On Sunday afternoon, SpaceX will launch a crop of 64 small satellites from Southern California using a Falcon 9 rocket that the company has already flown twice before. It’s a groundbreaking launch for SpaceX in numerous ways. Not only is this the first time the company will fly a rocket for a third time, but this will be the largest batch of spacecraft that has ever taken off on a single flight from US soil.

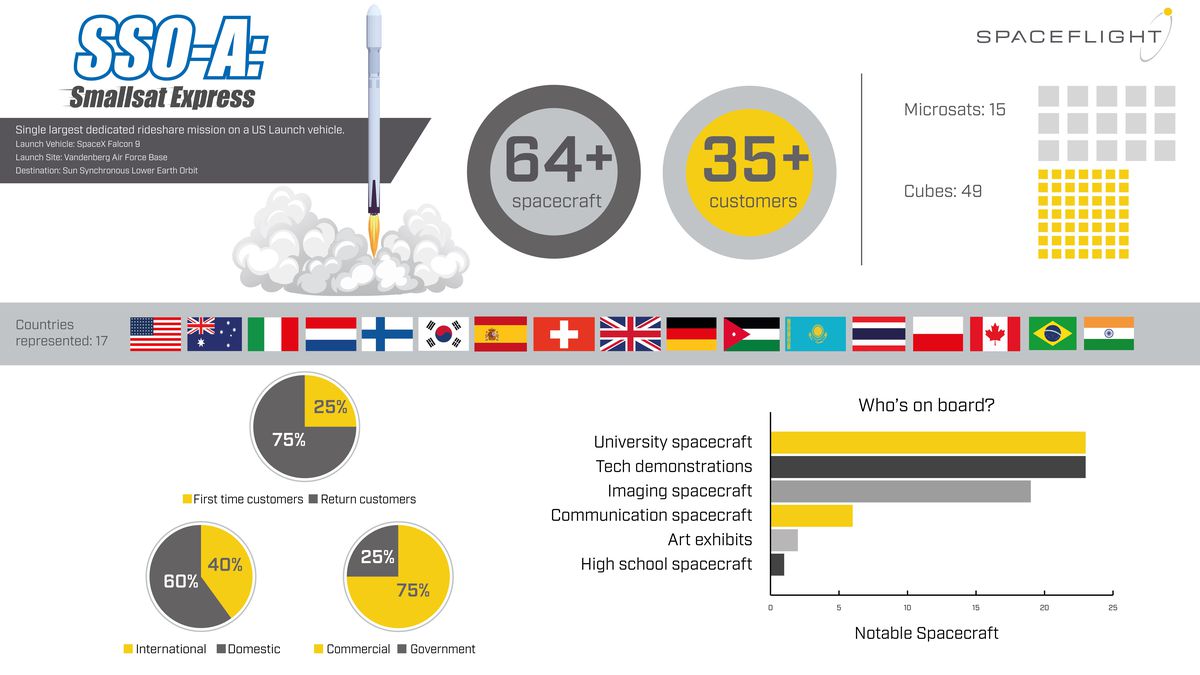

The massive ride-share was coordinated by Spaceflight Industries, a company that brokers rides on rockets for satellite operators. Typically, Spaceflight will help get small satellites into orbit by finding extra room on a vehicle that’s already launching a larger satellite to space. But this upcoming SpaceX launch, known as the SSO-A mission, is unique in that Spaceflight reserved the entirety of the Falcon 9 back in 2015. And since then, Spaceflight has been filling it up with small satellites from 35 companies, research organizations, schools, and artists from all over the world.

“Usually, we buy up excess capacity, and that’s how we fulfill the demand of our small satellite customers,” Curt Blake, CEO of Spaceflight’s launch services group, tells The Verge. “And basically we had to go to a model where we’re buying an entire launch vehicle in order to satisfy that demand.” Originally, 71 satellites were planned to fly, but a few of the operators weren’t ready in time leading up to the launch.

It’s not the first time a big crop of tiny satellites have all launched at once. In February 2017, an Indian PSLV rocket launched a record 104 satellites into orbit, and these huge ride-shares have become more common in recent years. But pulling off a mission of this kind is a big undertaking, requiring a lot of coordination with all of the operators involved. “The whole thing is super, super well-planned, as you can imagine,” says Blake. “Doing anything with that many different satellites and that many different procedures, to make sure it all comes together correctly — you really have to make sure you know when all the different pieces are coming together.”

At the heart of the Spaceflight mission is what is known as the payload stack, which is a large apparatus that houses all of the satellites during flight and then deploys them in space. The SSO-A stack stands at about 20 feet tall and is more than 10 feet wide. Spaceflight says it’s been working on this stack for about two years now, tailoring it to all of the customers’ needs. The main priority is that each satellite comes off the stack at the right time so that they reach their intended orbits and don’t run into each other in space. “It’s a lot of satellites that are all sequenced off in a way that we’ve done hundreds of simulations on, to make sure that there’s no recontact when we send all these different satellites out,” says Blake.

Some concerns have been raised about being able to track all these satellites once they’re deployed from the rocket. T.S. Kelso, manager of a satellite-tracking website called Celestrak, has argued that Spaceflight has not provided adequate information about the deployment sequence, which may make it hard to identify which satellite is which. However, Spaceflight says it has been working with The Combined Space Operations Center (CSpOC), which is responsible for tracking satellites for the US military. Over the last nine months, Spaceflight says it has coordinated with its customers and the CSpOC to provide data on the timing of each deployment.

“Spaceflight is a strong proponent of being stewards of space and operating responsibly,” a spokesperson for Spaceflight said in a statement. “We run countless simulations and tests to do everything we can to successfully place payloads on orbit. Once payloads have been deployed, it is the operator’s responsibility to make contact with and track the satellite.”

The payloads heading into orbit on this flight are all pretty unique. One satellite will look at the color of oceans to determine the health of the planet’s waters, while another will send algae into space to see what the space environment does to these organisms. Plus, there are a few art projects. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is sending up a 24-karat gold statue in honor of astronaut Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. Most notably, American artist Trevor Paglen will be launching his Orbital Reflector project — a satellite that will deploy a reflective balloon about the length of two school buses in space. The balloon will supposedly reflect sunlight, appearing as a bright point moving across the sky at night. It’s a project that hasn’t sat well with many astronomers, who are worried about too many bright objects mucking up their observations of the night sky.

As for the ride to space, SpaceX is using its most-used rocket yet. The company is enlisting a Falcon 9 rocket that flew for the first time in May and then a second time August. After each launch, the rocket landed on one of SpaceX’s drone ships in the ocean, enabling it to be flown to space again. This rocket will be the first one SpaceX has ever flown for a third time. It’s a feat made possible now that SpaceX is flying the final upgrade of its Falcon 9 fleet, what’s known as the Block 5. This version of the vehicle has been tailor-made for reusability, making it easier to land and then reuse the rocket once its mission is complete.

SpaceX plans to land the rocket again after this mission on another drone ship, so it’s possible this vehicle could fly for a fourth time. SpaceX CEO Elon Musk claims each Block 5 vehicle should be able to fly up to 10 times with minimal refurbishment needed between launches.

It’s taken a while to get the SSO-A mission off the ground, as SpaceX has had to reschedule it multiple times for weather and to run extra checks on the rocket. But finally, takeoff is slated for 1:31PM ET on Sunday, December 2nd, from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. SpaceX’s coverage of the event will start about 15 minutes prior to liftoff.

https://www.theverge.com/2018/12/1/18114894/spacex-falcon-9-reusability-sso-a-mission-rideshare-satellites