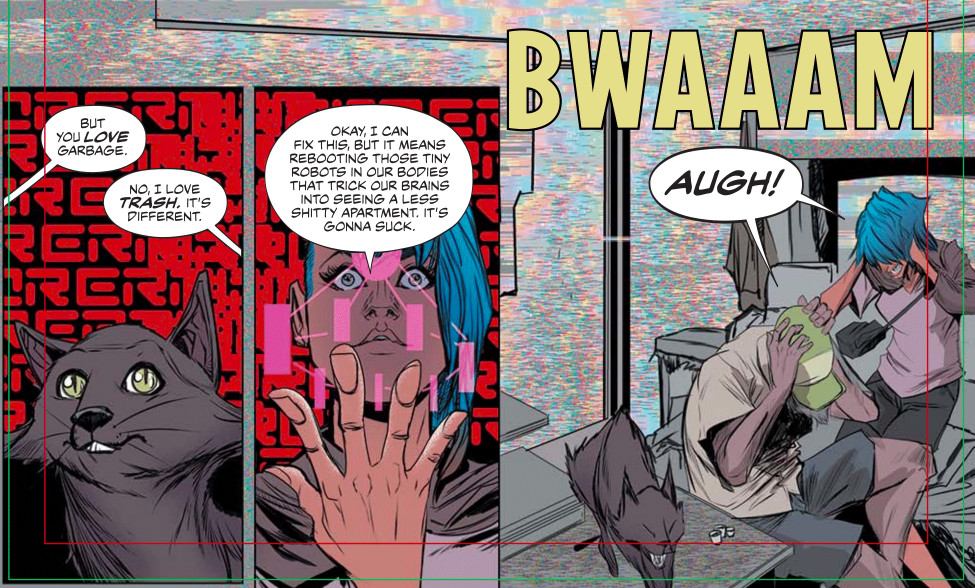

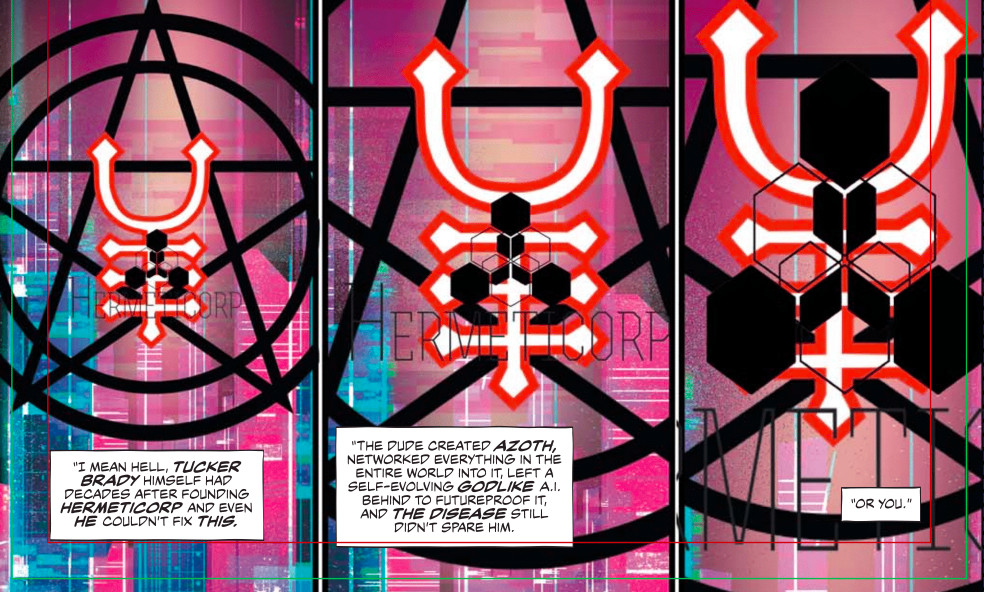

In the words of its writer, Hugo Award nominee Zoe Quinn, the Vertigo comic book Goddess Mode is a “weird neon baby of cyberpunk and magical girls,” a world where Arthur C. Clark’s first law reigns supreme, where any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. Our heroine is Cassandra Price, a brilliant mess of a human being eking out an existence at a megacorporation that her father’s work helped elevate into one of the most lucrative companies in the world.

She is a “code janitor,” a woman who deals in digital trash, desperately working to preserve the mediocre health care coverage that allows her father to stay alive despite the futuristic disease that has consigned him to a coma. “A lot of people need technology to survive,” says Quinn. “And if you’re renting it and you don’t own it or have control over it, you’re at the mercy of whoever does.”

All of that said, this is not a dystopia. “I don’t want to tell a story about how technological advancement is bad,” says Quinn. “I’m so tired of cyberpunk that says using machines to make your life better makes you less human. I think using technology to make your life better is probably the most human thing. We are the species that does that. To pretend that it is completely divorced from humanity is asinine to me, not least of all because of the collateral damage to disabled people.”

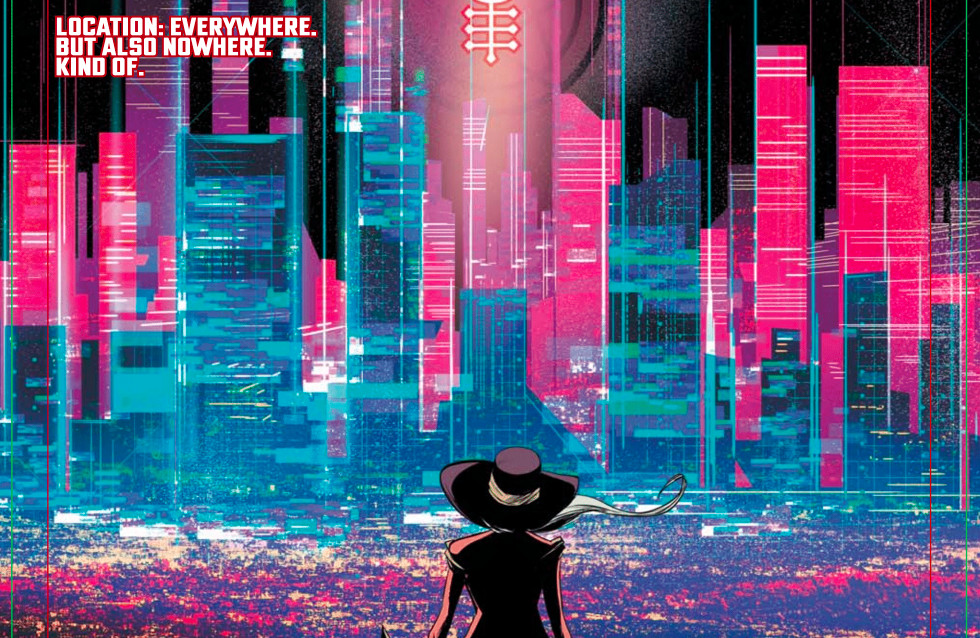

Tech is neither good nor bad in Goddess Mode: it simply is. It helps, it hurts, it exists in ways that accurately reflect the conflicted reality of systems and platforms and capitalism that we deal with in our own reality. “The story is really about how most things aren’t really inherently bad or good,” says Quinn. “It all depends on what we do with them. Whether it’s technology, having magic powers, having information — you can’t easily condense something into a binary, which is one of the reasons I’m using so many tech metaphors.” It is rendered, by Robbi Rodriguez and colorist Rico Renzi, in the fierce, retrofuturistic extremes of color and angle that defined the internet at its inception.

Despite the living death that her father endures, Psyche, the ubiquitous AI that Cassandra’s father created, is still very much alive, and widely deployed as a day-to-day task manager for the public at large that exists somewhere between Siri and Google. Psyche is always learning, but the most important lessons she learned were from a man who was singularly committed to ensuring that she learned the right ones. “Cassandra’s father was basically raising two girls at once,” says Quinn. “Her and the AI. He was working to humanize the machine and make it learn the right things from humans instead of the wrong things.”

This is no small task. If there is anything to take away from the extraordinarily problematic world of algorithmic decision making, it is how easily and gratefully we turn over our moral responsibilities to machines that we believe are more objective by merit of them trafficking in ones and zeros. We exist in a world where predictive policing, predictive sentencing, predictive loans and facial recognition have become the law of the land, without a moment of pause for the fact that all the data we feed into these systems and the programs we create to process them are as imperfect and biased as any other systems we could generate — regardless of the math.

“Everybody wants to think that if math did it, it’s perfect,” says Quinn. “But people are behind these algorithms and the data that’s being fed into them. So much of we see and hear consider to be true is dictated by algorithms that elevate what they think is the most important or valid to the forefront. And I think a lot of people don’t realize exactly how easily that can be manipulated… It always makes me super nervous how many tech companies don’t have data ethicists.”

Alchemical symbols abound in Goddess Mode, woven inextricably into code. Something is happening beneath the surface, something arcane and verging on the magical. The first issue veers towards a trope that has rarely been combined with tech: the often awkward and clumsy women who transform into impossibly beautiful and powerful heroines of the digital battleground. Which is to say, the magical girls of the 21st century. What if Sailor Moon lived inside the internet? Goddess Mode wants to know.

“I’ve been obsessed with magical girls forever,” says Quinn. “It’s the first time I saw queer girls in anything.” If you are unfamiliar with the trope, it goes a little bit like this: a young woman discovers a sort of power that she did not know she had, and she transforms, through an elaborate and elegant sequence into a sort of superheroine.

Quinn has a particular love of Sailor Moon, whose protagonist, Usagi, is best known for crying, whining, being late, and falling down a lot. She also saves the entire world in ways that that it would be incapable of defending against and entirely unprepared to comprehend. Again, the analogies are not abstruse. Sailor Moon is also, notably, supported by a group of other young women who must contend with similarly complicated but challenging notions of power and responsibility. This is a story about finding a way to exist in a world that does not entirely want you partly, if not largely, through the support of your friends.

“It’s a good allegory for what it’s like to end up connected to a bunch of people who are relative strangers, but who are dealing with the same crap as you that a lot of other people don’t understand, don’t think is even really happening,” says Quinn. “You’re trying to fight to make the world better, but it’s like trying to fix a car that’s crashing into you. I feel like magical girls are a really good allegory for that.”’

So are their powers based on technology, or magic? “Yes,” answers Quinn. “I mean, does it matter? At the end of the day it’s power. One of the reason I’m leaning so heavily into alchemy iconography and language is I really like the hermetic aspects that are kind of like scientific magic.”

Cassandra is a magician, a heroine, a tech genius, and a completely exhausted individual in a world that seems designed to work against her. She finds a way to become something better anyway, not because it’s easy but because it is the only way out of the economic, political and technological system that has wound its tendrils around her to the point of choking — something Quinn describes as a “gnarly rat king tangle of pain.” Goddess Mode is an answer written in neon and transformation sequences. “This is how you fight back,” says one character as she confronts a digital foe at a critical moment.

I ask Quinn what the elevator pitch is for Goddess Mode, shortly before our interview ends: “If you’re tired and exhausted and trying to fight for anything, really, and you just want to be encouraged to keep going, then this is me trying to subtweet you in a comic. Also, it’s real gay.”

https://www.theverge.com/2018/12/27/18157508/zoe-quinn-goddess-mode-comics-vertigo