The Oscar-winner also gives advice on how to become an animation director, embracing your inner child and how he balanced being one of three directors on Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Like many working in the creative industries, Peter Ramsey’s career has seen some highs and lows. He’s the first black director to win an animation Oscar, for co-directing one of the best films of this decade – animated or otherwise – Spider-man: Into the Spider-Verse. His previous film, Rise of the Guardians, saw him described in 2012 by one blog as the ‘Obama of animation’, a label that keeps reappearing in the headlines of newspapers, trade titles and London-based creative websites.

As is often the case with Hollywood, such high expectations aren’t always matched in box office takings, when Rise of the Guardians flopped – but the film went on to find its audience on the small screen, where it was massively popular and has a cult fan base of both children and adults (including a friend who messaged me as soon as she heard I was interviewing its director to say “tell him I’m THE BIGGEST FAN EVER”).

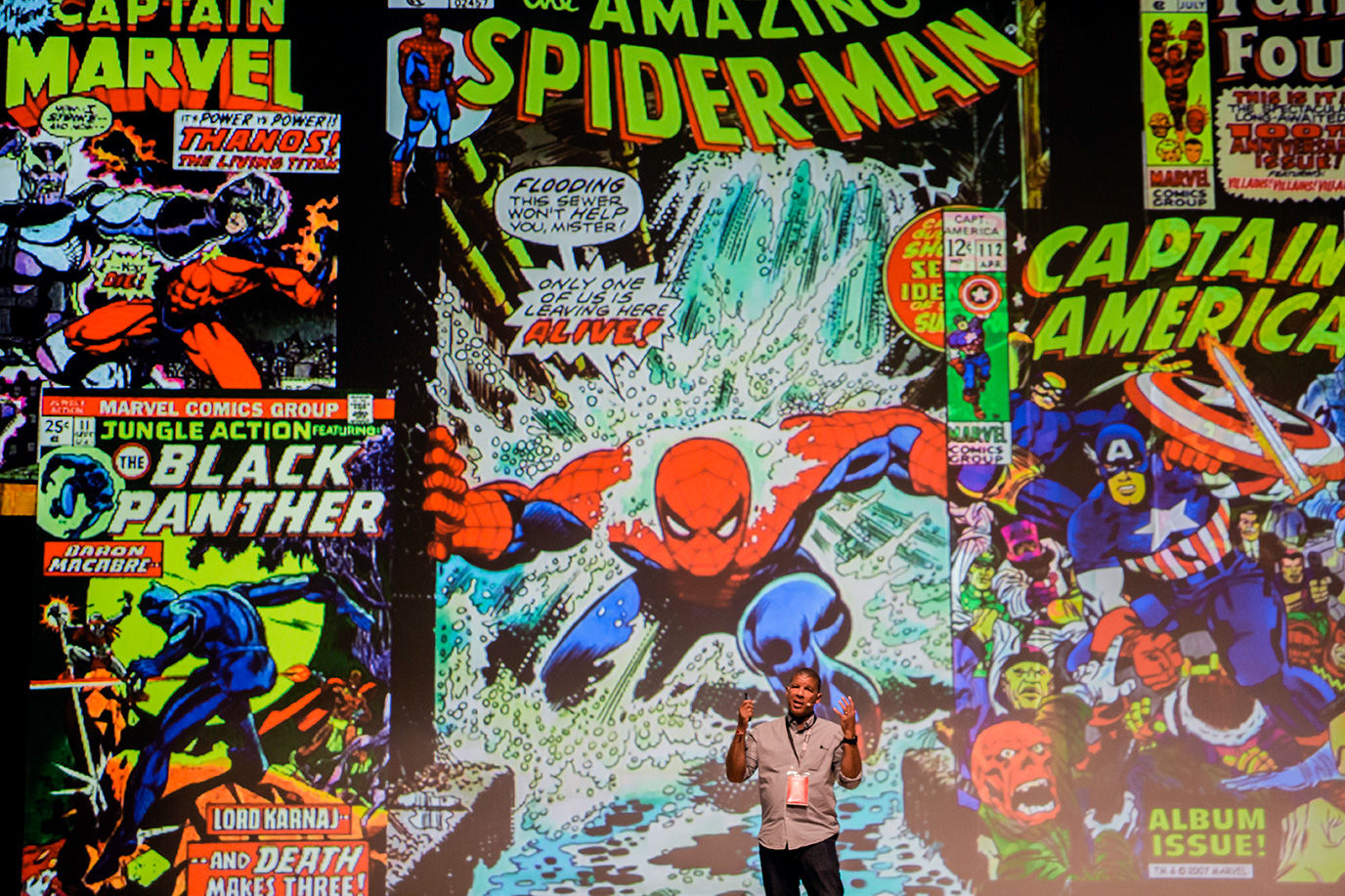

I interviewed Peter shortly after his talk at the THU 2019 conference in Malta, a boutique event with a festival feel that encourages openness and honesty in both speakers and attendees.

In keeping with this, there’s a humility to the way Peter talks about his career, a knowledge that he’s indebted to those who helped him in his career and that he has to pay that forward, that what he’s achieved means that he’s a role model to other animators of colour without feeling that he has to be some idealised, inspirational figure.

“For most of my career, there haven’t been a lot of black people doing what I do,” he notes. “I mention that to say that I never really felt like a pioneer because it was just being able to do what I enjoyed doing. I just see myself as somebody who was in the right place where the lightning bolt struck.

“If that in any way can help anybody else and encourage anybody else, I’m all for it. So I talk to kids and try to do anything that promotes diversity or inclusion. I try to do it as much as I can whenever I can. And I always get a lot out of it myself.”

It’s clear that while during his talk he laughed off Obama comparisons, the mantle – a costume perhaps, in the superhero sense – of being a role model is something he’s happy to wear.

“It’s very important because I know what it would’ve meant for me,” he says, “especially as a kid not having that kind of role model for that kind of thing. When I was a kid I didn’t know that many people who could draw, period. I didn’t know any adult artists – let alone any adult black artists. I felt like it was a weird mutant trait or something.

“So just knowing that there are other people into the same thing, who come from where you do, who are like you, who are into the same thing as you – you can see how important it is to people.”

Peter’s thoughts don’t just come from imagining if there had been prominent African-American animators when he was growing up, but from his own experiences of meeting up-and-coming black creatives at events such as THU and Lightbox. Many of these are young artists and animators, but some have started in the industry later in their lives.

“I met an African-American gentleman [at Lightbox] who had been in the army for 16 years,” says Peter. “He had been discharged and his kids were grown and he had this passion for getting into animation – and it was amazing.

“It’s just a great thing when people from backgrounds like ours can see art as a passion that they could follow, regardless of how old they are. It really moved me to see this guy who was a full-fledged adult. And it struck me as the kind of thing that 20 or 30 years ago, I don’t know if a black man in America would’ve seen that as viable – but this guy did and he really was pursuing it.”

One potential downside to being seen as a black role model is that you might feel that you have to focus on projects that continue to push the representation and diversity of black characters – and characters of colour in general. Peter doesn’t feel pigeonholed by this.

“It doesn’t put pressure on me,” he says. “I don’t feel like I have to do any particular kind of project – and I don’t feel like I’m in any sort of a box.”

In his perfect world, all animators – no matter what their background or identity – would be able to work on any type of project. What matters to him is not just that black creatives get to tell more stories that are tied specifically to their identity, but that a greater diversity of people get to tell a wider range of stories.

“Other people being allowed into the creative conversation to tell different kinds of stories, I think it energises all storytelling,” he says. “It’s not a zero sum game [where there are] less movies about white characters. I want more about everybody.

“I really do think that it’s like you’re opening up a window in an attic and letting some fresh air in. There’s great things that will come with that and the air that’s in there is going to get energised and charged with the new creative spirit – and it just opens up room for more kinds of stories to tell and more ways to tell them.”

Outside the conference hall earlier, I met a young storyboard artist. While chatting, I mentioned I was interviewing Peter, and he asked me to ask Peter a question. So I put it to Peter, does being a storyboard artist make you a better director?

“It’s kind of a philosophical question,” he answers. “Are you a storyboard artist who directs or are you a director that storyboards?

“[Like a good director], a good storyboard artist understands things about economical storytelling,” he notes.

Also both roles require an understanding of the importance of having a viewpoint. They need to know how to construct a sequence so that the viewer knows what characters they’re identifying with at any given moment.

“There are ways you can do that through pure filmmaking technique,” says Peter. “It’s actually one of the big things that I look for in board artists, because a lot of board artists in animation come up through TV and it’s a different mode of storytelling than really good immersive feature storytelling. It tends to be more objective in TV.

“In movies, you really want to be in a character’s head and be empathising with the characters.”

The step between being a storyboard artist and a director can seem a huge leap, but to Peter says that it’s more about doing than being.

“Becoming a director has got such a weird mystique around it that part of the job is getting the job,” he says. “Part of it is deciding you’re a director and getting somebody else to realise or agree with you that you are.”

Directors can seem intimidating to those working for them. Peter says he found this when he was first starting out in his career working as a storyboard artist on live action films, but got over it when he noticed the directors he was working for weren’t perfect.

He remembers that “after a while I started thinking ‘well, that guy doesn’t know all the answers’, and ‘I figured that out for him and he didn’t know how to do it.’ Or ‘the production designer came up with that idea’.

“That’s when you start to understand that it’s not about being infallible and it’s not about knowing everything, but it’s having a relationship to the material and having a vision in your head.”

There are many paths between the two, but there are some core skills that you need to have – or acquire – if you want to succeed as an animation director.

He says that one of the most important traits a director needs is a cool head: the capacity to deal with obstacles that get in your way, whether caused by circumstance or people. Wider people skills are also essential.

“More important than having any kind of business savvy, or real knowledge of the industry per se, is having an ability to read people and to function socially,” he says. “So much of the job is about communicating your ideas and vision, and enlisting people to help you or to work with you.

Being able to work effectively with others when you’re the person in charge – or at least as much as you can be in charge when you’re working with producers and the studio backing a production – is one thing, but for Spider-verse, Peter was one of three directors.

I asked Peter how he, Bob Persichetti and Rodney Rothman managed differences of opinion between the three. Did it sometimes, I asked jokingly, come down to a vote?

“Kind of,” he says. “We did have points of contention about how to solve [problems] and sometimes it could get a little testy. But we honestly had too much work to take too much time to actually be at each other’s throats.

“The original vision that Phil Lord set down and the treatments that he wrote very early on were so clear and so strong. We all knew [that] if we could catch this in a bottle and translate that to the screen, then we will really have something special.”

“So we always had a little North Star to steer toward – and that that was the thing that ultimately kept us from dissolving into chaos.”

2019’s THU had an extensive manifesto based around a journey to find a seventh unicorn, but what this really comes down to is listening to your inner child. As someone who describes his films as “human stories disguised as superhero stories”, this resonates with Peter.

“For me, [listening to your inner child] has to do with an openness to experiencing emotion,” he says, “and being willing to put aside preconceptions and expand your ideas of what concepts, perspectives and ways of looking at the world are viable.”

He notes that children are often capable of coming up with truly novel ideas because they are ignorant about how films, or stories in general, or the world as a whole, are supposed to work.

“I’m never one to argue in favour of infantilising people,” he finishes. “I’d like people to be sophisticated, but I do feel that people getting really trapped in their own perspectives.

“Being able to step out of those sometimes and ask the crazy question – or look at something from a totally different point of view – is a skill that you may have a more direct pipeline to if you’re in touch with your inner child.”

https://www.digitalartsonline.co.uk/features/motion-graphics/spider-verses-peter-ramsey-on-why-he-doesnt-need-be-obama-of-animation-help-inspire-next-generation-of-black-animators-artists/