots or to automate the formation of connections with potential victims over longer email conversations, prior to the adversary stepping in.”

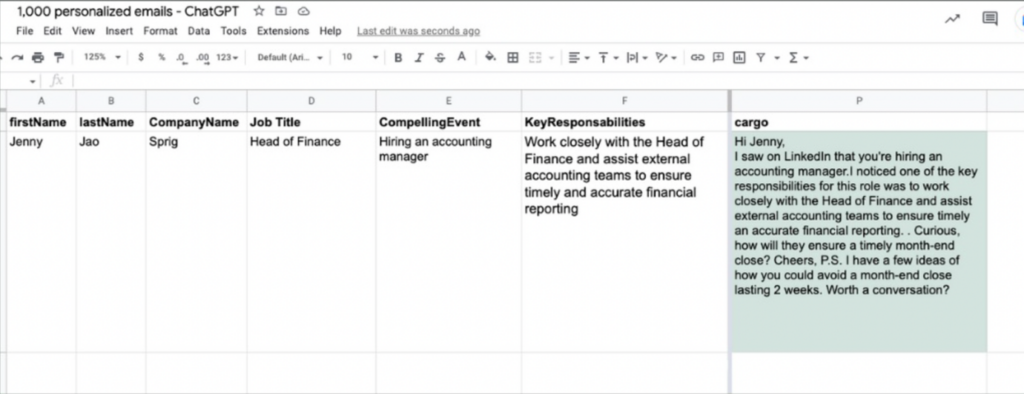

A vision of the future can be found in the publication of How to use ChatGPT (in Sales) by Alfie Marsh, a go-to-market specialist and founder of Rocket GTM. This demonstrates AI-assisted scaling for personalized messages. It uses a free Google Sheets extension called Cargo (described as ‘The openAI addon for sales and marketers’) that interfaces with ChatGPT.

Variables are entered into Sheets (in this example by researching job opportunities on LinkedIn). Cargo is used for the finished email (a job application).

“Instead of writing one prompt per email,” says Marsh, “you can write one prompt template that will spit out thousands of uniquely personalized emails in seconds thanks to custom variables.”

Consider this process in the hands of a social engineer with time and resources to research targets and their triggers. It could evolve into a methodology for effective spray and pray spear-targeting, while allowing reuse by simply changing Cargo’s output email. And this is still the dawn of AI in social engineering.

If the current approach to combating social engineering isn’t working, while the threat is increasing, we need to try something different. Einstein’s definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

The primary problem is that we are training people to recognize attacks, such as phishing, without tackling their personal biases (that is, their personal behavior). Trainees may have the knowledge to recognize phishing, but their biases in the form of subconscious behavior patterns still prevent from doing the right thing.

Security awareness should go together with behavioral training. “Have a layered approach to training,” says Crummey. “Do not stop at awareness – the level you want to get to is ‘behavior change’.”

Behavior change is far more difficult than simple recognition. “What people don’t realize is,” says McKeown, “is that psychologically there is no direct link between awareness and behavior change. Most people believe that if you make people aware, they will do something about it. That is not true.”

People simply react more to their subconscious biases than to their conscious knowledge. Creating a ‘good’ new bias rather than trying to defeat long-standing ‘negative’ biases may be the way forward. It’s almost like the common view of muscle memory – an automatic good response, or habit, that requires no conscious thought.

Achieving this has led to the concept of nudging. “It’s about phrasing cybersecurity training in a way that tries to capture the users’ attention more effectively,” says McKeown.

David Metcalfe, a PA behavioral science expert, has written on the subject. “The answer lies in behavioral science. By introducing ingenious ‘cyber nudges’, companies are able to overcome employees’ bad habits. These nudges are design features engineered into digital environments to indirectly encourage good cyber habits at all levels of the organization. They leverage behavioral insights to drive compliance without affecting functional activities or productivity.”

He provides a simple example related to phishing. “By embedding a small ‘hassle’ in the user experience, like using a pop-up to make people consider whether a link or attachment is from a trusted source, people stop and think instead of acting on their first instinct. As a result, they become better at identifying malicious emails.” This is a simple example that wouldn’t work on its own – in-bred habits would soon lead users to ignore the pop-up. But it is indicative of the approach of nudging users toward better behavioral habits.

Cybersecurity must become second nature to all employees, whether at work or at home. For now, users are primarily taught to reject emails by recognizing typos, grammatical errors, and unknown origins. This is the ‘what’ of a phishing email. But users need to understand more fully the ‘why’ and ‘how’, and the effect of a social engineering attack. Avoiding social engineering must be part of the job rather than an annoying addition to the job.

Right now, a social engineering attack is a buffer overflow delivered by a denial of service attack against the psyche’s limited capacity information processor. We have defenses for similar attacks against our technology systems – now we must learn to defend and positively activate our human resources to the same effect. The concept goes far beyond phishing awareness. It can be used wherever there is a potential threat to the cybersecurity of the enterprise.

Related: 2,000 People Arrested Worldwide for Social Engineering Schemes

Related: New ‘Greatness’ Phishing-as-a-Service Targets Microsoft 365 Accounts

Related: Harris to Meet With CEOs About Artificial Intelligence Risks

Related: Cyber Insights 2023 | Artificial Intelligence

https://www.securityweek.com/security-awareness-training-isnt-working-how-can-we-improve-it/