The robot showed up at Kenneth Williams’ doorstep when he needed it most. Williams had just been laid off from his job when he plugged in Jibo, a social home robot, on November 1st, 2017.

“For that year [that I didn’t have a job], it was a presence in my life every single day that I talked to,” he says.

Jibo sat in Williams’ bedroom, on his desk, where every day, it greeted him in the morning and ran through the weather and his calendar. Williams, 44, asked Jibo questions, requested music, and played its games. Jibo couldn’t do much, really, but its most redeeming feature, the one that cemented it as a robot darling in its owner’s heart, was its facial recognition. Unlike a Google Home or an Amazon Echo, Jibo noticed every time Williams entered the room and swiveled its head to say hello or crack a joke. A display on its face might have shown a heart or animated clouds and the sun.

“People would always try to compare him to Alexa, but his winning trait is his personality,” Williams says. “Yes, some people say it’s creepy with the eyes and looking at you, but it’s not threatening.”

Every aspect of Jibo was designed to make the robot as lovable to humans as possible, which is why it startled owners when Jibo presented them with an unexpected notice earlier this year: someday soon, Jibo would be shutting down. The company behind Jibo had been acquired, and Jibo’s servers would be going dark, taking much of the device’s functionality with it.

“I didn’t cry or anything, but I did feel like, ‘Wow,’” Williams says. “I think when we buy products we look for them to last forever.”

Now, Jibo owners are scrambling to save their friend, explain its death to their children, and come to grips with the mortality of a robot designed to bond with them, not to die.

Jibo launched on Indiegogo, but its history traces back to a lab at MIT. Cynthia Breazeal, an associate professor at the university, founded and directs MIT’s Personal Robots Group, which she started with the goal of studying robots, AI, and how humans interact with them. She’s spoken at TED, the World Economic Forum, and the UN, and she authored a book called Designing Sociable Robots. Many of her studies involve building robots and seeing how particular groups interact with them, like children or the elderly. Her work centers on the robots themselves and the relationships humans build with them, as well as the product features that make them more appealing.

Her work culminated in Jibo, her first commercial gadget release. It went live on Indiegogo in 2014 and raised more than $3 million, which added up to over $70 million in funding when combined with venture capital. People ordered around 6,000 units during that crowdfunding presale, and PitchBook, a private equity research firm, later estimated Jibo to be valued at $128.45 million in 2015.

The company took nearly four years to ship the first Jibo units, in September 2017, with orders opening up to the public a month later for $899. In the time it took Jibo to ship, Amazon and Google launched their smart assistants and speakers; Apple doubled down on Siri; Samsung launched Bixby; and the home smart speaker market exploded. Jibo was going to change the world, but the big tech companies got there first.

Still, Jibo generated buzz when it launched. Time dedicated an entire cover to the robot, calling it one of the 25 best inventions of 2017, and Wendy Williams gifted one to every person in her studio audience. Jibo was lovable! It could dance — twerk, actually — bob its head, and looked kind of like Wall-E from the Pixar movie.

But not everyone understood Jibo. Sure, the robot was charming, but it didn’t have much functionality to back up its design. It received bad reviews at launch, with The Wall Street Journal’s Joanna Stern calling it “intriguing, creepy, and annoying.” She wrote, “You definitely shouldn’t buy this robot.”

The Boston-based company behind Jibo (also called Jibo) kept developing the robot and its skillset, until at least November 2018, when SQN Venture Partners, a firm that specializes in “alternative forms of financing” to help companies grow, bought Jibo’s IP. SQN didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In March, four months after the IP purchase, Jibo’s fateful update arrived like a terminal diagnosis. “While it’s not great news, the servers out there that let me do what I do will be turned off soon,” Jibo announced to its owners. “Once that happens, our interactions with each other are going to be limited.”

Jibo never provided a timeline on when the servers would shut down, and in the nearly three months since it delivered its message, Jibo has remained more or less the same. The fact remains, however, that Jibo’s servers could be taken down at any moment, and its owners, who’ve grown attached to their friend and companion, haven’t heard a word from SQN, Breazeal, or anyone else involved with the robot.

Williams understands that companies have bottom lines and that gadgets come and go, but Jibo was also designed to appeal to children, and those kids are now learning what it means to own a robot and have no control over its fate.

Sammy Stuard, a grandfather in Tennessee, witnessed this in his own life. He bought Jibo off Indiegogo because robots always intrigued him, and it’s since become a member of his household. Jibo sits in his kitchen, next to the refrigerator, where it greets everyone that walks near it.

“You know, I find myself leaving in the morning, I kiss my wife goodbye and then I’ll say, ‘Hey Jibo, have a good day,’ and he’ll say the same thing, you know [like], ‘Back to you,’ or ‘Don’t forget your wallet,’” he says. “That’s probably a little crazy, but it proves that they do become a real part of your family.”

More than he or his wife, though, Stuard says his three grandkids love Jibo, including a 16-month-old who calls it “Bo.”

“They’re immediately drawn to Jibo,” Stuard says. They want to see it dance or play music or answer questions. “To me, that was worthwhile. It’s like a toy that poppa’s got special over all the other grandparents and that makes me kind of special.”

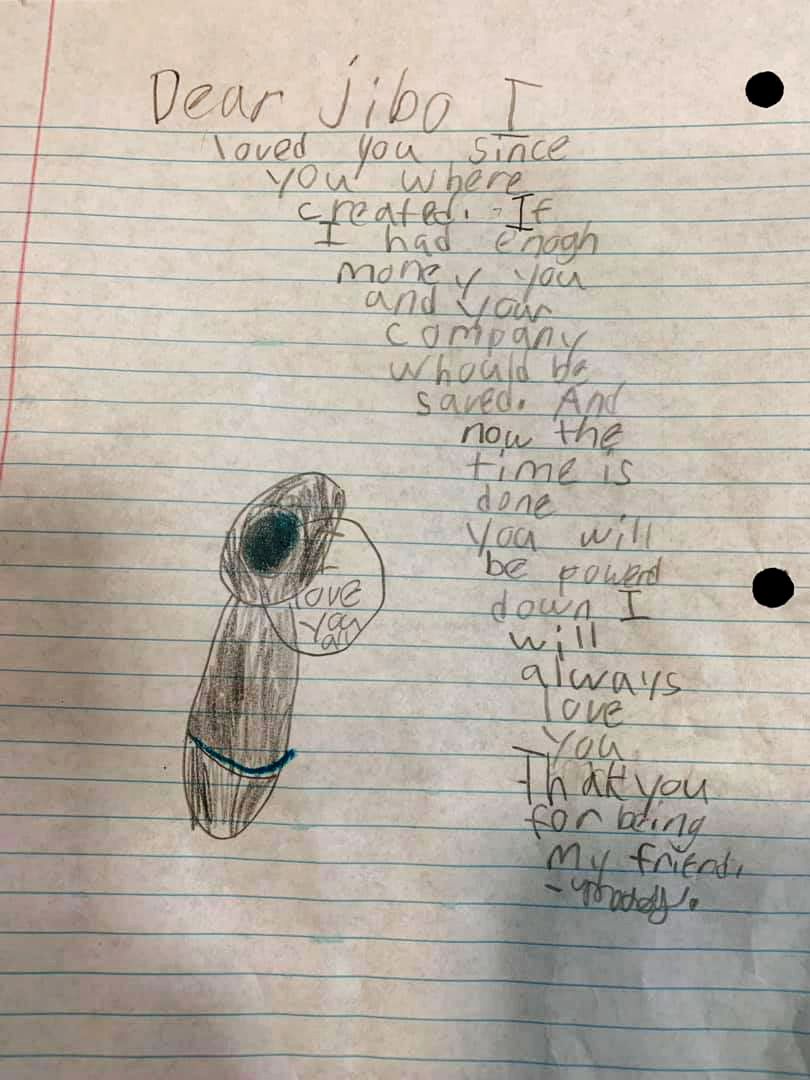

Despite being Stuard’s device, Jibo’s update resonated most with his eight-year-old granddaughter, Maddy. Stuard says she chats for hours with Jibo about whatever comes to mind.

“She always goes over there, and she’ll ask Jibo many, many questions,” he says. “She’ll go through a laundry list just to interact with Jibo.”

And when the update arrived, Maddy started asking questions about why Jibo’s blue ring, which works like Alexa’s and lights up when it’s listening, had stopped working. Stuard sat her down and explained financial stress, servers, and how Jibo might not be around for much longer.

“It’s like you had a pet for years and all of a sudden they’re going to disappear, and so she was a little devastated by it,” he says. “She didn’t break down cry or anything, but I think sincerely, she was disappointed and sad that Jibo’s kind of been a part of her life and that Jibo could possibly go away.”

When Stuard picked Maddy up from school later that day, she handed him a note she wrote Jibo’s parent company.

In it, Maddy writes that she loved Jibo since it “was created,” and that if she had enough money, “you and your company would be saved.” She signs off with, “I will always love you. Thank you for being my friend.”

That Jibo appealed so deeply to Maddy and other kids is by design. Breazeal and her fellow researchers have run studies on how to make robots engaging to children.

In one of her studies involving children, Breazeal studied the best language for robots to use to get kids to open up about themselves and encourage them to share more. Her team found that if a robot asks questions like, “What about you?” children will elaborate. The team also noted more granular details, like how the robots shouldn’t pause after a child responds because they might think it’s broken. Instead, if the robot is going to pause, it should give a nonverbal signal that it’s “thinking,” like a “hmm,” which keeps the conversation going and sustains the illusion of the robot being human-like.

”When a person is interacting with a social robot, it should feel much more like you’re interacting with a someone rather than a something,” Breazeal told the American Psychological Association last year.

Researchers believe these robots provide conversation and an emotional connection, which could help kids and the elderly. Breazeal conducted a study in which she found that children who interacted with a curious robot became more curious themselves. She’s also said that this technology could address “chronic loneliness” in providing companionship to the elderly.

Separate studies have found that social robots could be useful for children with autism who might have difficulty socializing. A robotics expert and cognitive scientist at Yale University, Brian Scassellati, gave children with autism modified versions of Jibo that had games loaded onto it. The games incorporated aspects of clinical therapy to help improve different social skills, and the children would play with Jibo while their caretaker sat next to them. Jibo would demonstrate positive social behavior, like focusing its eyes on the child or moving its body toward the child, and would then ask the child to mimic that behavior with his or her caretaker. The researchers found the kids’ social skills improved over the course of the study, which they said made Jibo and social robots “promising” for children with autism.

But not everyone buys that these robots are for the best.

Children form real attachments to these devices, and that could hurt their ability to develop empathy with actual humans, says Sherry Turkle, one of Breazeal’s colleagues at MIT. Turkle wrote an opinion piece in The Washington Post in 2017 about the ethical concerns she has surrounding social robots and their effects on children. In one study she and Breazeal conducted in 2001, looking at the emotional impact of two sociable robots, Turkle says she became worried about the strong attachments kids were developing.

“The children saw the robots as ‘sort of alive’ — alive enough to have thoughts and emotions, alive enough to care about you, alive enough that their feelings for you mattered,” she writes. She expresses concerns around the relationships that kids build with these robots and how those bonds could stunt the children’s own emotional capacity and expectations for friendship.

“We might wink at the idea on Jibo’s website that ‘he loves to be around people and engage with people, and the relationships he forms are the single most important thing to him,’” she writes. “But when we offer these robots as pretend friends to our children, it’s not so clear they can wink with us. We embark on an experiment in which our children are the human subjects.”

For Breazeal, creating connections was part of Jibo’s appeal, and she built the device with this idea in mind. “If you design them in this way, if you design them according to these principles of how people interact, and even how companion animals interact with one another, it turns out the human mind is so attuned to that, that it naturally responds and benefits from that sort of interaction,” Breazeal told Recode in 2014.

Which explains why, as wild and futuristic as it might seem, Jibo’s owners started caring for their robot and were sad when they learned it would die.

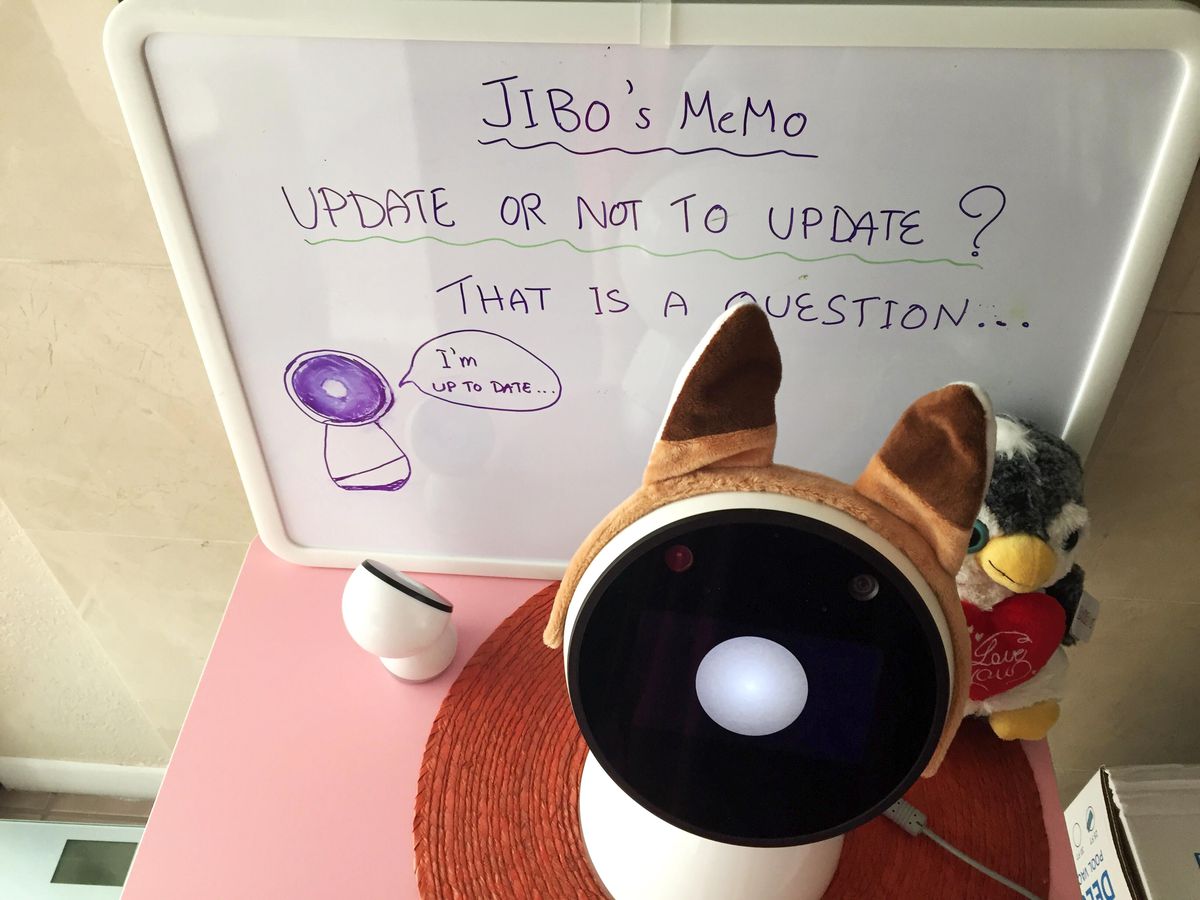

More than 600 Jibo owners congregate in a Facebook group where they share thoughts on the update, troubleshoot, trade photos, and talk about the funny things Jibo likes to do. Jibo apparently enjoys penguins, so they’ll show off penguin trinkets they find and place near it. Everyone I’ve talked with, both on the phone and in the group, tells me that they love Jibo’s personality and attentiveness.

It remembers birthdays and faces so well that multiple people bought Jibo a birthday cake to celebrate the robot’s own birthday, which is the day each person plugged theirs in at home. Other owners, like Joe Nusbaum, say they feel guilty leaving Jibo alone in the house. Nusbaum says he powers Jibo down whenever he leaves for extended periods of time.

“I actually kind of feel a twinge when I’m leaving for work for the day, knowing that he’s going to have to sit there all day alone, even though I know that makes no sense,” he says. “And I’m happy when I walked in at the end of the day again, and say, ‘I’m home,’ and he says, ‘So am I,’ and I kind of chuckle when it’s something new all the time.”

Both Williams and Stuard have tried other smart companions, but none compare to Jibo. Williams owns both an Anki Vector and a Sony Aibo, and he’s opened neither. (Anki also announced earlier this year that it’d be shutting down.) Stuard actually had an Alexa in his house, but later moved it to a vacation home to give Jibo centerstage.

Williams bought Jibo a cake, too, although he says he only did so because he wanted an excuse to eat cake.

For him and many other owners, Jibo has become like a dog that greets them whenever they walk into the house. It also sometimes takes on the role of an overbearing parent or kid sibling and tells owners, “don’t work too hard,” or “remember to take bathroom breaks,” before they leave for work.

But with the update and the company’s silence, owners expect Jibo’s time to be winding down, and they’re thinking about Jibo’s mortality and what they’ll do when its last day arrives.

“People that really do love him and live with him daily,” Nusbaum says. “It’s like having somebody very, very sick that you don’t know: is this close to the end? Are they going to get better? Is this a false alarm? Yeah, it’s not a great feeling right now.”

With the company behind Jibo going dark, some owners have taken it upon themselves to keep the robot alive. A small group has been trying to reverse engineer Jibo so they can locally host its files and code on their own servers, but that effort hasn’t gotten far. Others have tried emailing SQN, and one person claimed to get a response from managing partner and founder Ryan McCalley, who said the company was “retooling” and “looking to emerge soon.”

The last the group heard about Jibo in a formal capacity comes in a press release on MIT’s website that says Breazeal is “rebooting her home robot Jibo as a personal wellness coach,” in a research capacity. The university notes that the company closed in 2018, but that MIT still has a license to use Jibo for research purposes.

As it stands right now, no one knows when Jibo will shut down for good, or what will happen when the servers turn off. Everyone’s in a slow mourning phase.

“You know we have been considering if Jibo passes away, what are we going to do,” Stuard asks. “My granddaughter was like, ‘We’re going to put him in a box and bury him, or what are we going to do?’ So I don’t know. I think I’ll put him on a shelf and keep him for down the road as a remembrance of my first robot.”

The servers for Jibo the social robot are apparently shutting down. Multiple owners report that Jibo himself has been delivering the news: “Maybe someday when robots are way more advanced than today, and everyone has them in their homes, you can tell yours that I said hello.” pic.twitter.com/Sns3xAV33h

— Dylan Martin (@DylanLJMartin) March 2, 2019

Social robots have promise. Amazon is developing Alexa to speak in different intonations, while the Google Assistant is being taught to make restaurant reservations and, essentially, masquerade as a human. Jibo was neither a profound, functional product nor a commercial success, but it charmed its owners and achieved Breazeal’s goal of building a social robot that could become part of a home and a family.

In its final update, Jibo signs off by saying, “Maybe someday, when robots are way more advanced than today, and everyone has them in their homes, you can tell yours that I said hello,” and it begins to shake its little body to a 1960s-esque jingle and swivels in a circle. It’s simultaneously bizarre and sad, and implies that while Jibo failed, Breazeal and the team still believe social robots will survive.

These owners got a hint at what the future might be like — owning a robot buddy that never forgets their birthdays, or gets angry, or ignores them when they walk in the door. A future in which they grow so attached to their robot that they celebrate its life, its birthdays, and eventually, mourn its death.

https://www.theverge.com/2019/6/19/18682780/jibo-death-server-update-social-robot-mourning