SHARPNESS: A BOURGEOIS ADDICTION

Tack sharp. Insanely sharp. Razor sharp. Our relentless pursuit of sharpness is like giving birth to a porcupine, backwards.

Looking at gear ads and the photo advice around us, we’re so tortured by exaggerations of sharpness that we can’t tell the truths about it. For decades, famous photos have had naturally soft or blurry regions in them, and careful technique, not gear alone, is a vital part of making sharp images.

In 1998 at age 90, the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, who swore by his Leica, said to Helmut Newton: “sharpness is a bourgeois concept.” Bourgeois means wealth without taste. Image that I am unpacking a brand new $4000 lens for my DSLR. While I may think my gear gives me status and street cred among photo friends, I may have commodity fetishism, lacking the skills to make an expressive image with the pricey optic. Thus, I am bourgeois, in the sense of affluence without taste. Saying that sharpness is a bourgeois concept, Bresson meant we should not let our gear preoccupation interfere with our craft. Even when a sharpness obsession dominates photography, not every image needs to be insanely sharp. Perhaps, for similar reasons, human biology gave us eyes with 5% cones in our fovea for sharp color vision, and 95% rods in our peripheral B/W low-light vision.

Our addiction is hard to break, for our mental bias focuses our attention on the simple questions that we think gear ownership alone can solve. We like to answer simple questions, not complex ones. The complex question is: “How many factors influence the clarity of a photograph and how can we control them?” That’s a difficult question, and we prefer to answer a simpler question: “If I buy this expensive lens, will I get sharper images?”

SOFTNESS IN PORTRAITS

Let’s look to portraiture for examples. Within the context of enthusiast photography, let’s look at how softness can work to express the intent of a photograph. We don’t want backgrounds behind family portraits to be sharp. We can use the magic hour light to for softer, warmer portrait lighting. See what you think.

For this picture of a young woman in Kyoto, the subject is straightforward, the technique is soft focus, and the intent was to express a feeling of this woman’s composure as she sold incense at a Fall festival.

For this image of a musician made with medium format film, the goal was to show this man’s energy and sense of humor as he performed on stage.

Let’s pause here for a musical analogy to portrait photography. Listening to live music, we can hear note bends and those measures where the players are slightly off perfect pitch. This audible asymmetry lets us know we’re hearing live music. If what we hear is too steady, or too accurate, we know it is MIDI, or computer-generated, because it’s lost its human touches. Likewise, seeing a portrait that’s too sharp, it will look not like art but will be artificial, because it’s lost that authenticity, the illusion of how we perceive people should look.

LENS SHARPNESS

These days some folks change lenses to search for sharpness. Yet the majority of sharpness comes from what we do with our gear, not the lens. Changing lenses doesn’t guarantee results; an experienced portrait photographer can make consistently high quality images with an inexpensive gear set using proper technique, and I have made many soft, out-of-focus portraits with expensive gear, because I lacked skill to stabilize my body, camera and lens before capture. For good portraits, consistent technique is more important than a sharp lens. Experience is more important still when we apply it to our subject matter. We do not get guaranteed higher quality images with a higher priced lens.

Granted, sharpness in a portrait lens accompanies the build quality and light gathering speed of the optic. These factors are key aspects useful to wedding pros. Wedding clients want to look great and have their pictures in focus. Sharpness rarely comes up because wedding imagery is not about “sharp.” Qualities of expression, moment and lighting (that pros spend years learning) are what clients value, I believe. However, here, our context is softness in the realm of enthusiast portraiture, not wedding or studio pro imagery.

Do I have a client paying me and do I use a $2000 lens day in and day out? These are intriguing questions we might ask before sacrificing to buy a pro lens with a high sharpness number like a 38 or 40 rating in an online lens review. Unless I am printing an enlargement upwards of 24 by 36, most beginner lenses are just fine. For images shared online, pro lenses seem unnecessary for a screen displayed image the size of a tablet or phone, because we must evaluate sharpness with the screen set to 100%. The only reasons to spend upwards of $1000 on a lens are desire, status, or a pro career in photography. Other than price and sharpness, an 9 item list of lens qualities that give us true long-term satisfaction include: haptics, stabilization, weather resistance, durability vs break-ability, ease of focus for video, brightness transmission, close focusing distance, bokeh and character.

SOFT FOCUS DIFFERS FROM OUT OF FOCUS

There are significant differences between pleasing “soft focus” and “out of focus” portraits. Eyes should be in focus. In the image above, the eyes of both people should be sharply focused, and we can tell that my focusing was incorrect. This is not soft focus or bokeh. It is just bad technique. Now, compare the swimmers to the second image below, a young girl. Although I have softened the surround, the center of interest is in focus enough, although not tack sharp, and the emotion still comes through expressively.

SOFTNESS AND DEPTH

When there are no beautiful human models around, we can call in the dogs! Below, a warm-hued, fog-shrouded morning light softened the background and added depth to this boating image. If it was tack sharp, the harbor background would have been distracting, taking away from a portrait of my drowsy friend. Let’s see one more example with the dog before we turn our attention to bokeh.

I scouted a location ahead of time for the photo, taken at aperture of f/5.6. In post processing, the background was softened and color was altered. The trees and home in the background add a sense of place, but are left soft so the focus is on humanity in the moment.

I scouted a location ahead of time for the photo, taken at aperture of f/5.6. In post processing, the background was softened and color was altered. The trees and home in the background add a sense of place, but are left soft so the focus is on humanity in the moment.

PORTRAIT BOKEH

Coined by Mike Johnston, bokeh means soft, fuzzy, blur. Often misunderstood to mean mainly a lens aspect, or an app, or a photograph entirely out of focus, classically authentic bokeh is not related to those things. Bokeh is the feel or quality of the out of focus area. It is not gear, apps or selfies. In a portrait, we may want the person in clear focus, to direct the viewer to their beauty. We may also want part of the portrait in softer focus. When bokeh dominates a portrait, we have the windshield without the car, appearance without being, and blur but no compelling subject matter.

While bokeh is related to the blades of the lens, good bokeh is more about composition. It can support the sharper areas of the photograph when it adds negative or opposing space to the spatial composition. Well composed subject matter, not bokeh matter, is what makes portraits meaningful and lasting. In portraiture, bokeh is effective when combined with story, symbol, time and expression. Character in photographer refers to qualities of a lens, and to human qualities of a portrait subject.

Character in photographer refers to qualities of a lens, and to human qualities of a portrait subject.

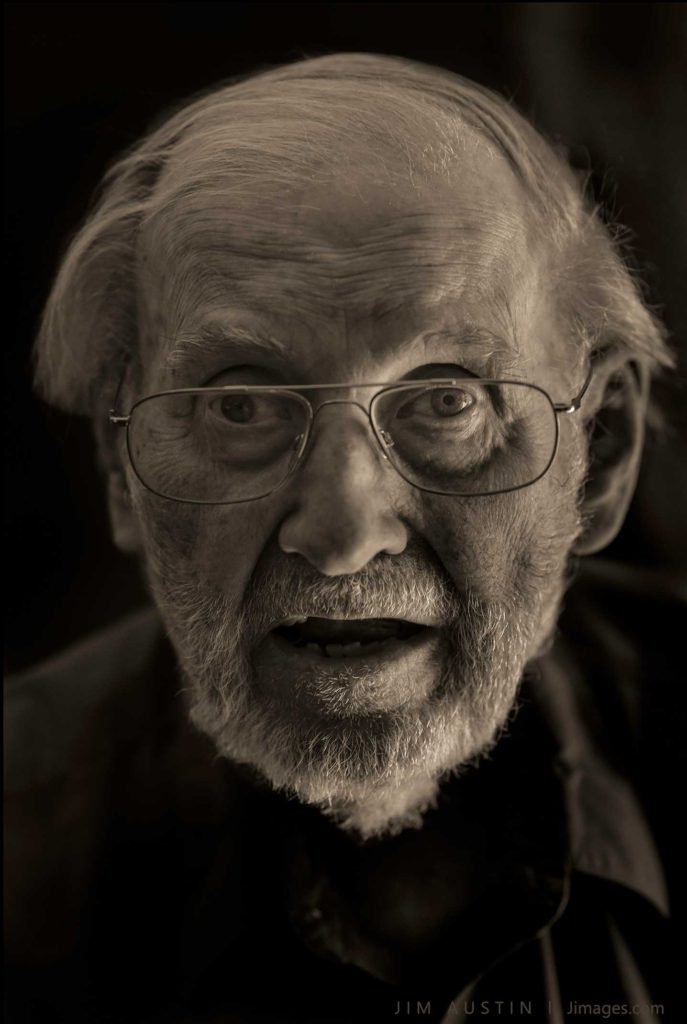

The image above was made with an inexpensive 50 mm 1.8 lens in natural light. Only a small percentage of the image, the man’s eye, is acceptably in focus but not tack sharp. The goal was character, a portrayal of later life, not sharpness. I initially made this portrait to practice with 50 mm portraiture.

I hope we’ve seen that letting go of sharpness has some benefits. For portraiture, let’s spend less of our creative energy on gear, and more on gaining experience using good technique. Then, when we look again at what makes our photographs a bit more dynamic, perhaps we can tread more softly.

https://www.apogeephoto.com/sharp-look-again/