Image credit: Robert Couse-Baker

Before all else, gratitude to every delivery person, whether in-house or third party, doing the essential work of keeping households safer and supplied in these times. I’m dedicating today’s column to the manager of a nearby Sprouts grocery store who personally drove my order to my door when an Instacart driver just couldn’t get the job done.

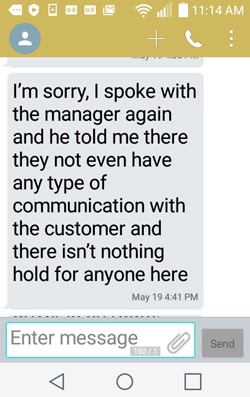

If your business or clients are weighing whether to fulfill delivery in-house or partner with a third party, my small experience is an apt footnote to the huge, emergent debate over last-mile fulfillment options. I’d searched all over town for scarce potatoes, finally arranging by phone with the local Sprouts market to hold their last two bags for me one morning, and texting the Instacart driver about where the spuds were being held. Next:

For whatever reason, the driver chose not to retrieve them, claiming the manager told them there was nothing being held for me. Not knowing whom to believe, I phoned the manager who confirmed the driver had never asked for the potatoes and, to my astonishment, told me he was going to bring the groceries to my house right away, himself.

“I feel really bad about this,” he said. “Sometimes Instacart’s drivers just go so fast, they don’t do a good job. It’s really important to me that my customers get good service and feel good about our store, especially with this hard time we’re all going through.”

And that’s the crux of what has suddenly become a pressing issue for millions of local businesses, as well as all local search marketers who draw a through-line between reputation and revenue.

Today, we’ll:

- Stack up the pros and cons of in-house vs. third-party delivery

- Interview a software engineer who has been on the ground with this evolving narrative of critical choices

- Excerpt the revealing comments of a former head of development at Grubhub.

- Plan SEO and marketing strategy for competing with corporate delivery

- Examine the welfare of and best options for drivers

- Help your brand or clients make a better-informed delivery decision

A piece of the pie

On March 15, 2020, downloads of Instacart’s app shot up 218% over their normal daily average. Restaurants, grocers, and a wide variety of retailers have spent the past two months forging paths from shelves to customers’ front doors to meet demand. While initial implementation may have been a scramble for the state of emergency, we’re getting to the place where it’s time to talk long-term plans.

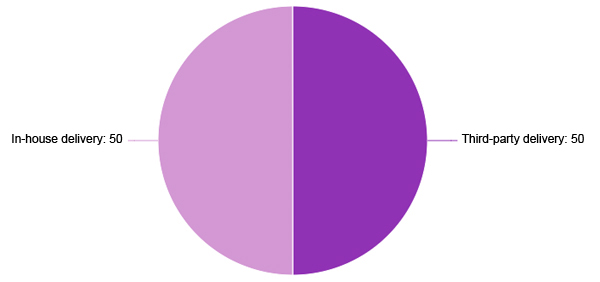

I recently surveyed a group of several hundred local business owners and local search marketers to ask whether they intend to permanently offer home delivery. Of those who answered “yes,” I asked whether they would be staffing up an in-house delivery fleet or outsourcing to a third party, like Instacart, or Postmates, GrubHub, or Uber Eats. I found it amazing that my survey group was split right down the middle:

Clearly, there’s an even divide between brands that expect to manage the entire customer experience from start to finish, and those whose circumstances are causing them to entrust the last mile to a workforce they can’t directly control. I wondered if the 50/50 split represented settled decisions or indecisions and, also, how my pie chart might look a year from today, when all parties have had more time for implementation and analysis.

For now, we’ll start by examining another type of pie with a technician who experienced a pizza company shifting from in-house to third-party delivery.

A tale of cold pizza and ghosting drivers

My friend is a software engineer who worked on last-mile delivery integration for a headlining US pizza startup, and whose anonymized takeaways serve as a stunning cautionary tale. The engineer tells it this way:

“We started with an in-house delivery fleet, with two drivers assigned to each company vehicle and each vehicle servicing a radius of approximately five miles. Delivery times were under fifteen minutes with this setup, and we had a ton of very happy customers. Leadership then decided to outsource delivery to a well-known third party.”

Take note of what happened next.

“Average delivery time shot up to sixty minutes for peak dinner hours, and holidays were especially bad. One Hallowe’en, it was taking three hours for customers to receive their dinnertime pizza because of driver availability. The third party can’t simply add more drivers as they have no control over when drivers sign onto their platform, but with an in-house fleet, you can plan for high demand and increase staffing. And, instead of having an in-house driver waiting with their truck on the premises to take a delivery, you have to wait for the third party to assign a driver (between 5-30 minutes), wait for the driver to arrive (another 5-30 minutes), and then, finally, deliver. You’d sometimes see deliveries assigned to third-party drivers twenty miles away who would end up ghosting because they don’t want to be bothered with the long drive.”

As for technical concerns, the engineer told me:

“Technically, the third-party service was not reliable. I had to deal with a lot of random bugs in their API, as well as constant service interruption, and they had very poor engineering support for their API. This might not be true of all third-party services, of course.”

And, finally, here’s how the engineer summed up the impact of this on customers:

“The third-party delivery fleet wasn’t just inefficient in terms of time, but often, they didn’t have the proper bags to keep the pizzas warm. Customers waiting a long time for cold pizza will obviously lead to dissatisfaction. In-house drivers care more about the product they’re delivering, in my experience. I’m convinced that, given the choice, customers would always prefer restaurants to have in-house delivery staff, but it’s hard to compete nowadays with the big name last-mile platforms. Some brands have taken a very public stance on refusing to work with third parties, and I’d like to see Google and Yelp roll out features to let customers know when businesses have their own delivery staff, because it can make such a difference for the customer.”

As a local SEO, I know that difference for the customer is going to show up in the reviews and word-of-mouth sentiment for any brand, and that, cumulatively, it could equal the brand building, maintaining, or shedding loyalty. Reputation can, quite literally, be the difference between solvency and closure.

Positive press for third-party deliveries

If there are so many potential negatives associated with outsourcing delivery, why do so many successful brands go this route? We’ve looked at some cons, but this shortlist of pros is illuminating:

- Third parties have their own, highly-visible, well-ranked directories of businesses they service. These websites are hard to compete with if you’re not included in them. Seen in a certain light, third parties can bring a business new visibility and new customers. More on this ahead.

- Third parties have ordering technology, logistics, drivers and either proprietary or driver-owned vehicles all ready to go, doing much of the heavy lifting. Not having to pay for a fleet of vehicles or directly pay the wages of drivers can impact brands’ initial, fixed, and ongoing costs. Concerns about insuring these drivers also belong to the third party, not the brand.

- Third-party reliance means the grocer can focus on groceries and the chef can focus on cooking, not delivery. For some brands, the challenge of becoming delivery experts is just too distracting.

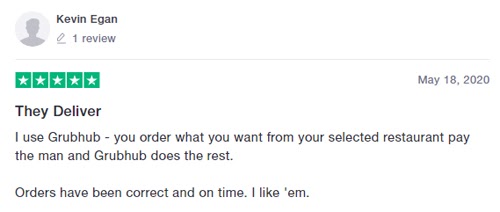

Many brands report having a good experience with major third parties. It’s important to read pre-COVID stories like these told by QSR’s Daniel P. Smith about companies that have relied on these providers for multiple years. Consider:

- The Buona family found that trying to focus on delivery detracted from the core operations of their 27-location Italian restaurant chain. In 2017, they turned the last mile over to DoorDash and were so pleased with the operation that they’re now also partnering with Uber Eats and Grubhub.

- Two years ago, the Habit Burger Grill launched a Postmates partnership in Northern California, and were happy enough with the arrangement to expand delivery from all 240 of their locations via Postmates, Doordash, and Uber Eats.

- Meanwhile, the 40-unit Just Salad chain has been using Grubhub since it launched sixteen years ago and praises their delivery time of under 35 minutes. At the same time, Just Salad also has an in-house delivery fleet. CEO Nick Kenner states that the company would prefer customers to choose the brand’s own delivery service, to “cut out the middleman.”

That last point is absolutely key to this story and to the third-party vs. in-house decision.

Cost issues with the middleman

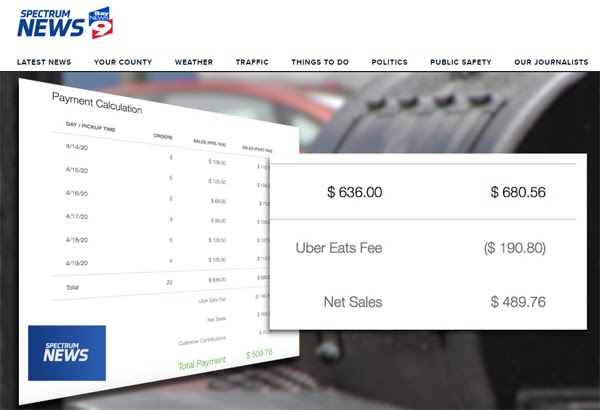

A narrative amplifying in volume during the public health emergency is that third-party delivery fees simply aren’t sustainable for small businesses. When BBQ restaurant owner Andy Salyards shared his Uber Eats bill with a local news station, I started doing some math.

- Salyards made $636.00 (pre-tax) selling 22 dinners.

- Uber Eats charged him $190.80 to deliver them.

- Salyards paid Uber Eats 30% of his earnings.

I found averages stating that a driver can typically make 2.5 deliveries per hour, though this depends on geography. Out of respect for the drivers, let’s hypothesize that Salyards is operating in a city that’s passed a $15 minimum wage and that he decides to employ in-house delivery persons.

- It would take 8.8 hours for one driver to make 22 deliveries.

- 8.8 hours x $15 an hour = 132.00.

- Salyards would be paying 20.75% for in-house delivery instead of 30% for third-party fulfillment for the same work in this dynamic. And obviously, where the minimum wage is lower, Salyards costs for in-house delivery would be far less.

On the face of it, in-house fleets look far more profitable than third parties, but here’s what my math doesn’t cover:

- Do in-house drivers use their own cars, or does the business have to make a major initial investment in a vehicle fleet?

- Who pays for gas/electric charging, auto maintenance, and liability insurance?

- How do you measure out the benefits of marketing your own brand by advertising on your company vehicles, vs. the loss of that opportunity because third-party vehicles don’t display your logo?

- What is the true cost to reputation, retention, and revenue when a brand loses control of the last mile of the customer experience? Is there an acceptable level of customer dissatisfaction caused by slower delivery times, lack of proper equipment, or ghosting drivers?

Each business has a unique scenario, and all of them will need to find customized answers to all of these questions.

Trust issues with the middleman

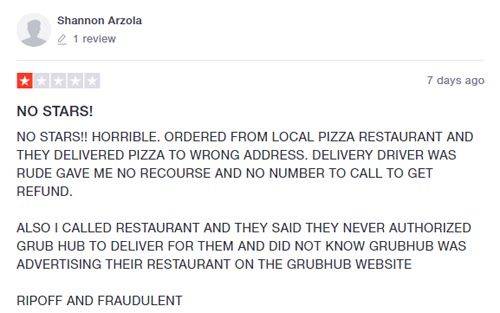

Customer service rules the viability of local businesses, and the best ones labor over every aspect of their operations to get things just right. Handing off the home stretch between the physical locale of the business and the customer’s front door is a phenomenal act of trust, and unfortunately, the local SEO industry has long been documenting the damages of trust misplaced.

To be completely honest, being set down amid Google, Yelp, and some of the major delivery brands, local business owners are gazelles amid a pride of lions. Some of the more infamous accusations against the lions over the past few years have included:

This last example, published by Ranjan Roy, received hundreds of frustrated comments, but it was the epic statement of Collin Wallace that glued me to my screen and deserves excerpting here:

“I was the former Head of Innovation at Grubhub, so I have seen the truth behind many of these claims first hand. Sadly, I invented a lot of the food delivery technologies that are now being used for evil…COVID-19 is exposing the fact that delivery platforms are not actually in the business of delivery. They are in the business of finance… like payday lenders for restaurants and drivers…

In the case of restaurants, these platforms slowly siphon off your customers and then charge you to have access to them. They are simultaneously selling these same customers to your competitor across the street, but, don’t worry, they are also selling their customers to you.

For drivers, they are banking on a workforce that is willing to mortgage their assets, like cars and time, well below market value, in exchange for money now. They know that most delivery drivers are simply not doing the math…If they did, drivers would realize that they are actually the ones subsidizing the cost of delivery.

Delivery platforms are “hyper-growth” businesses that are trying to grow into a no-growth industry. Food consumption really only grows at the rate of population growth, so if you want to grow faster than that, you have to take market share from someone else. Ideally, you take it from someone weaker, who has less information. In this industry, the delivery platforms have found unsuspecting victims in restaurants and drivers… Restaurants need to realize that they are now running e-commerce businesses and they need to act accordingly. Being proficient on Google, Yelp, Facebook and the dozens of other platforms is no longer optional, it is essential.”

Local SEOs will nod their heads over the need for local Internet proficiency, but it’s Wallace’s summation of the welfare of the drivers that strikes the most discordant note with me for relationships hinging on trust.

The Instacart driver who didn’t bother to bring me my potatoes sincerely worries me, not for my family’s sake, but for theirs. I already knew before reading Collin Wallace’s comments that some gig workers are living in their cars, camping in parking lots, and being forced to choose between safety and money. When you have a moment, brace yourself and read Quora threads in which gig drivers are arguing about how little they make. One of my own nieces is a gig worker, and she’s out there today as I write this column, trying to make ends meet and sanitizing her hands every five minutes. I’m worried about her every single day.

There are local business owners who treat their staff like family, and others who don’t. Where trust and your brand’s reputation are involved, a question that deserves to be asked is whether you can trust business partners and models that rely on a desperate workforce. How do you feel about your handcrafted pizza being delivered, not by employees whose wellbeing you directly influence, but by one in four drivers who are hungry enough to be eating the food they’re supposed to deliver?

As we look ahead with hope to a post-COVID marketplace, it’s worth taking the time to reflect on this question and how it relates to the quality of life in the community where you live and serve.

Dignified work for local delivery drivers

“Please leave it on the walkway. Thank you so much!”

“Okay. You take care!”

“Thank you. Stay safe! Take care!”

This is the socially-distant duet I now sing through my kitchen window several times a week with the essential delivery workforce. While we may not deserve a Grammy, I do feel every driver who has brought water, food, and goods to my family these past few months deserves more than recognition — they deserve a dignified workplace and wage.

If Grubhub’s former head of innovation is troubled by drivers subsidizing delivery costs in exchange for urgently-needed quick money, I am completely convinced that no local community is improved by reliance on an underpaid workforce with few protections, inadequate healthcare in time of illness, or housing insecurity. That’s the thing about seeing life through a local SEO’s lens: everyone is a neighbor, and people working in your city are your friends and family.

I would prefer my niece to find work with a local business with an in-house delivery fleet being paid a living wage. I’d prefer her workforce to have a union, too. This is the advice I would give both as an aunt and as a local SEO, but if you are a driver trying to evaluate your personal decision about where to work, these links are for you:

In recent memory, many delivery jobs were filled by teenagers — like my big brother at 16 — with a new driver’s license, a stack of pizzas, and a need for part-time income to purchase disco records and car insurance. Now, it’s mothers, fathers, and grandparents driving those long miles to bring absolute necessities to our doors.

If you work in delivery, my best advice to you is to study what Collin Wallace has said, study the market, and seek jobs with the best pay and best protections. You and your work are essential, and if you plan to work in delivery for the long haul, finding a union job, like the American Postal Workers Union, is likely to offer you the most protections and benefits.

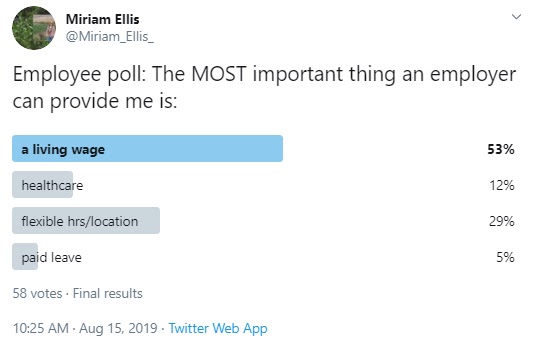

It’s not accurate to state that in-house drivers will automatically do a better job than gig workers for third parties. Many gig workers are going above and beyond to provide excellent service, day-in-day-out. But it’s only the in-house model that enables employers to ensure staff are receiving what they need to support themselves and support the brand. Last year, I did a very quick Twitter poll asking what it is that employees want most:

Employers: keep seeing that through-line between reputation and revenue when weighing the wages and working conditions you feel will make your brand most trusted by customers. Think of me, and my hunt for taters, and my feelings of uncertainty about trusting Instacart again, or any business that’s using them for fulfillment right now.

If you opt for in-house delivery, how will you compete?

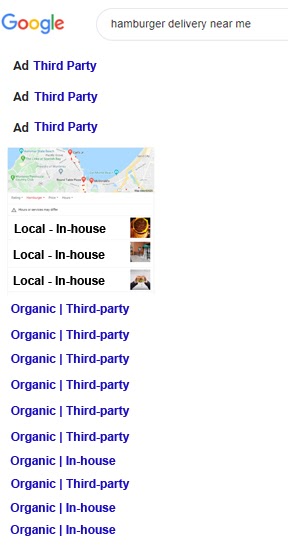

While competition will differ from market to market, here’s a very simple schematic of the typical set of Google results I’ve seen in my region for delivery-related queries, broken down into third-party vs. in-house delivery entries:

As referenced above, corporate delivery services have massive, authoritative websites and big ad budgets that allow them to gobble up visibility in Google’s SERPs (search engine results pages). In my schematic of 16 opportunities — which represents an actual SERP in my town for the keyword phrase “hamburger delivery near me” — 10 of the entries are being bought or won by brands like GrubHub, DoorDash, and Postmates.

If your business isn’t listed on the highly-ranked directories published by these services, and you lack a large paid advertising budget, a SERP like this leaves you just six places to compete for the customer’s attention. Here’s a basic three-part framework for how to compete:

1. Build your business for customers

If Collin Wallace is right in casting third parties as payday lenders and in the business of finance, your competitive advantage is to be in the business of customers’ needs. In practical terms, this means:

2. Build the strongest website you can

The usefulness, optimization, and technical quality of your website will all help you compete in both the organic and local SERPs. The more competitive your market, the more you will need to invest in implementing:

Moz’s Beginner’s Guide to SEO and Local Learning Center will get you well on your way to competitive wins. And double down in writing about the superlatives of your delivery service — don’t be shy about explaining exactly why ordering directly from your brand is best for the customer, the business, the delivery staff, and the community.

3. Build the strongest local SERP presence you can

Your ability to publish, distribute, and manage your non-website-based local assets will strongly contribute to your ability to compete in Google’s local search engine results. Depending on your market competition, you’ll need to meet and exceed your competitors’ investments in:

There’s no downplaying the hold corporate delivery websites have on Google’s SERPs, nor the fact that Google has special relationships with some of them that redound to Google’s own financial interests. In competitive markets, it will be no easy task to compete with these brands. Many local businesses may feel that “if you can’t beat them, join them” is the only option to remain operational.

But don’t overlook the powers you do have to compete by dint of running a beloved business and a brilliant search marketing strategy. You could even choose to utilize a third-party service only until you’ve got a large, built-in customer base you can guide to come directly to you for fulfillment in the years ahead.

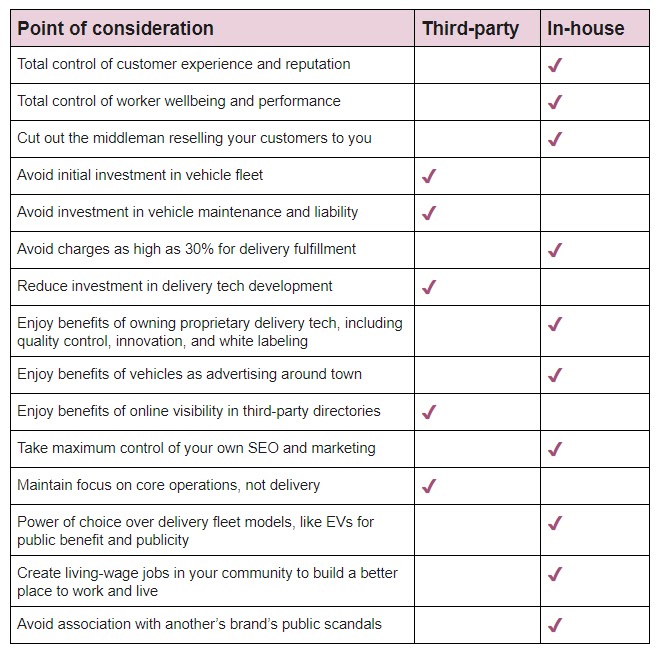

Summing up third-party vs. in-house delivery risks and benefits

As you evaluate which solution will be the best fit for last-mile operations for your brand, you’ll want to painstakingly chart out the pros and cons of each option. Here’s my simple checklist to get you started, delineating which solution is most likely to afford the benefits we’ve covered today, as well as a few extra points of consideration:

It’s too soon to predict what the sum total of change will be to the whole concept of delivery across all relevant industries. I talked with multiple business owners on St. Patrick’s Day, when California instituted its shelter-in-place order and all of them were hustling to create piecemeal solutions for remaining operational and serving my community. Several months later, brands are in a better position to evaluate consumer feedback and make adjustments to their delivery strategy.

As our risk/benefit chart shows, there are clear pros and cons for in-house vs. third-party implementation. Many brands will take a “best of both worlds” approach, like Just Salads, while hoping more customers come directly to them instead of their outsourcing partner. Other business owners may steer clear of the big delivery brands and bet on a smaller service, like Takeout Central serving North Carolina, or Lodel covering seven states in the American West. And definitely check out this CHOMP restaurant cooperative story over at Localogy.

What we can say with certainty in June of 2020 is that the brands you operate and market have major decisions to make about serving customers in both the best and worst of times. This is crucial work, and the only thing more important in local commerce right now is the significant power brands are suddenly wielding to set standards for how delivery and delivery persons will work. Recognize that power.

We’ve all had enough of experiencing the “worst”, and it’s motivation enough to plan a better future, with consistently excellent service for customers, the building blocks of lucrative reputation for brands, and local communities that deliver fair and dignified livelihoods for valued essential workers.

http://tracking.feedpress.it/link/9375/13644887