The art legend tells us which Kanye cover he made in a day, and why he’s becoming a folk singer.

When I first see him, the man dubbed the Warhol of Japan is walking into an entirely different room next to the one where we’re due to chat. With long grey hair and colourful street wear, he’s how you’d expect a grand old wizard of neo-pop art to appear (or disappear, as in this case.)

After some moments waiting by myself, Takashi Murakami enters by surprise from a door behind me, this time with a gnawing kawaii critter on his head for a hat and a massive paw-like claw on his left hand. The man is in persona, and I enter mine of affable arts journalist.

We’re sitting in the silent underbelly of a convention centre in Long Beach, USA as somewhere above us hundreds pour into the two-day ComplexCon, where Takashi clothing and toy merch is being sold among countless other examples of streetwear and designer toys. The con is also a place for music, and the night before saw Pharrell Williams making an appearance, a friend of Takashi’s whose promo videos have been blessed with his magic touch. There was also a performance by Kid Cudi, one half of the Kanye West collaboration Kids See Ghosts, in my view the best thing West’s made since Yeezus and which also came adorned with some of that terrific Takashi art (below, left.)

Talking with Takashi about all things hip hop, I discover the production process for Kids See Ghosts‘s artwork was a much more hurried process than the one for Ye classic Graduation, the cover where the rapper’s old mascot of the Dropout Bear is sent flying through very psychedelic skies.

“This was a really funny story,” Takashi tells me when I bring up my love for the Kids LP. “Kanye asked me for like 18 months, ‘Please make me something.’ But that something, I did not know what. Then, when (Kids See Ghosts) released, he said ‘Uh, Takashi, I need it tomorrow.'”

Takashi laughs at the memory, telling me he was in America at the time but due to return to Japan the next day. “So I had to spend all night communicating with my assistant in Japan (on making the cover), and then he contacted my assistant saying, ‘Please come to Los Angeles for the listening party!’

“But I couldn’t do that, and now I was at the airport, transiting from Chicago to Japan, and Kanye’s assistant, again, again, again saying I had to go to the party. So we paid for a very expensive air ticket to Los Angeles, just for that listening party!”

Los Angeles is where me and Takashi are having our conversation, during which I learn the artist visits the States at least every two weeks (and that, unlike some, he’s a big fan of Kanye’s latest opus, Jesus Is King.)

You have a strong relationship with America and hiphop then, I suggest to him.

“I think so, yeah. Very much. I made my debut in New York City, that’s why. My hip hop experience (meanwhile) came from the Beastie Boys, like (white boy) hip hop. So I wasn’t in touch with the roots of rap, it was just that the Beasties were a big hit in Japan at that time, and I became a big fan.”

Takashi is talking about the 1980s, and for a moment I put on my music journalist hat and ask him how influenced he was by the sounds of Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO), the groundbreaking Japanese trio of Ryuichi Sakamoto, Haroumi Hosono and Yukihiro Takahashi.

He replies talking about Hosono’s pre-YMO project Happy End, a 1970s group which mixed Japanese leanings and American folk-rock as an exploration of Japanese culture under Western influence.

“Happy End made very experimental music, and that was my roots (as opposed to hip hop.) I and they (as Japanese) had to find out what Japanese style exactly was. And YMO came from that, and in their music I found my voice.”

Nodding to rap’s loop-based history, Takashi refers to YMO as a ‘sample’ in his work, taking from them his own exploration of Japan through art.

“We are from the environment of before, and that’s why I’m very understanding of this movement,” as he says.

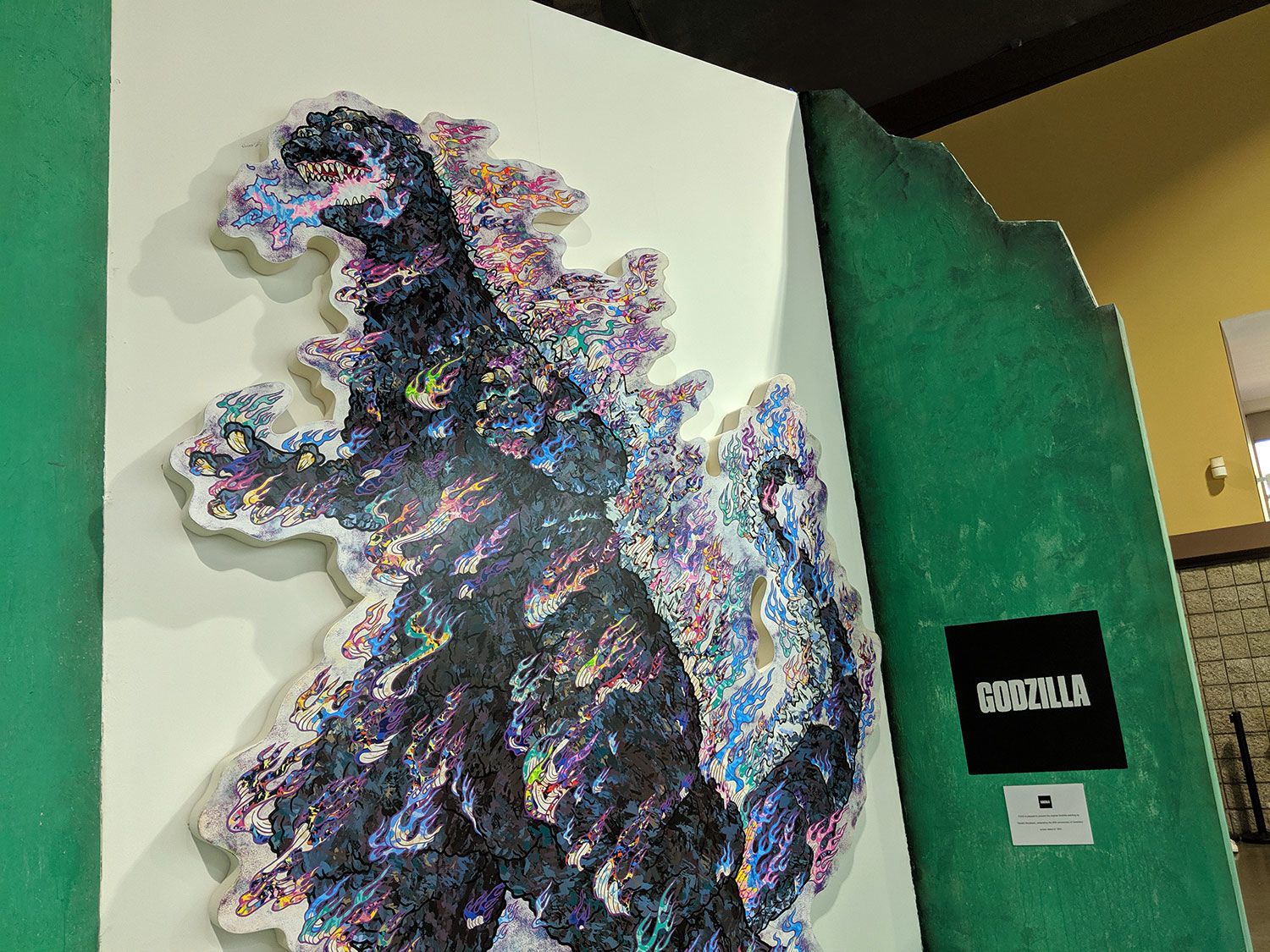

Referring to a new Godzilla piece of his made especially for ComplexCon, Takashi develops this idea of Japan as a country searching for its own identity following the war, comparing the mutation from radiation that is Godzilla to what he sees as the “complete mutation” of Japanese culture.

“We lost a war, and after the economy looked good but (the reality) was still super bad. There was no goal for most of the country.

“So, people’s feelings were completely twisted in Japan,” he continues. “Everything was a mutation.”

Later I find myself staring at his Godzilla tribute, probably the second best illustration of the classic monster this year after Yuko Shimizu’s version for the Criterion Collection box set. I imagine the two renditions duking it out in a duel to the death, each a beautiful creation by two artists born a generation apart but, thanks to finding their voice amidst the roar of the world, of equal relevance.

You should see him in a crown

One could also say Takashi has stayed relevant through his many collaborations over the years. When his career gained momentum in the late 1980s, he’d dissociated himself with the Japanese art scene and what he deemed as its habit of appropriating Western trends. On his own he began the so-called ‘superflat’ movement, representing himself with a 2D manga-like mascot indicative of the style, not of a dropout bear but a mutated Mickey Mouse instead. A figure of one then, hidden behind a solitary character called Mr Dob, no mutant Minnie by its side.

The 21st century though saw Takashi become a monster of collaboration, partnering not just with Pharrell and Kanye but also brands (Billionaires Boys Club), actors (Kirsten Dunst) and ComplexCon itself, at which Takashi serves as artistic director. It also saw him start company Kaikai Kiki, through which he became a manager and mentor for younger artists, with a studio component that sees others bring the artist’s work into the digital realm (by his own admission, Takashi is not a digital artist, analogue remaining his weapon of choice.)

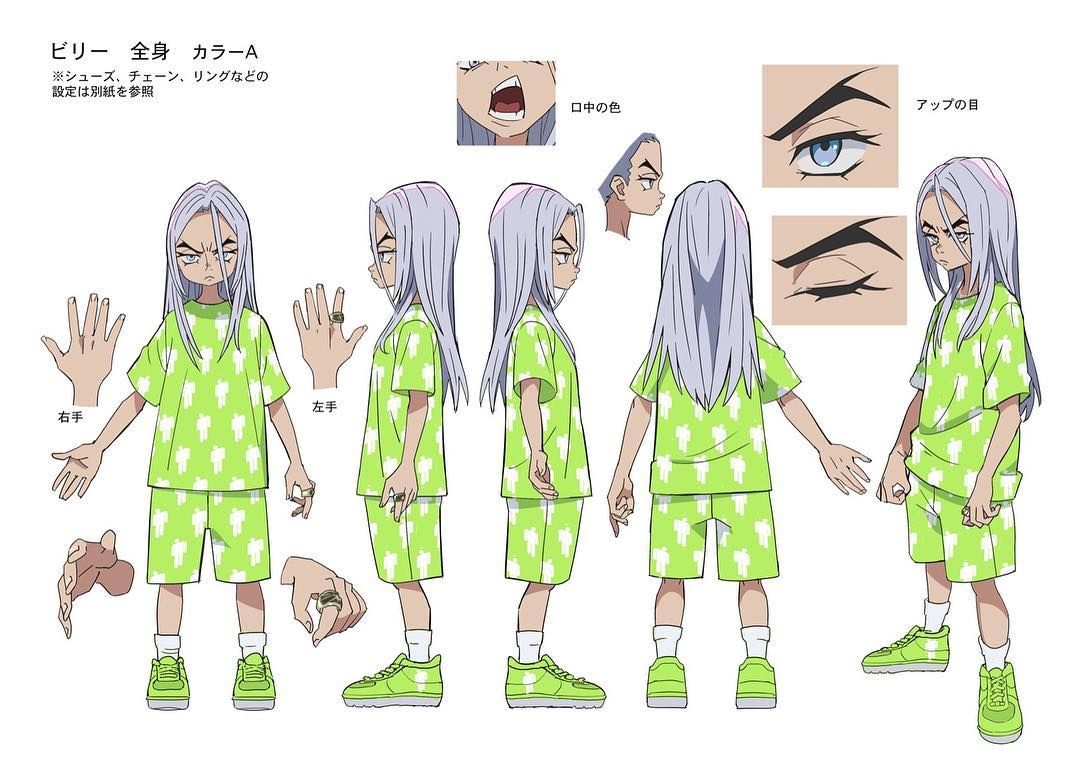

The most notable partnership in recent months has been between him and the very singular musician Billie Eilish, directing a promo for her oddball urban pop of you should see me in a crown and creating a striking cover star shot of Eilish for Garage magazine. With the additional spawning of toy figurines and streetwear, the pairing has been a multi-faceted project, albeit one coming from the most laughably simple of places.

“I didn’t know who she was,” Takashi admits with a smile. “But I saw her online wearing like a ‘fake’ brand and I pushed the Like button and commented, ‘Oh, this is great.’ And then she responds, ‘I’m going to Tokyo, let’s meet.’ So she came to my studio, and the next day we did some motion capture.”

Improvised or not, the team-up has arguably made Takashi shine with a new American generation not only as his videos for virtual idol Hatsune Miku did with Japanese teens this decade, but also as his beloved Kanye projects did back in the 2000s.

Besides keeping him in perpetual relevancy, partnerships also seem to keep Takashi invigorated after a quarter century of being in the business.

“Maybe I am bored,” he admits, pondering for a minute. “That’s why I have to collaborate with somebody, why I have to do many, many things. I manage other artists, I’m making movies. I’m not like most people.”

“I’m an artist, and I’ve survived for 25 years. That’s meant each time I have to find out what the Next Thing is but now. Artists are looking for their own way to survive again, again and again, right? So, for example, if I’d been making just flower pieces, I could settle down the pace and just sell and count the money. But I’m not interested in this, and that’s why I am always looking for something. So this time I’m singing a song.”

A song? I’m not sure if I’ve heard correctly.

Takashi nods. “The most important thing right now in the music industry is the message. People want to get a real message, and they can get it from music. That’s why I’m singing a song.”

As he talks, his interpreter passes me a smartphone, on which I see a rough cut of a promo for Takashi Murakami’s first ever music release. In it, a young man walks around sleepy Tokyo suburbs, wearing a hat much like the one Murakami’s still wearing. Animation will be added later to it I’m told, and while I don’t watch all of the seven minutes that make up its running time, I can confirm the music is resolutely folk, with Takashi’s talk-singing vocals narrating over acoustic guitar. Hip hop this ain’t, Murakami fans (although rap is essentially words spoken quickly over music, lest we forget.)

“This is a nostalgic thing,” Takashi confesses. “The father of my guitar player is a super famous folk singer in Japan, very much like Bob Dylan. When I was a kid I listened to him.”

As I listen to the track, I remember an event put on in London this summer by super famous mangaka Urasawa Naoki, in which the 20th Century Boys creator mainly played folk rock songs on stage alongside the occasional bout of live drawing.

Takashi’s tickled hen I tell him about this show. “Well, we are are completely the same age, completely the same generation!” he laughs.

With all these projects in merch, media and now songwriting, I’m curious what Murakami is most passionate about.

“Making movies,” he answers in a heartbeat, telling me how he first realised he’d become a success whilst at the red carpet premiere for his first movie, Jellyfish Eyes. Takashi is currently trying to fund a sequel to the 2013 movie, an endeavour that has almost left him bankrupt.

“I’m not a businessman you know, because I lose money a lot. I’m very bad at organisation, too; almost every day I have a meeting about the sequel which is so stressful because I have no time.

“I’m just there in the meeting because I’m the one paying for everything. Then they ask me, ‘How do you think?’, and I have to say something. But I’m not Quentin Tarantino, so I just say ‘Oh, looks good.'” Takashi laughs. “I just don’t have confidence, and that is very stressful.”

Before we finish up, I ask Takashi a question passed over by one of his many fans, Ben O’Brien (aka Ben the Illustrator), who attended a panel talk in Tokyo once where Takashi advised that young artists everywhere should ‘follow your bliss.’ Does he still believe in that philosophy Ben asks, or, after all of Takashi’s success, does he perhaps feel there are other ways to build a life in art?

“Bliss?” a confused Takashi repeats.

Happiness, I offer.

“This is crazy. I probably didn’t say that.”

Why not, I wonder.

“I am not a happy man!” he replies, smiling.

I look up and see the thing on his head grinning at me, and realise that I’m looking at two smiles instead of one.

Such is the magic of the wizard, whether a happy one or not.

Note our interview with Takashi was held in English and has been slightly edited for clarity. Photos by RK are ©️2019 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

https://www.digitalartsonline.co.uk/features/illustration/takashi-murakami-reveals-his-secret-25-years-of-success/