I’m a firm believer in the power of a live performance. A television broadcast or DVD doesn’t capture the same thing as a theatrical production or a concert. You gotta be there.

But what about when you can’t? What recourse is there when you’re in love with an artist or performer who you can’t physically interact with for any number of reasons?

I’ve thought about this for decades from a few perspectives: as a former full-time music critic; as a frequent chronicler of how information is presented and exchanged online; and perhaps most of all, as a music fan who had one freaking band slip through his hands.

I will never see my favorite songwriter in concert, right in front of me, reacting to my cheers and enthusiasm. But if any performer was going to vanish just as I teetered into my concert-going years, at least this one had some surprises for me five, 10, even 20 years later, all just a few mouse-clicks away.

“I was little, I didn’t know $#!*”

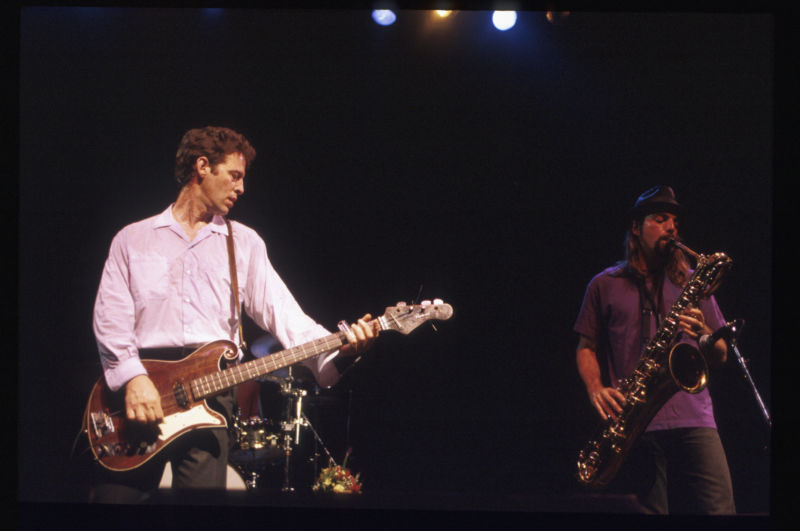

If you’ve heard of the musician in question, Mark Sandman, you likely travel in some select music circles. Sandman was best known as the lead singer and bassist for the Boston-area rock trio Morphine, who rose to mid-level, college-radio fame in the mid-’90s. Theirs was a unique sound: just bass, drums, saxophone, and vocals, swirled together in a style that Sandman dubbed “low rock.” Saxophonist Dana Colley played his baritone sax like a guitar, while Sandman’s unique slide-bass style favored thudding chords and far-from-subtle grooves.

I found out they existed the same way a few thousand people from my generation did: by a quick-hit report on MTV News. The cable channel would occasionally air five-minute vignettes about up-and-coming bands, usually when they’d signed to mid-level record-contract deals. Morphine’s “You Hear It First” snippet wasn’t well preserved; I’ve struggled to find it online over the past 20-plus years, but I can pin it to a specific era and a specific friend who I watched it with. One of those seared-in-the-brain childhood memories.

But at that age, if it wasn’t in a BMG or Columbia House catalog (“10 albums for one penny!”), I pretty much couldn’t buy a CD in question. So my real appreciation of the band was held up a few years, until I started going to the local used CD store to spend whatever part-time job money I hadn’t spent at Software At Cost Plus 10% (an actual store in Dallas for a few years). I flipped through the CD store’s “new arrivals” bin, where the good stuff usually hid before getting alphabetically sorted by staffers. One time, I found a Morphine motherlode. I bought it all.

Were I typing this article at a music-centric site, I might regale you with a lengthy, overwrought description—one of exhilaration at the band’s crunching, unique-sounding riffs, another of my love for Sandman’s straight-to-the-gut lyrics, and a third about how foolish I immediately felt for not looking up their albums sooner. Instead, I’ll just embed a song.

I knew this was outside the normal rock-radio realm of the time, and I also quickly figured out that not every band with a CD at my local store had quite “made it.” That was OK for me. I didn’t fit in at my school. It was cool to have a band to reinforce that feeling—something weird, edgy, catchy, and poetic that didn’t require me to dress like a metalhead or a goth.

But as I hinted earlier, my increasing fandom didn’t go according to plan. My hopes of eventually seeing Morphine in concert fell apart 20 years ago this week. On July 3, 1999, Sandman died at the age of 47, shortly after suffering a heart attack in the middle of a concert in Rome. No foul play or drugs were detected; Sandman had a history of congenital heart failure in his family, and he’d brushed aside troubling symptoms earlier that day. The rest of that 1999 summer tour was, unsurprisingly, canceled. I had just turned 18 and would’ve finally been able to see them at age-restricted venues.

“11 years later, still don’t know any better”

I know a lot about Sandman’s death. I also know a lot about the album that was about to launch when he died, about the other bandmates’ efforts to create a tribute concert series in the wake of the tragedy, about a pair of documentaries about Sandman’s legacy, and more.

I wasn’t nearly as encyclopedic about Morphine at the time. In hindsight, I realize how numb I was to Sandman’s death. Other musicians I really liked in my teens had come and gone: Kurt Cobain, Layne Staley, and Shannon Hoon, just off the top of my head. And my fascination with music was only beginning to blossom; barely two months after Sandman’s death, I had moved to Austin for college, where I became a live-music addict. Between cheap concerts and free file-sharing downloads, I was distracted.

My mourning period for Sandman didn’t really land for some time. I’ve come to realize that’s typical for grief, in terms of life events reminding us of the people and things we miss. But my first blush with this about Sandman came from a surprisingly geeky source: Soulseek, one of the many peer-to-peer file-sharing apps that littered the post-Napster landscape. I favored Soulseek’s simple interface over the bloated likes of Kazaa and Limewire, and I loved its default encouragement to pick through uploaders’ individual libraries. Search for a Weezer song, then pick through a Soulseek uploader’s full collection, and you might find other Weezer rarities, if not other exciting new bands.

In Morphine’s case, Soulseek introduced me to a surprising number of bootleg concert recordings, which I found while trying to fill out my collection of the band’s B-sides. Some of Morphine’s bootlegs came from jam-band fans who’d been to the Horde Festival. (Morphine weren’t a jam band by any stretch but got booked at Horde for some reason.) Others just came from die-hard fans. Most of these sets included clearly recorded introductory speeches from Sandman: “Ladies and gentlemen, we are Morphine, at your service.”

This wasn’t the same as grabbing albums and B-sides. These were documents of a band experience I’d never, ever get to see. I’d finally started going to a ton of concerts (and even bootlegging a few local favorites). For the first time, I felt myself trying, and failing, to fill in the gaps of a missed experience.

Still, I loved the songs, so this material tided me over before the handlers of Sandman’s estate began officially unearthing a mountain of posthumous output—enough to make the Tupac Shakur estate blush. Sandman invested in a home studio early in his career, which he dubbed “Hi-N-Dry Studios,” and there, he put countless experiments and musical ruminations down on tape (not on hard drives). This was still the era of the B-side and single, which meant a few of these weird one-off songs had reached retail before his 1999 passing. (A personal, macabre favorite is above.)

The first major issuance of posthumous material came from a 2004 three-disc box set, simply titled Sandbox, which included a surprising number of entirely new songs. Sandman dabbled in a number of side projects, particularly the trippy, techno-laced Hypnosonics, and I was overjoyed to finally get my hands on more recorded examples of his oeuvre. The sentiment quickly grew bittersweet. Was it easier to miss Sandman with more songs to enjoy? Or was it harder to miss him with the realization of how surprising and diverse his output really was?

In the years since Sandbox‘s launch, even more music has emerged. What’s more, his musical legacy has fallen into a strangely sweet spot on the Internet: big enough to have a huge number of fans uploading all manner of bootlegs and rarities, yet small enough to avoid a DMCA smackdown. I cannot recall any videos from my long-running “SANDMAN/MORPHINE” bookmark folder drying up due to a copyright claim, in spite of his biggest studio albums being available for purchase (let alone some snazzy vinyl re-releases).

“It’s way too late for me to change”

The best stuff all seems to come from one YouTube channel, in operation for a little over two years, with a strange nickname attached: Sito Lupion. As I’m writing this from the perspective of a fan, not an embedded member of the Boston music scene, I don’t have any personal insight about who this person might be. But as a rabid Mark Sandman fan, I can assure you, they have some incredible level of access to Sandman’s personal archives.

Bootlegs. Previously unreleased songs. Rare VHS rips of TV appearances. Alternate studio takes of the band’s biggest hits. Versions of songs that have previously only been released on vinyl (meaning, no digital-download option).

Sito Lupion’s channel includes a few videos of the band’s hits, clearly tailored for newcomers, but most of the channel plays out like a gift to the hundreds of people who, like me, became infatuated with Sandman’s brief-and-shining period of artistic output. Even in the week-long run-up to this week’s sad anniversary, the channel managed to post entirely new songs and recordings.

As a result, I’ve gotten to “attend” dozens of concerts that I otherwise never got to see as a kid. Morphine rarely toured the American South, and when they did, their shows were usually at 18+ or 21+ clubs, which wasn’t much help for my born-in-1981 self. I’ve since attended concerts featuring the band’s remaining members (Twinemen, Vapors of Morphine), and I’m glad for it. Dana Colley in particular is a saxophone player beyond compare (and I say this as a guy who both loves certain jazz eras and detests most rock bands’ experiments with wind instruments).

“I hope I’m sittin’ on the back porch”

But Sandman was the guy, and on the Internet, to me, he still is. I’ve gotten to see so many Morphine shows on YouTube that I have started to pick up on band mannerisms, on slight experiments and alterations of a given song, on the band’s ability to pace their setlists and keep audiences in a frenzy. I’ve watched Mark’s eyes look steadfastly at a crowd, through bright lights and thick smoke, while telling the same sad stories he’d told the others: “You look like rain.” “Candy says she wants me with her, down in Candyland.” “She said, ‘Fill it up and send it back.'”

The Internet is sometimes a terrifying place. So many semi-anonymous voices make so much noise, all clamoring desperately for attention, for real-time appreciation, for responses that can be numerically valued. Loving an artist like Mark Sandman feels like a completely different feedback loop than that. One where songs are shared, memorized, and celebrated in sweaty, dingy communities like record shops and nightclubs. Where noise, feedback, and cheering become their own symphony, a combined din that sees people coming together to be lovesick, sad, hurt, and healing together.

Sandman was a product of that era, and the Internet (meaning, its many denizens and the sites that let them share and host songs and videos) did the next best thing for me. The Internet waited for me to catch up as an adult, as someone willing to face emotions and grief, and made sure I had a front-row seat to Sandman’s sermons about all of it when I was ready. So, thanks for that, Mark and friends.

It’s the kind of thanks that easily gets lost in copyright debates, where estate handlers clutch pearls and giant companies battle the possibility of expiring copyright laws. My story is but one anecdote (and one that doesn’t take Sandman’s surviving family and record labels into account). I don’t mean to flatly beg for all leaked music to be free, with no compensation or attribution. I just mean to say that this artist’s online collection has made grief a little easier for the hundreds who subscribe to his memory. Whether your own artistic grief lands with Sandman or any other artist given a new lease on life via the Internet, I invite you to join me.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1531003