Sharks have been swimming and hunting in the world’s oceans for 450 million years, and though their numbers have recently declined because of human activity, they’re still with us. But the world once had many more, and many more varieties of, the large marine predators compared to today. In fact, new research published in Science suggests that 19 million years ago, the vast majority of sharks and shark species died off. We don’t understand why or how this large extinction event occurred.

“Sharks have… weathered a large number of mass extinctions. And this extinction event is probably the biggest one they’ve ever seen. Something big must have happened,” Elizabeth Sibert, one of the authors of the paper, told Ars.

Sibert is a Hutchinson postdoctoral fellow at the Yale Institute for Biospheric Sciences, and she was a junior fellow in the Harvard Society of Fellows for the initial phases of this research back in 2017.

Back then, the team analyzed ancient sediment core samples, one from the South Pacific and one from the North. The International Ocean Discovery Program collected these samples in 1983 and 1992, but the material they contain dates back hundreds of millions of years. Each centimeter down on the cores represents a few 100,000 years back in time.

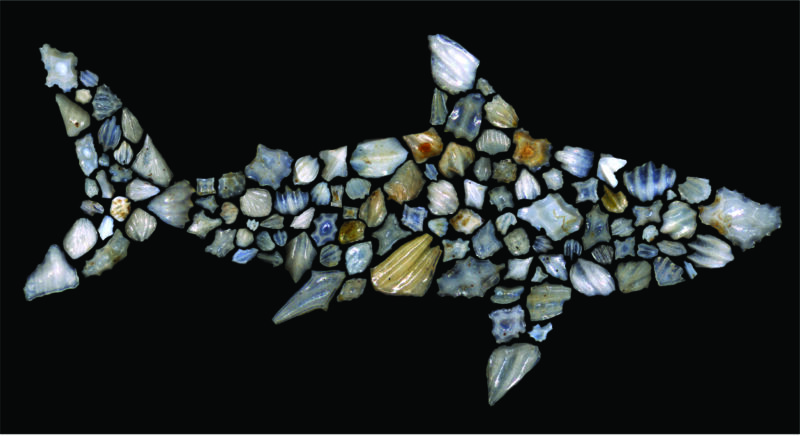

Embedded in the sample were 1,381 tiny shark scale, or denticle, fossils. The team looked at the raw number of scales and the different types of scales that appeared in the different layers of sediment. “Dermal denticles offer an incredible window into the past of these ancient and elusive marine predators and thus the state of ocean ecosystems through time,” Leah Rubin, another author on the paper, told Ars.

Sharp decline in sharks

Prior to 19 million years ago, the researchers found a wealth of shark biodiversity and abundance. But after that point, they saw a stark decrease in the number of scale fossils and fewer varieties of them. In all, there was a 90 percent decrease in terms of raw population and a 70 percent decrease in species diversity. Sharks never really recovered to the dizzying highs of pre-history.

Though the sediment cores are from the Pacific, Sibert suspects that the team’s findings could hold true for other parts of the deep. According to Sibert, some core samples from the Atlantic Ocean show an abundance of shark life 30 million years ago. There are also more recent samples, from only a few million years ago, that similarly show a decline—but so far, there are no Atlantic samples from the timeframe of the extinction event.

Whatever led to the shark-pocalypse is still unknown. The oxygen and carbon isotopes—which are used to reconstruct what the temperatures and carbon cycles were like in the past—don’t show anything amiss. In fact, they were so normal that researchers haven’t spent much time studying 19 million years ago. However, Sibert noted that with more research and more sediment samples, the mystery is quite likely to be solved.

“One of the challenges with this particular bit of research is ‘what happened to the sharks at this time and why was there this massive die-off?’ The answer is ‘we really don’t know right now,’” she said, adding that the team hopes to look into how the die-off impacted other oceanic species.

We’re gonna need a bigger data set

According to Seth Finnegan, associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley’s department of Integrative Biology, the paper’s findings are intriguing, but they rely on only two samples. He noted that it is also possible that the large shark die-off only happened in the Northern and Southern Pacific. But that’s probably not the case, as something affecting one part of the ocean will usually affect others, he said.

All the same, Finnegan noted that to get a clearer picture of what happened 19 million years ago, more samples from other parts of the ocean, and places closer to shore, would be helpful. “There are multiple levels of uncertainty here, but it’s a very interesting and striking pattern. It’s not subtle,” he told Ars.

It’s too early to say how this research fits into our understanding of history, Finnegan said. But the study shows that sharks have been around for a long time and have seen some pretty staggering biodiversity swings. Future research into the impacts that this shark die-off had on other creatures could also outline the importance of shark conservation today. According to Finnegan, sharks are an essential part of their ecosystems, and having large swaths of them kick the bucket could produce impacts that we don’t yet fully understand.

“They tend to be very important apex predators in a lot of ecosystems, very important in regulating ecosystem structures,” he said.

Among well-studied species, stumbling onto a large extinction event is quite rare, Finnegan said. However, considering fossilized shark denticles have not been thoroughly studied relative to other fossils, it’s perhaps not that surprising to come across a previously undiscovered die-off.

There could be other extinction events throughout history that scientists simply haven’t discovered yet, Sibert told Ars. Even today, researchers might come across some other ancient surprises. For example, her team began the work looking for background information on fish and sharks around 80 million years in the past—instead, they came across a doomsday event for the ocean predators.

“To me, that’s something that’s really fascinating and really exciting. If you go looking, there are probably all sorts of things we don’t know about the Earth and its history.”

Science, 2021. DOI: 10.1126/science.aaz3549

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1769303