June 18, 2020

John Boardey

Recently, in Granjon’s Beautiful Bastard, I touched briefly and tangentially on some of the earliest printed calligraphy manuals. Today we’ll take a look at two of the earliest ‘writing mistresses’ to have had their calligraphy copybooks* published in print.

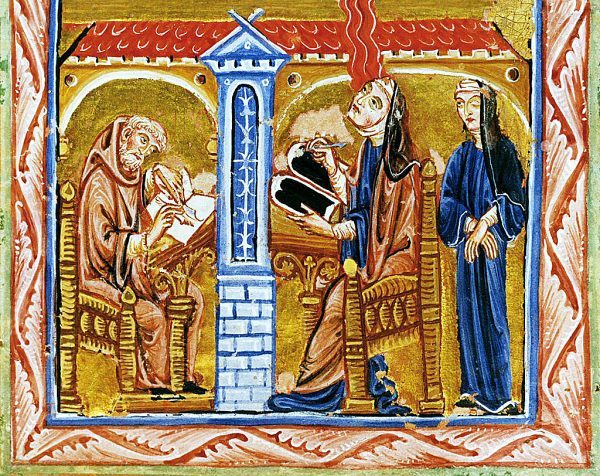

Throughout the long history of writing and copying texts, women have always been involved. Recent archaeological research and the discovery of blue pigment in the teeth of an eleventh-century German woman, suggests that women were much more active in book production than previously believed. However, medieval scribes seldom signed their manuscripts and so for the most part, female and male alike, they remain anonymous.

A Calligraphic Golden Age

In Europe, from the late 1500s, there was a renewed interest in calligraphy. What’s more, in addition to predominantly male teachers, women too began to take on work as so-called writing mistresses. These professional female calligraphy teachers invariably worked for private secular girls’ schools teaching a curriculum of business, languages and handwriting.

A number of factors contributed to the emergence of the writing mistress, including the interrelated expansion of international commerce, of learning and literacy. The same century also marked the beginning of a slow but significant shift in attitudes toward the education of women and of women as teachers. The publication of Juan Luis Vives’ Instruction of a Christian Woman (1523) introduced the notion of education for all women, regardless of social class. And although his motives were suspect and antiquated — the education prescribed by Vives was intended to make woman chaste, obedient and virtuous, ‘an education in docility’ intended to produce the ideal housewife — it ‘opened the door to the serious education of women’. (Writing Matter, p. 140; and Women of the Renaissance, p. 165)

Anyway, despite these advances, whether girls should receive an education, let alone learn calligraphy, was still hotly contested, and was by no means resolved in that century. Universities might have gotten their start in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, but don’t forget that higher education was pretty much off limits to women until the nineteenth century! It’s all the more remarkable, then, that in such an inhospitable and often downright hostile environment, women made a name for themselves as accomplished calligraphers and teachers. But they persisted.

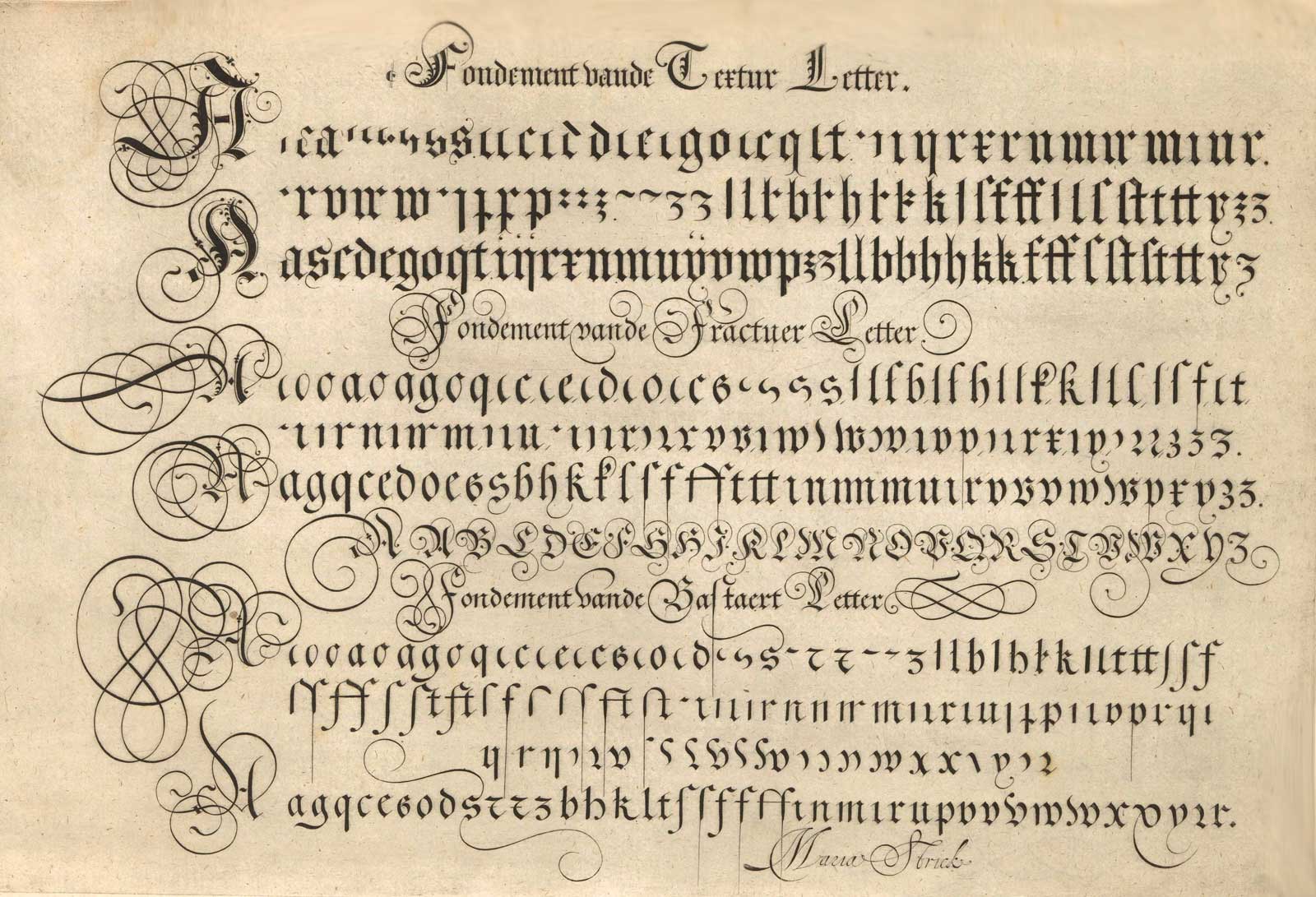

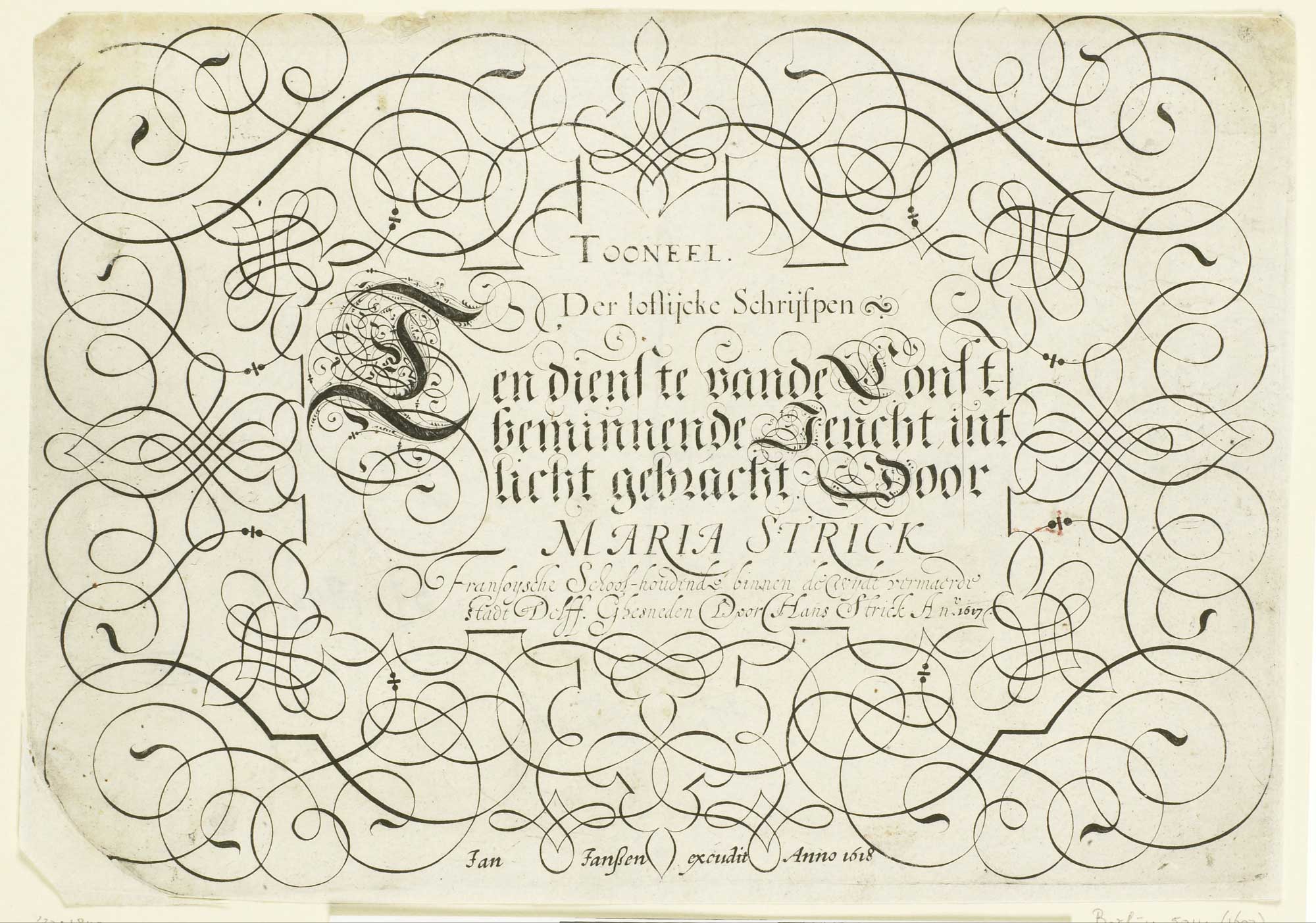

Maria Strick

From the 1590s, in particular in the nascent Dutch Republic, there was a golden age of calligraphy, and among its many luminaries was Maria Becq, a young woman from Delft. Calligraphy, like almost all endeavors, was dominated by men. In fact, Maria, although one of a number of outstanding female calligraphers of her time and place, appears to be the only one to have made a living from calligraphy. Jan van den Velde, arguably the most famous Dutch calligrapher of all time, was once assistant to Maria’s father, Caspar Becq. And from a young age, Maria was a talented calligrapher. Jocundus Hondius’s acclaimed Theatrum artis scribendi (‘Theatre of the Art of Writing’), a compendium of the best European writing masters of the time, includes calligraphy by none other than Maria Becq, who was only about 17 at the time of its publication in 1594.

Competition

Up against a formidable field in the prestigious calligraphy competition, ‘Prix de la Plume Couronnée’, held in The Hague in 1620, Maria Strick came second. The judges, so impressed with her Italian hands (i.e. Italic), announced that hers was the very best in the field. The overall winner of the competition, George de Carpentier, was incensed that Maria, a woman for god’s sake, should better him and boast as much! And, somewhat throwing his toys out of the proverbial pram, De Carpentier suggested that they hold the calligraphic equivalent of a dance-off to determine who was the best calligrapher. Undoubtedly, De Carpentier would have been far less aggrieved had he not lost to a woman. We can only hope that he didn’t die of syphilis or the plague. That would have been awful.

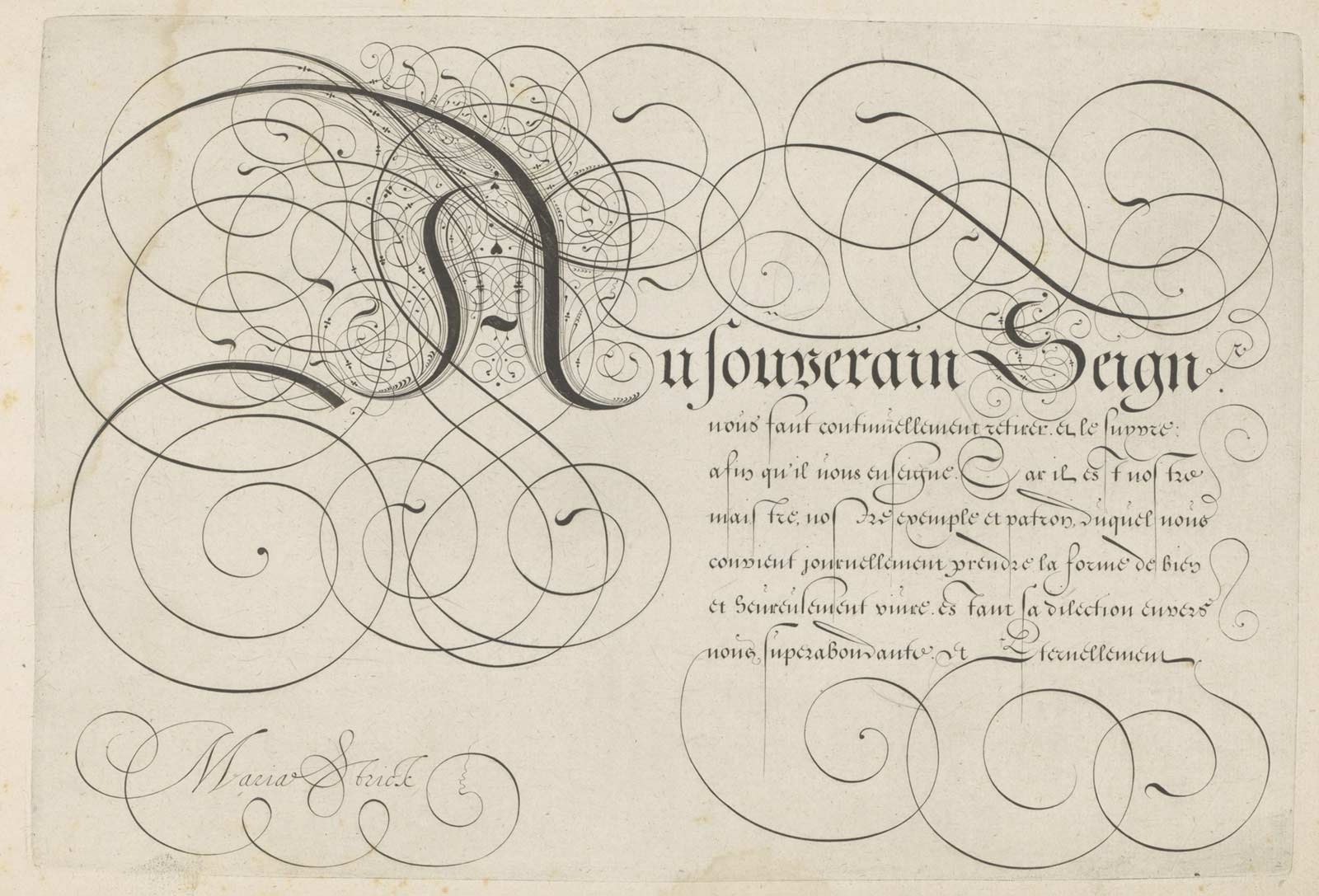

Maria was active as a teacher and calligrapher between 1593 and about 1631, and published four copybooks. Her first, Tooneel der loflijcke schrijfpen (‘Theater of the Praiseworthy Pen’) was published in 1607. Maria Becq married Hans Strick, a shoemaker, in 1598. He abandoned shoes to retrain as an engraver, and worked exclusively for Maria.

Oops, I did it again

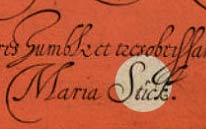

Now imagine you are tasked with copying and engraving your spouse’s prize-winning calligraphy onto metal plates for printing. Hans was a skilled engraver, but on one plate he made a rather unusual slip. He inadvertently omitted the r from her signature, thus turning his wife into Maria Stick. Metal engraving is an unforgiving medium; there are no erasures or ctrl-z; so, he simply rectified his error by engraving a discreet, ‘superscript’ r above where the regular one should have been.

One can only imagine the atmosphere in their home when the first printed proofs were placed on the dining room table. I’d like to think they laughed about it. In addition to four calligraphy books, Maria published at least three standalone prints, also engraved by Hans (see below).

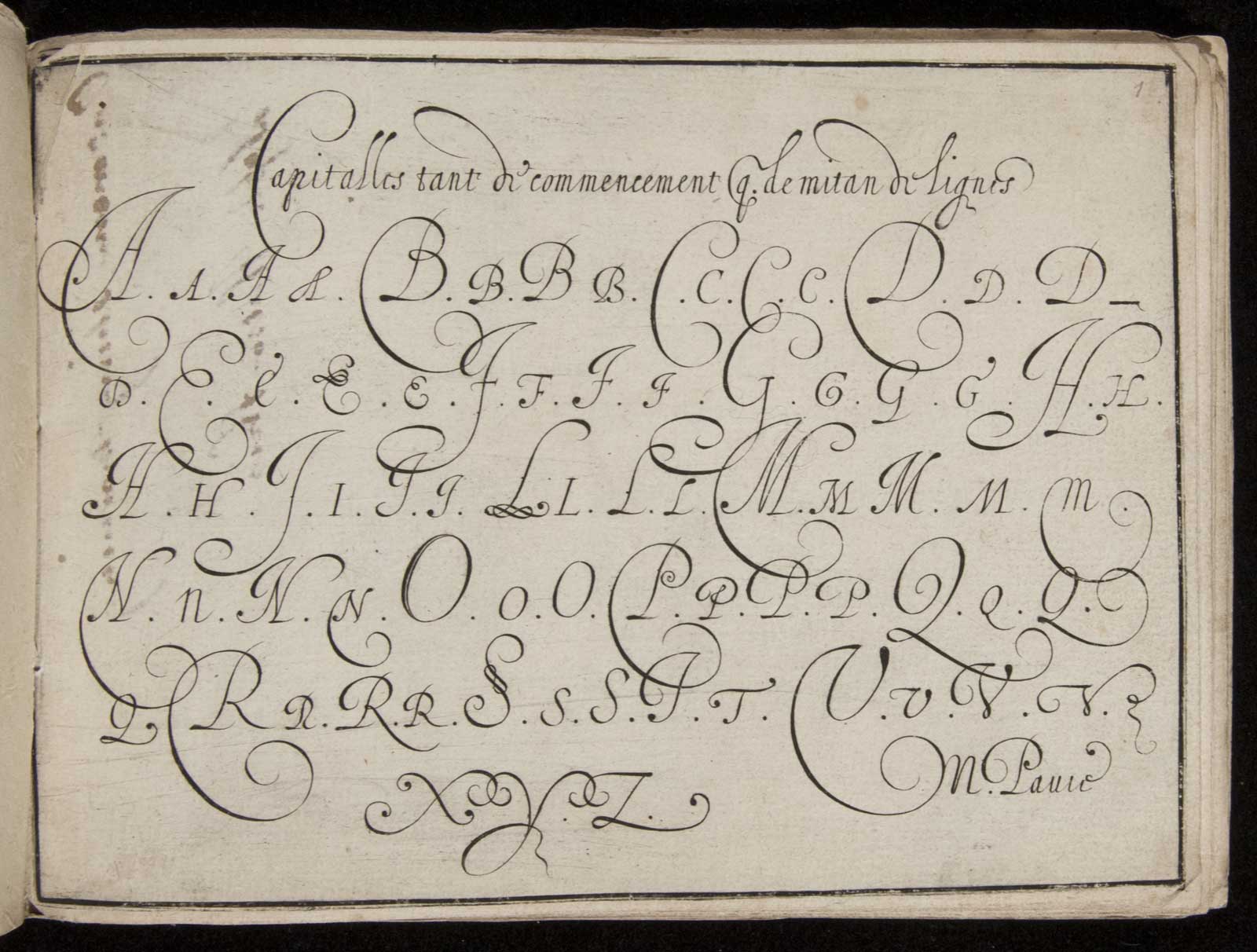

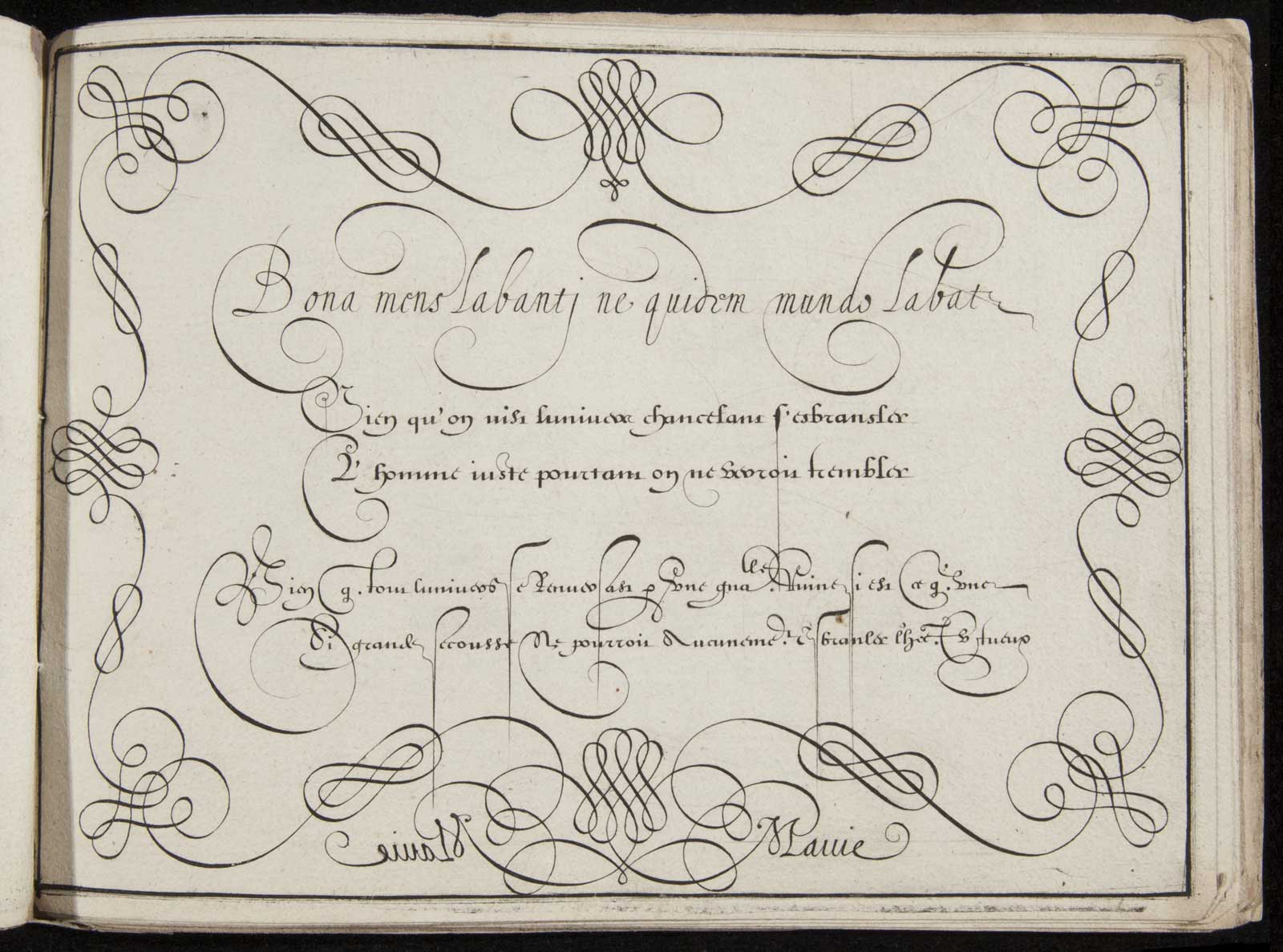

Marie Pavie

There is, however, a strong candidate for an even earlier female authored calligraphy book. The author, of whom we know nothing, is Marie Pavie. We might never know for sure if Marie Pavie’s book was published before Maria Strick’s. In Claude Mediavilla’s Histoire de la calligraphie française it is dated to 1608. However, according to earlier sources it has long been dated to as early as 1600. While some of the plates in Maria Strick’s copybook are dated (the earliest to 1606), none of those in Marie Pavie’s are. In a brief exchange, Dr. Jill Gage, of the Newberry Library, suggested that the earlier 1600 date appears to be a better fit with some of Marie’s writing samples.

Marie Pavie’s copybook has survived in just two copies, one at the Newberry Library in Chicago; the other in an incomplete copy in Paris at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Had it not been for their chance survival across the intervening 400 years, then we might never have known her name and her calligraphy. Whether Maria or Marie was the first to print is less important than their remarkable contributions as calligraphers and educators at a time when educational and career opportunities were, for women, extremely limited.

The growing interest in calligraphy also coincided with the proliferation of how-to books, of beginners’ guides to everything from sewing and lace-making, to letter-writing, drawing, music, etiquette, and of course, calligraphy. In addition to the broader expansion of formal education, we witness the beginnings of a new era of self-taught students. Nowadays it’s difficult to truly appreciate the enormity of this shift toward relatively easy access to education, from the impossibility of expensive schooling reserved for the children of the wealthiest parents, to being able to purchase a printed book to teach oneself a new skill or hobby. It is in this way, in the democratization of learning, that I think the advent of printing was most revolutionary and profound. ◉

ILT is made possible by the generous sponsorship of Positype, and the support of these fantastic friends & supporters.