Google ‘penny dreadful’ and you’ll see pages of results for the TV show of that name. The three-season gothic thriller, starring Eva Green no less, is set in late Victorian England. You might or might not know that the show takes its name from a new kind of serialized fiction which first appeared in London in the 1830s. It wasn’t Charles Dickens or Mary Shelley but it was cheap — only a penny — easy to read, entertaining, and extraordinarily popular.

Dreadful Readers

The emergence of the penny dreadful in England coincided with improved literacy. Nationwide educational reforms launched in the 1830s aimed to eventually provide universal, free, and compulsory state-funded education. In England, when printing was introduced in the 1470s, literacy was likely under 10%. By the 1830s, literacy rates were about 66% and 50% for men and women, respectively. By 1900 the literacy rate had risen to 97%. What’s more, in the nineteenth century there was sustained and unprecedented population growth. In England, between 1800 and 1850 the population doubled; it then doubled again between 1850 and 1900! That growth was accompanied by a marked demographic shift: already by the 1820s almost half of the UK’s population was under 20! Not only did the period mark an almost exponential increase in mass-produced and cheap print, on scales inconceivable prior to the Industrial Revolution, but it found a global mass market of readers — an increasingly large number of whom were young and literate. It’s in this environment that the penny dreadful made its debut.

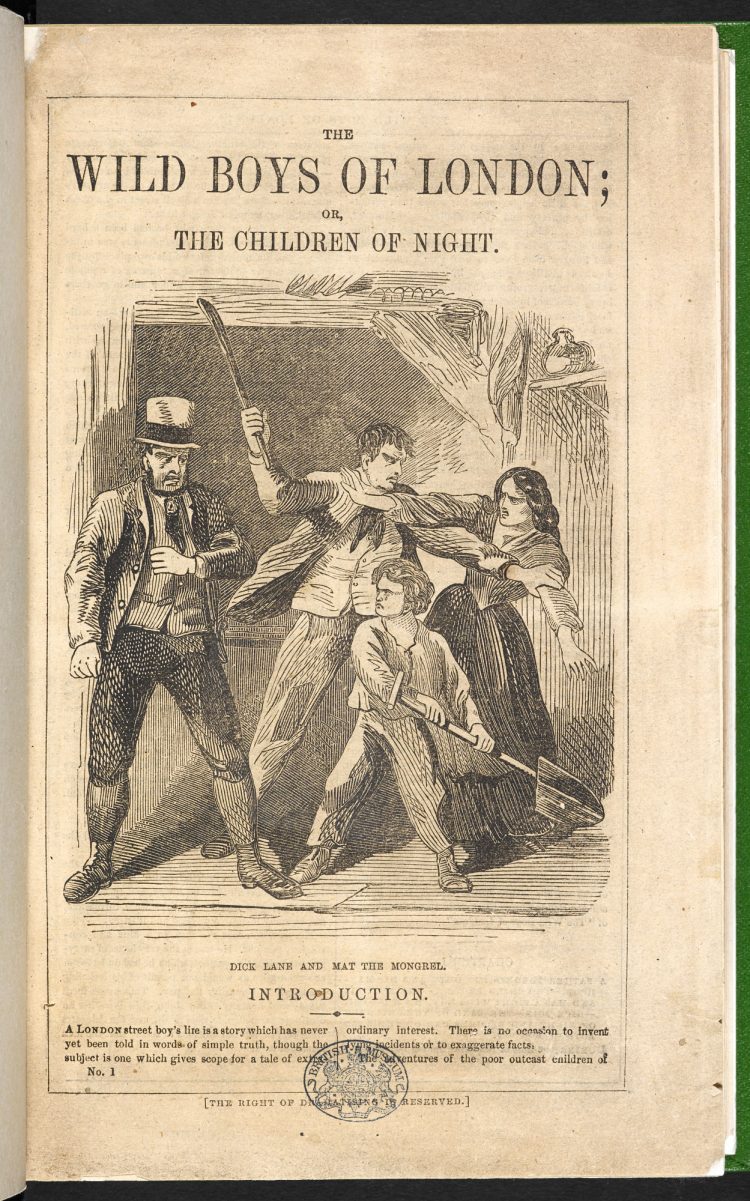

British Library

British LibraryBefore the nineteenth century, there wasn’t much in the way of fun and entertaining reading material for children. In fact, children’s literature as a genre was a pretty late starter, only getting off the ground in the eighteenth century, and even then it was usually didactic, pious, and moralizing — not particularly fun. The first children’s periodical, The Lilliputian Magazine, published by John Newbery, didn’t appear until 1751. By the late 1790s, Churches and religious organizations had begun to publish children’s periodicals and Sunday School magazines, but again they were rather stuffy and conservative, not really the kind of thing that children were excited to read. But that was about to change.

* The Cambridge Companion to English Literature, 1830–1914, p. 30

Binge Reading Victorian Netflix

In summing up the nineteenth-century ‘reading revolution’, historian Dr Mary Hammond writes: ‘The period 1830–1914 saw some of the greatest changes in readerships and the types and availability of reading material ever experienced in the Western world.’* By the start of that period, serialized fiction was already becoming hugely popular. It’s how Charles Dickens got his start with the serialization of The Pickwick Papers in 1836–37. But most early serialized fiction was intended for adult readers. What’s more, although books were now cheaper than they’d ever been, they were still beyond a working child’s meagre wages; for example, The Pickwick Papers was published in twenty 32-page installments, but at 5 shillings (1 shilling = 12 pennies) per installment, it was far too expensive for most working class adults, let alone children.

1

2

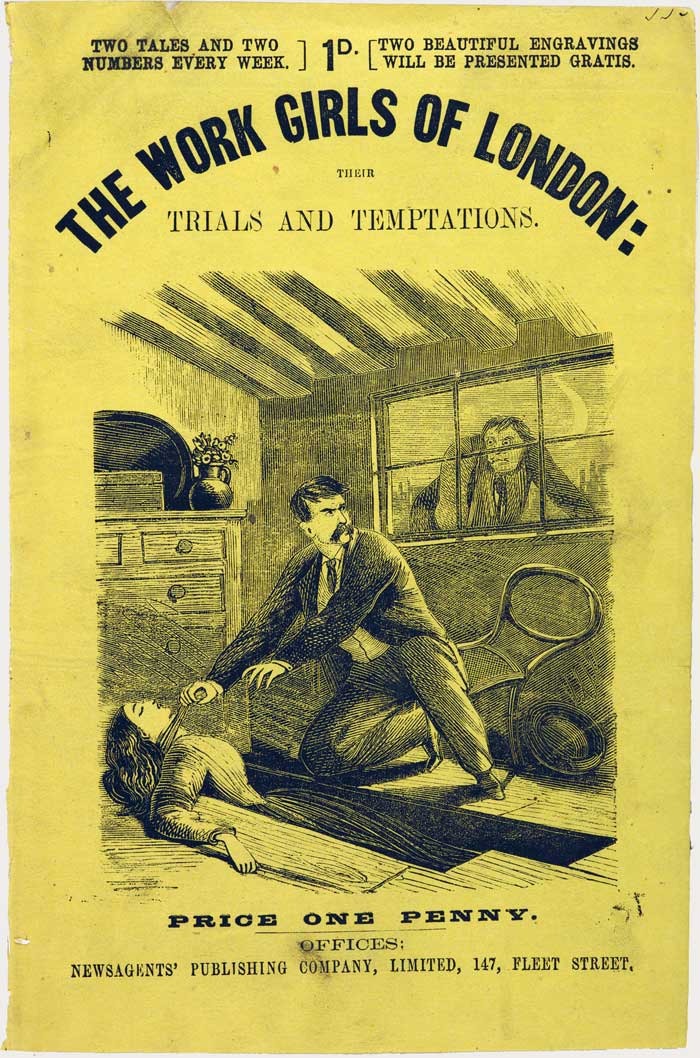

2. The Work Girls of London: their trials and temptations, 1865

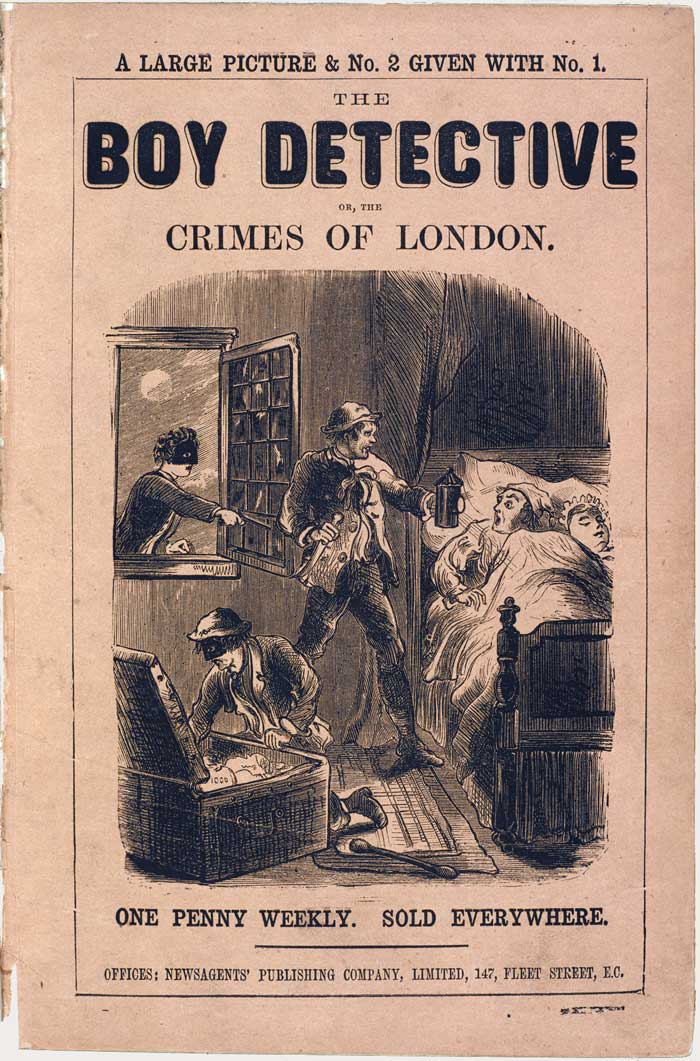

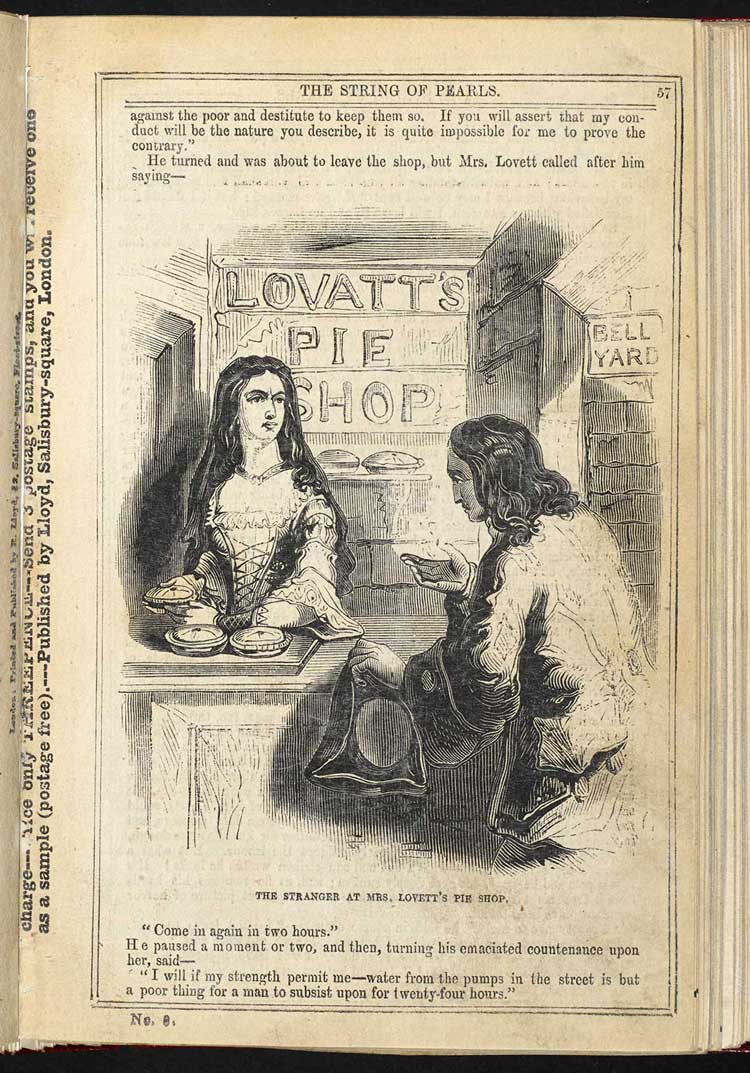

Enter the penny dreadful, typically eight or sixteen pages, printed on cheap paper, taking its serialized story cues from gothic thrillers of the previous century. Most of the stories are now forgotten, but one notable exception is everyone’s favorite homicidal barber, Sweeney Todd. Before he appeared in the pages of a book, he was butchering his victims and selling their remains as meat pies next door in a penny dreadful serial, ‘The String of Pearls: A Romance’, published in The People’s Periodical in 1846.

1

2

Dreadfully Deleterious

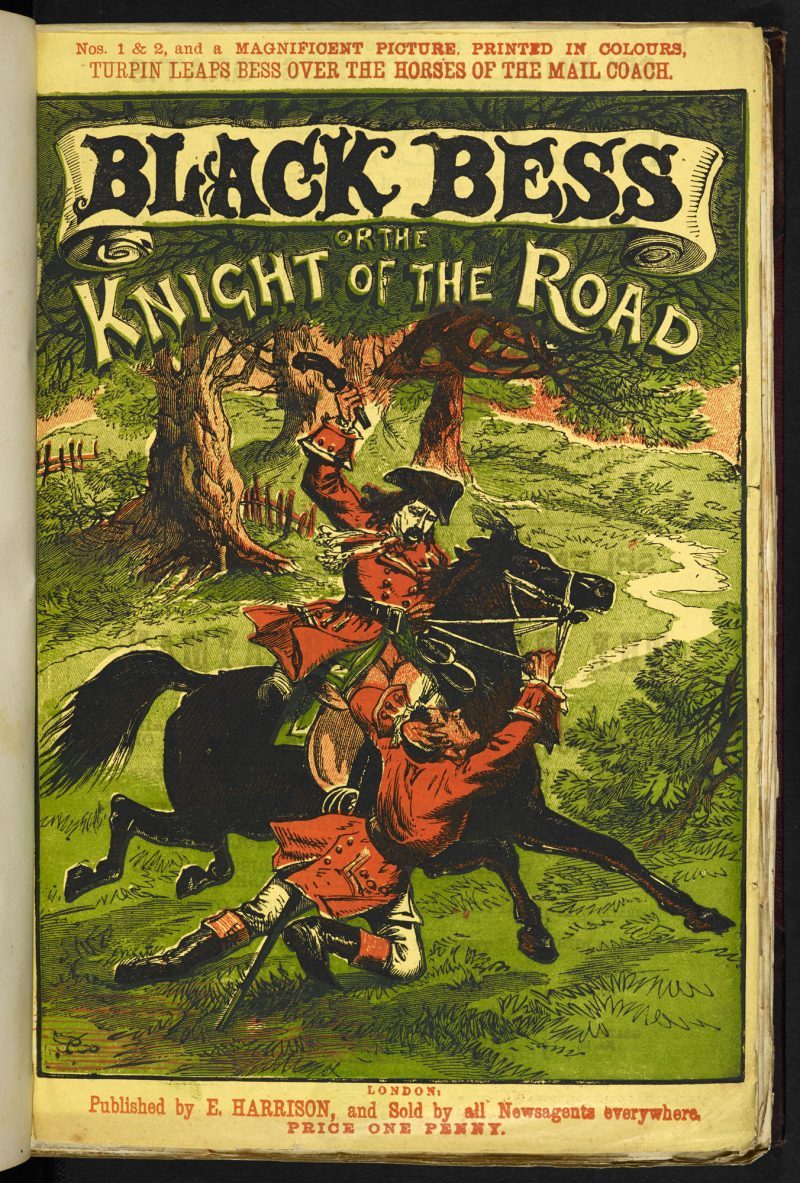

A nineteen-year-old house painter from rural Berkshire was arrested for robbery. Armed with a pistol, he had ambushed passersby presenting his victims with a Dick Turpin style ultimatum: ‘your money or I’ll blow your brains out!’ He then proceeded to steal their cash and watches. When apprehended he was wearing a mask and carrying a gun. In 1876, Alfred Saunders, an errand-boy in London, was arrested and charged with stealing seven pounds and four shillings (a considerable sum) from his father. He confessed to stealing the cash, and admitted using it to ‘breakfast and dine in rather an expensive way’. Thirteen-year-old Alfred, now with a taste for the high life, also purchased, with the stolen money, a toy gun, a lantern, and a cigar holder.*

* These two cases from Youth, Popular Culture and Moral Panics, 1998, pp. 80–85

What do these crimes have in common? Besides their youthful perpetrators and an apparent flair for the dramatic, it would appear very little. However, in both cases, the youths were found to be in possession of penny dreadfuls. And during both trials it was suggested that penny dreadfuls were responsible for turning these impressionable boys to crime.

1

2

2. Cover of the penny dreadful, Black Bess, c. 1866–68, a serialized fictional account of the real-life highwayman, Dick Turpin. Black Bess was the name of his horse

In Victorian England, especially in booming cities like London, crime was on the rise, especially juvenile crime. Not only were penny dreadfuls condemned as unsophisticated, or in the words of literary critic Francis Hitchman in 1890, ‘foul and filthy trash’, but they became a scapegoat. Long before radio, TV, cinema, video games, smart phones, and the Internet corrupted children [irony], quite a few Victorian cultural commentators blamed penny dreadfuls for corrupting impressionable young readers. In 1893, one complained:

It is almost a daily occurrence with magistrates to have before them boys who, having read a number of ‘dreadfuls’, followed the examples set forth in such publications, robbed their employers, bought revolvers with the proceeds, and finished by running away from home, and installing themselves in the back streets as ‘highwaymen’. This and many other evils the ‘penny dreadful’ is responsible for.*

* John Springhall, 1994, pp. 326–27

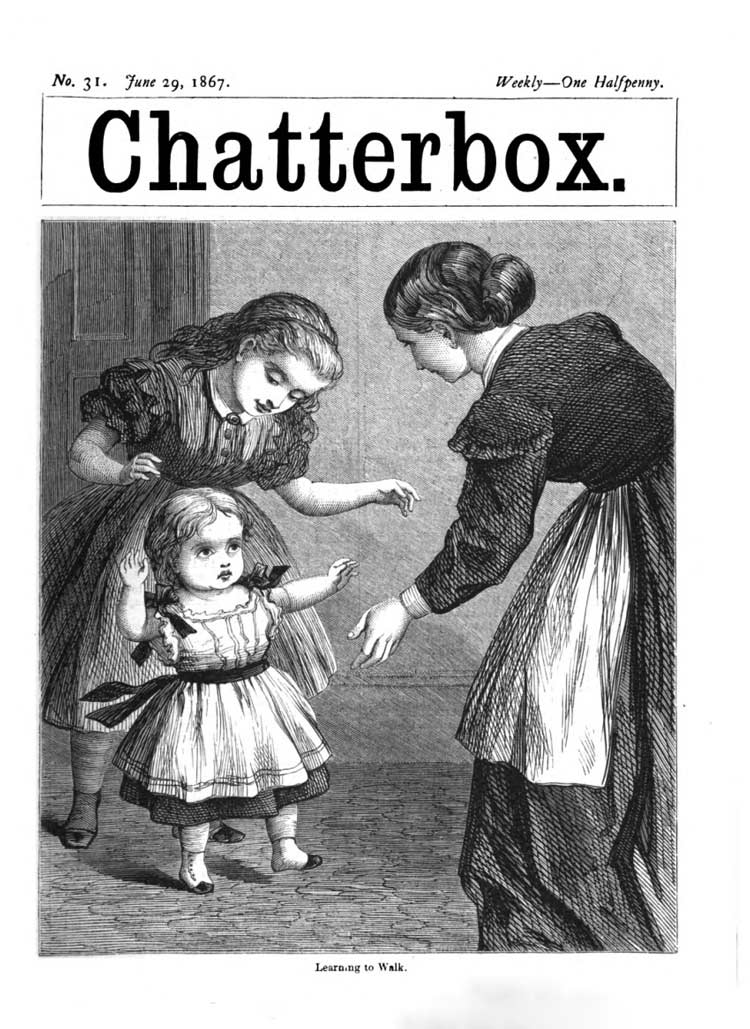

This fabricated moral panic induced pious publishers to launch rival periodicals intended to counteract the pernicious influence of penny dreadfuls. British Clergyman, John Erskine Clarke, launched such a periodical. His successful weekly Chatterbox (1866–1953), ran for decades. Out with blood and guts, pirates, bandits, highwaymen, and psychopaths; and in with tales of heroic dogs saving drowning children, saccharine morality tales, and kittens aplenty.

1

2

2. The weekly halfpenny Chatterbox was launched in 1866 to counteract the corrupting influence of the penny dreadful

Although Chatterbox sold for just half a penny, it’s very unlikely that it was regularly bought and read by working class children. Although penny dreadfuls were broadly condemned, not everyone agreed. Some saw penny dreadfuls as a gateway to more serious literature. Frederick Willis, a London hat-maker wrote that penny dreadfuls had ‘encouraged and developed a love of reading that led onwards and upwards on the fascinating path of literature’. And up-and-coming author H.G. Wells said of his boyhood love of penny dreadfuls, ‘Ripping stuff, stuff that anticipated Haggard and Stevenson, badly illustrated and very, very good for us’.

“It was Lord Northcliffe [Alfred Harmsworth] who killed the penny dreadful: by the simple process of producing a ha’penny dreadfuller.”▿

▿ A tongue-in-cheek A.A. Milne (author of Winnie the Pooh), 1948

* Penny dreadful & penny blood are commonly used synonymously. More precisely, ‘bloods’, from the c. 1830s, were for adult readers; ‘dreadfuls’, from the c. 1860s, were targeted primarily at children. See Gothic Fiction, from Shilling Shockers to Penny Bloods, pp. 140, 151

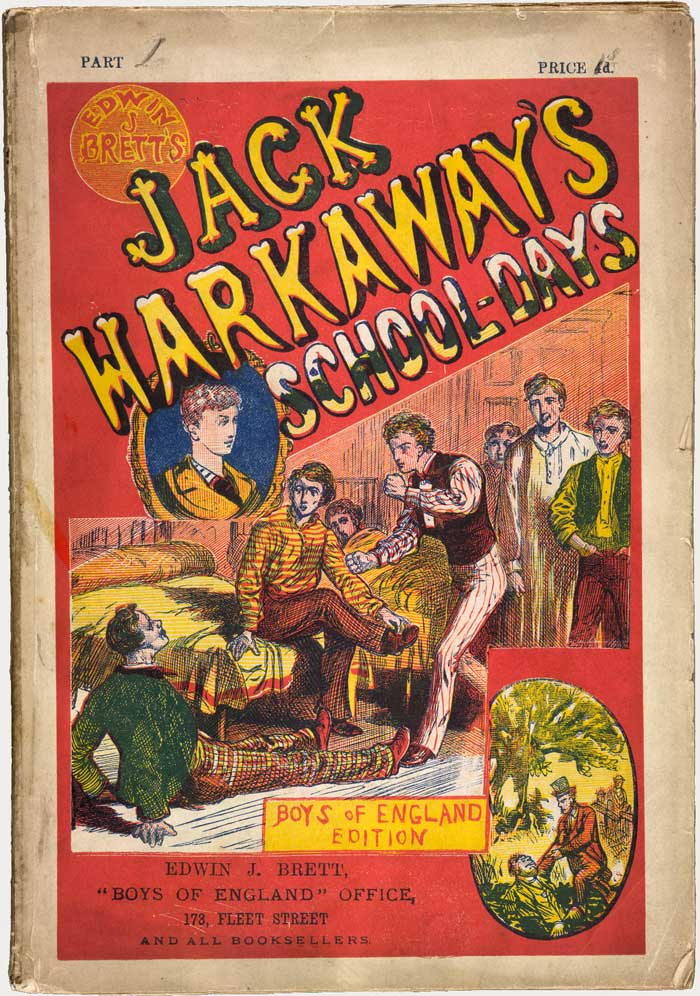

Between 1866 and 1914, in England, more than 500 children’s periodicals were published. In the early 1800s, penny dreadfuls* had been targeted at a broad working class audience. But that changed in the 1850s when publishers began to target children, especially young boys, with titles like Boy’s Own Magazine (1855–74), Boy’s Own Paper (1879–1967), Boy’s Journal (1863–71), Boys’ Miscellany (1863–64), The Boy’s Standard (1875–92), and the most popular Boys of England, debuting in 1866 with the gripping subtitle, ‘A Magazine of Sport, Sensation, Fun, and Instruction’. BOE was the most popular of the time, boasting a print-run of more than 250,000 by the late 1870s. Its founder Edwin Brett devised shrewd promotional campaigns to expand the magazine’s readership — they included competitions and prizes; among them were books, watches, dogs, pigeons, and ponies. The prize-draws regularly attracted more than 10,000 entries. The multi-pronged marketing strategy also included reader polls, standalone prints or posters, a Christmas special, and opportunities for its young readers to have their artwork or letters appear in the magazine.

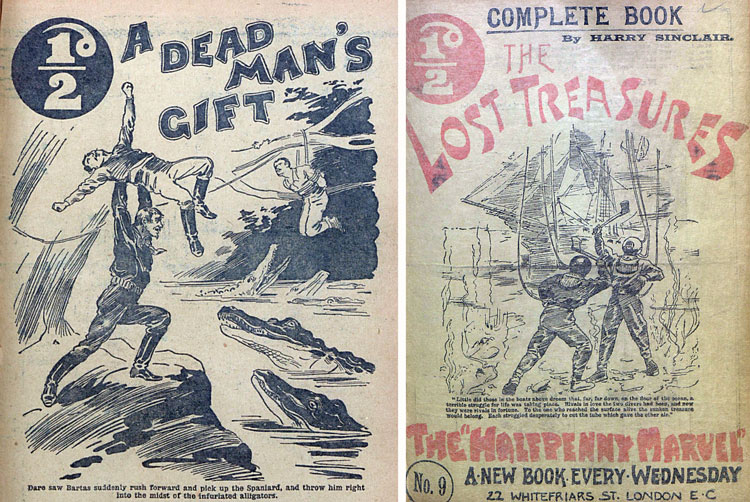

Curious storylines for a magazine claiming to take the moral high ground against violent & pernicious penny dreadfuls. The Halfpenny Marvel, 1895 & ’94Dr Bob Nicholson

Dreadful Decline

By the 1890s, the penny dreadful was competing with hundreds of periodicals and with more and cheaper books too. One of the first media moguls, the newspaper publisher Alfred Harmsworth, keen to combat the bad influence of penny dreadfuls (and make a pretty penny), launched several successful halfpenny magazines, beginning with The Halfpenny Marvel in 1893.

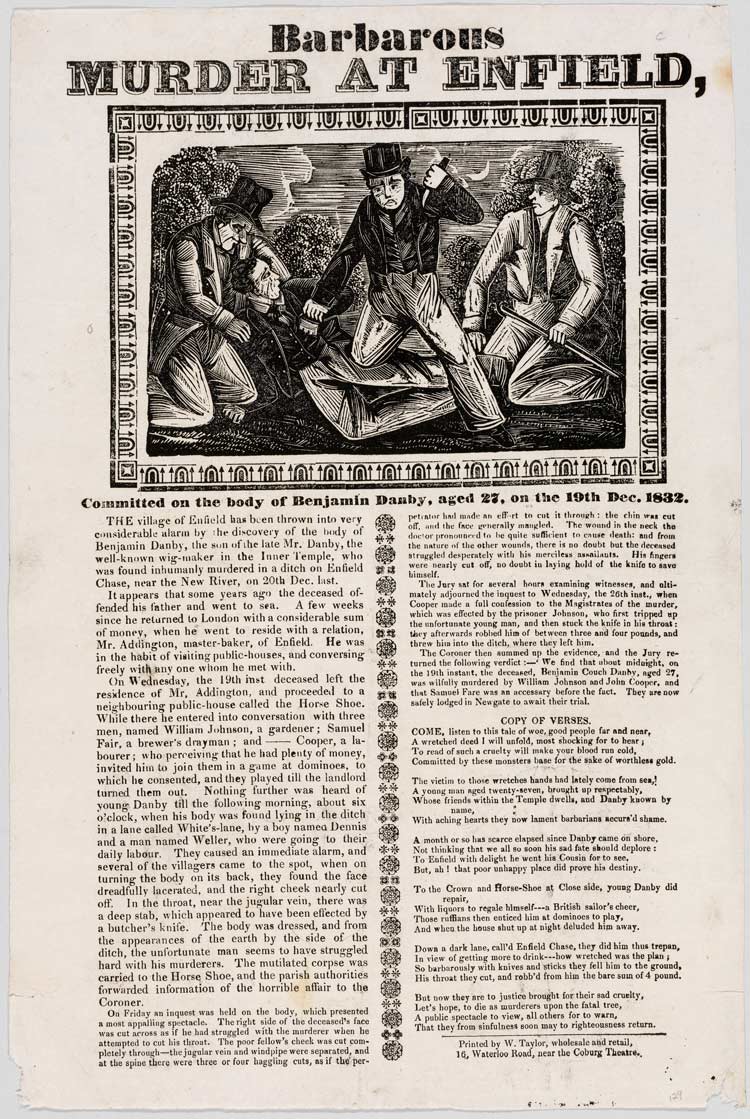

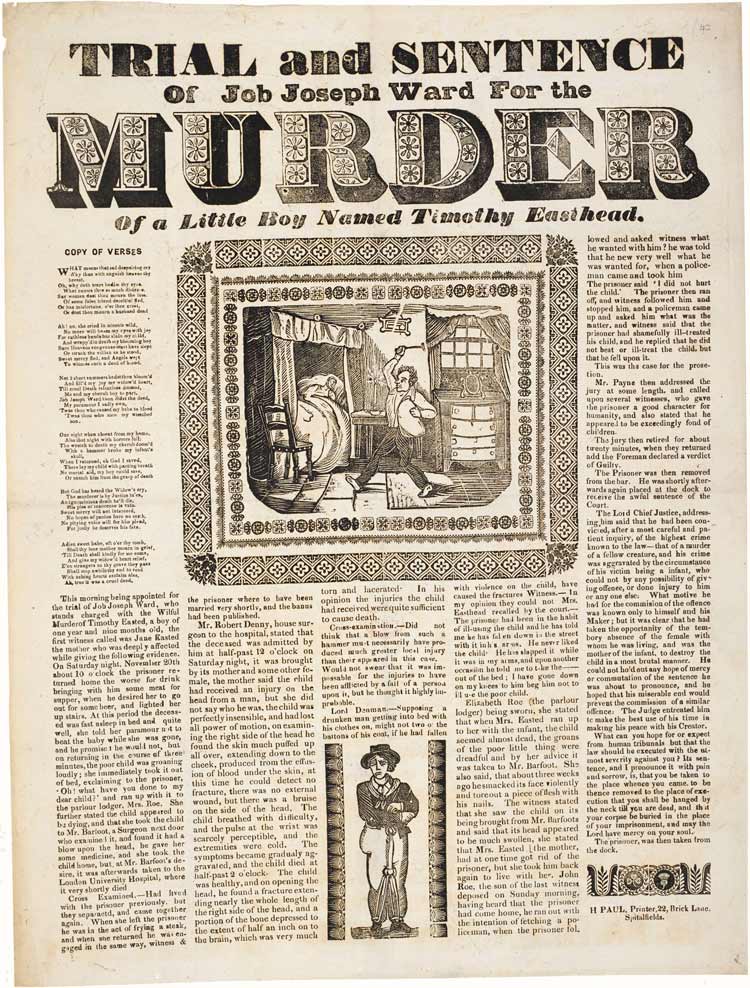

Murder Broadsides

* See Crime, Broadsides and Social Change, 1800–1850, p. 22

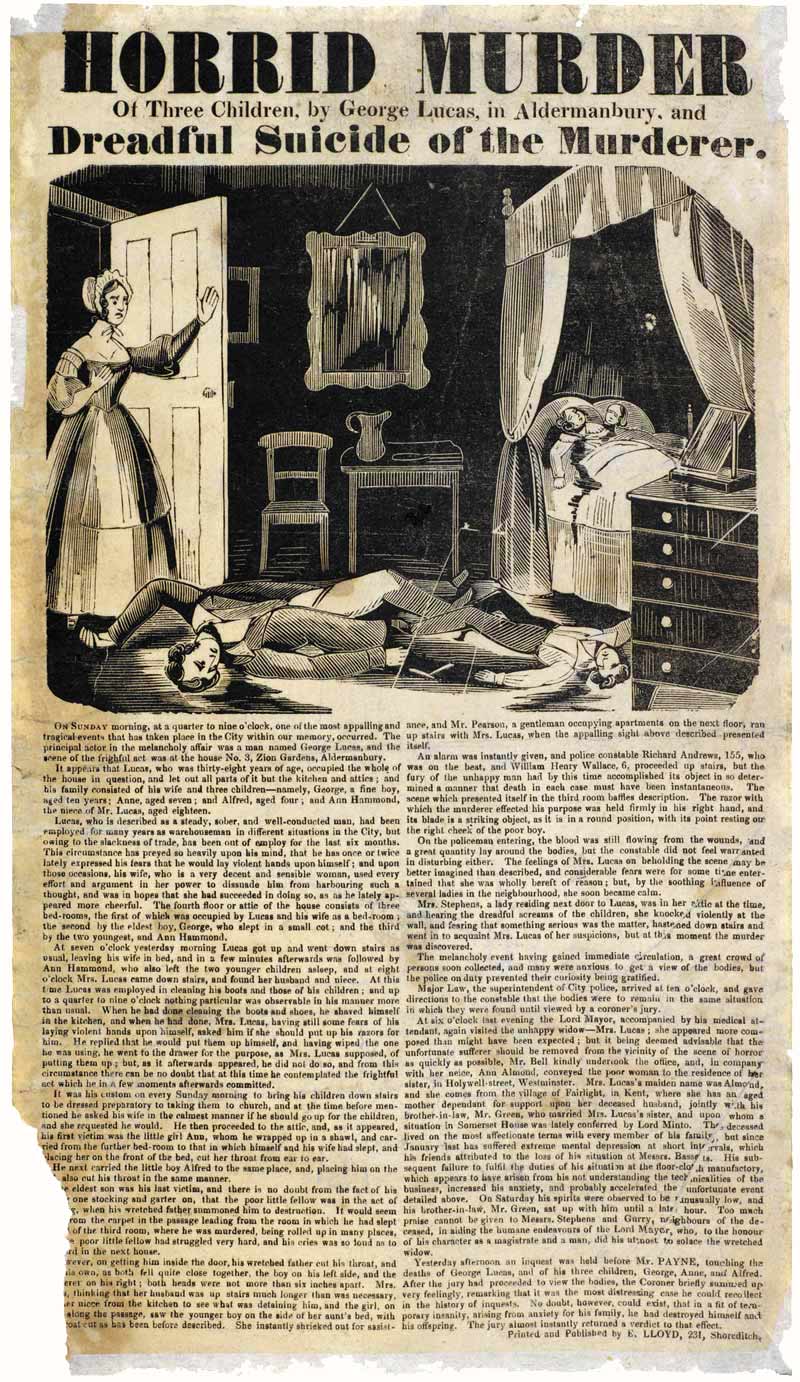

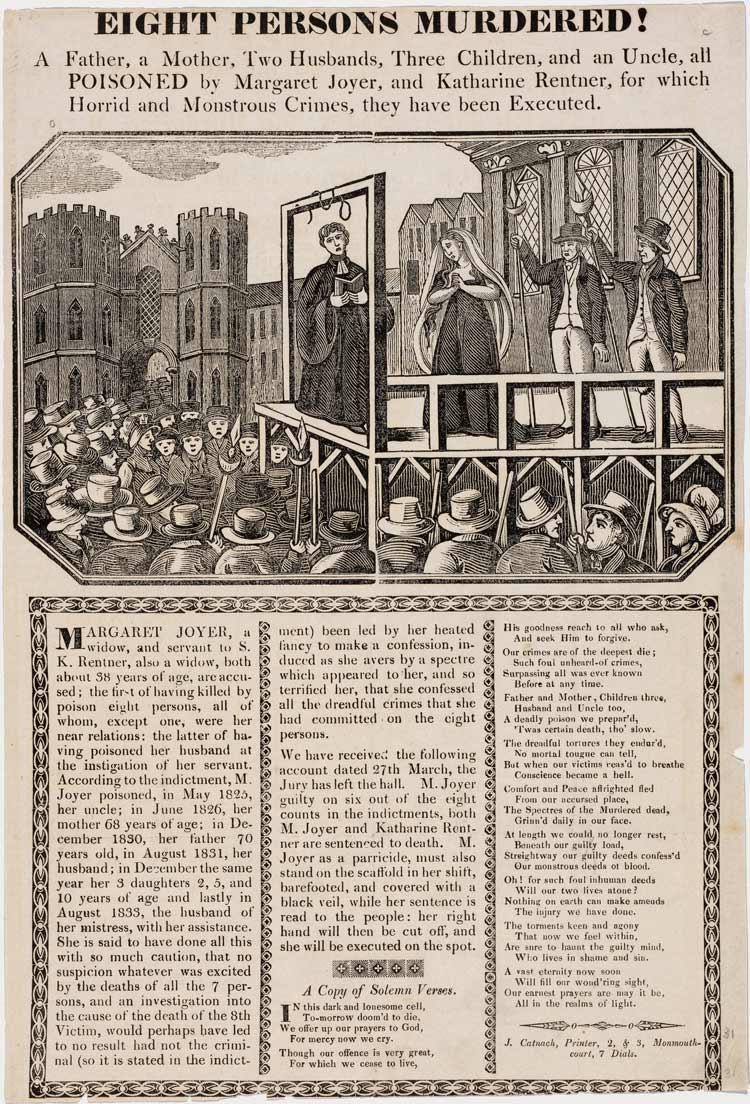

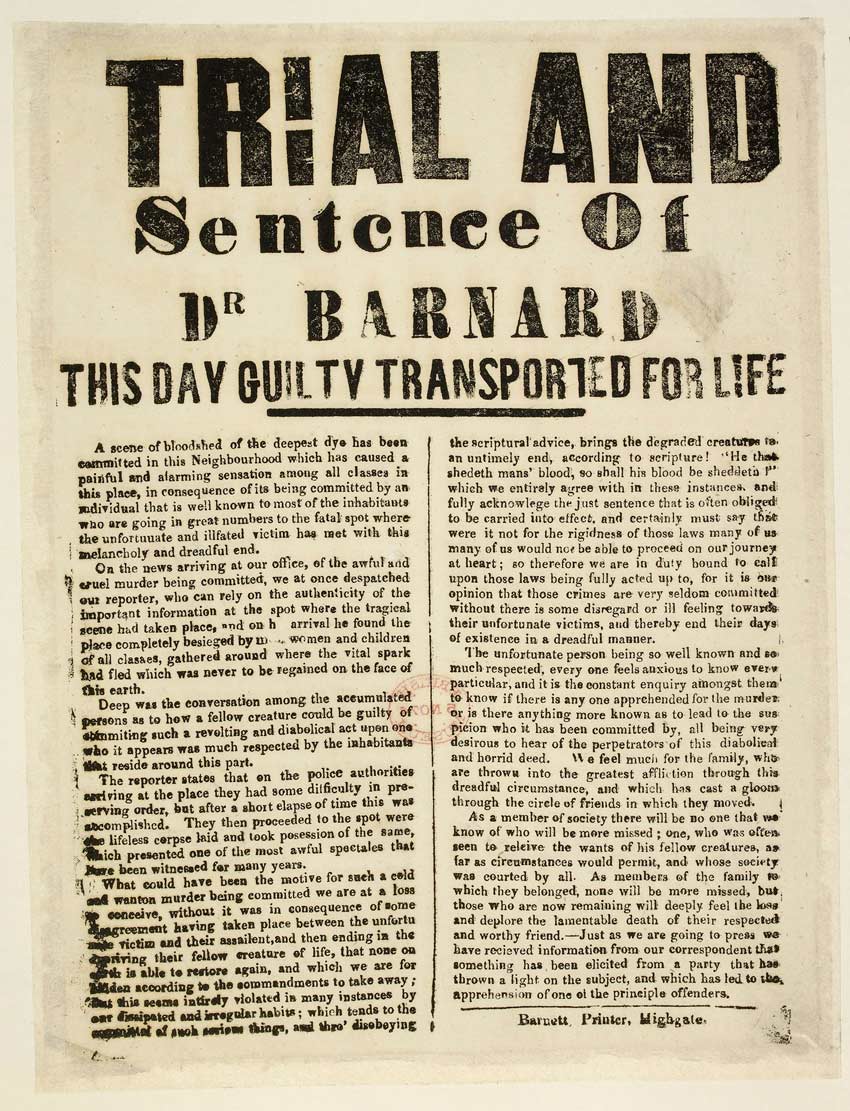

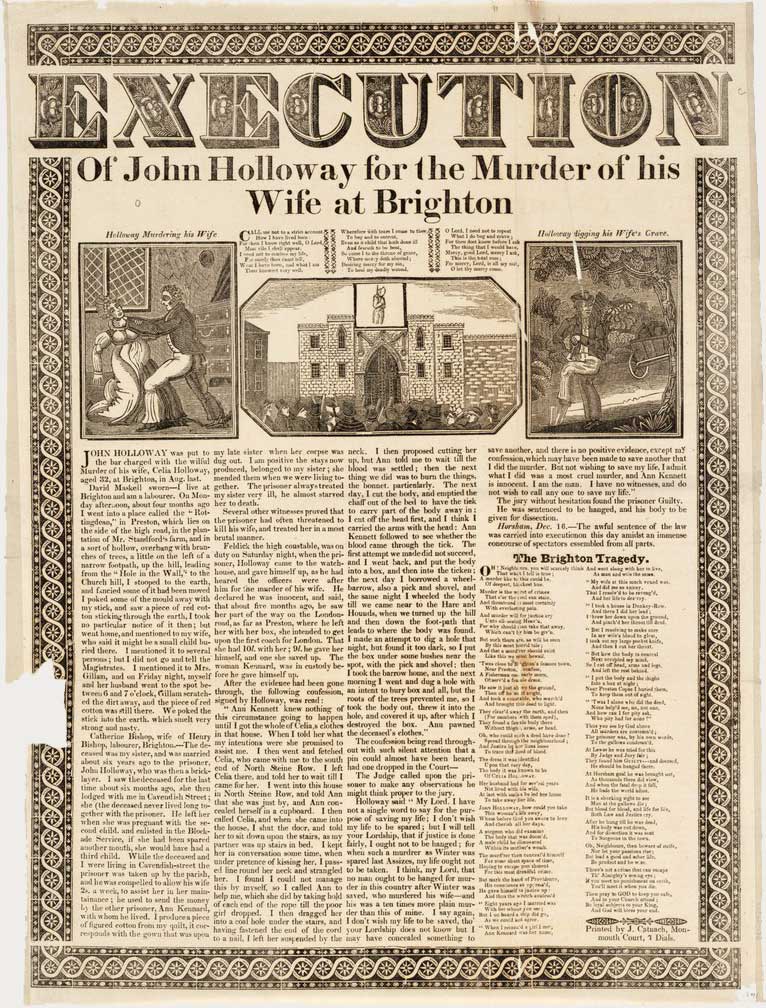

Executions had long been public affairs and were frequently attended by thousands, if not tens of thousands, with many coming from farther afield to ‘make a day of it’. The more notorious the condemned and the more grisly the crime, the greater the crowd. But executions were also an opportunity to make a profit. Sold on execution day, for a penny or less, were broadsides (sheets printed on one side) recounting the crimes and confessions of the condemned, and pity for their victims. They were accompanied by often lurid illustrations and gory details, including a little Victorian-style CSI to describe the perpetrators’ capture and conviction.

Left: A Souvenir ‘murder mug’, c. 1824 Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove; Right: Glazed earthenware figure of condemned murderer James B. Rush, 1848/49

Norfolk Museums Collections

Alongside the peddlers who sold broadsides were others hawking trinkets and souvenirs. While enjoying your fun family day out on execution day, you might treat yourself to a commemorative murder mug — yes, an actual mug commemorating someone’s execution by hanging. And if drinking your tea from a murder mug is not to your taste, perhaps I can interest you in a porcelain figure of James Rush, hanged in 1849 for a double murder, and whose execution drew a crowd of 20,000.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Harvard Library

Harvard LibraryMurder Fonts

Over the course of three centuries, from Gutenberg in the 1450s right through to John Baskerville in the middle of the eighteenth century, the technology of printing had remained virtually unchanged. In fact, so little had changed that Gutenberg would surely have felt quite at home in a printshop of the 1750s. But the Industrial Revolution changed every aspect of the printing industry, powering it with steam and then electricity, mechanizing printing, typefounding, paper-making and typesetting, transforming printing into a genuine mass medium. But the nineteenth century also witnessed a rich aesthetic transformation too — a full-blown typographic renaissance. If in the eighteenth century Giambattista Bodoni had shocked his contemporaries with the extreme contrast and novelty of his fonts, then the nineteenth century shrugged and said, ‘hold my beer’.

Murder broadsides made use of a dizzying array of new display typefaces designed for a burgeoning poster advertising industry. The so-called Fat Face typefaces, extreme contrast versions of the previous century’s Didone or Modern types, were especially popular with printers of these broadsides.

The century also gave birth to the first sans serif printing types, c. 1816, initially called Egyptian and later dubbed Grotesque or Gothic. The 1820s saw the first reversed contrast typefaces, initially called French Antique or Italian. Then Ionic, which shared a lot with Moderns and Egyptians but with bracketed serifs. Then came the slab serifs (confusingly, like the first sans, also know as Egyptian) appeared in the same decade, immortalized in cuts like Clarendon (1845). And then there was everything in between: condensed, expanded, shaded, inline and outline, flared, twisted, rounded, wedge and bifurcated serifs, ornamented, floral, and other eccentricities which still pretty much defy classification.

British Library

British Library

Harvard Library

Harvard Library

Harvard Library

Harvard Library

Harvard Library

Harvard Library

Harvard Library

Harvard Library

Harvard Library

Harvard LibraryMurder or execution broadsides followed a fairly consistent formula: Fat face, bold condensed sans and heavy Clarendon-esque slab serifs for the title and subtitles, and Sometimes even a decorative wood type — I guess the printer, who had surely purchased the expensive wood-type for other purposes, wished to get their money’s worth.

Cut & paste hangman. The same Old Bailey courthouse woodcut with space left under the scaffold for the addition of the requisite number of hanging figures. The courthouse has since been rebuilt (1902), but in the background is St Sepulchre’s Church, built in the 17th century and still standing Harvard Library

The wood engravings and woodcuts used for the illustrations are of the victim, the actual crime in progress, or a town-square filled with spectators. Many of the illustrations are of executions performed outside the Old Bailey in London, which was once attached to Newgate prison. Frequently in the gallows woodcuts, a space is left under the scaffold for the addition of the requisite number of hanged figures.

“Between 1735 and 1868 in England and Wales, more than 9,300 people convicted of capital crimes were publicly executed.”▿

▿Source: Harvard Library

The End

In England, the Capital Punishment Amendment Act of 1868 brought an end to public executions and the murder broadside. And by the start of the twentieth century, penny dreadfuls were on the way out, steadily supplanted by countless alternatives and sometimes evolving into new kinds of periodicals, from comics to general interest and educational magazines; but also into equally lurid and sensational periodicals like the popular, The Illustrated Police News, forerunner of the tabloid press, and once voted, ‘the worst newspaper in England’.

It ran sensational stories of blood, guts, and the bizarre — everything from a maniacal octopus to suicides, murders, murder-suicides, peeping-toms, patricide, matricide, and fratricide; and with truly memorable headlines like, ‘Shock for mourners when dead girl sits up in coffin’ (22 April 1899), and ‘Girl shoots a man dead at a ball for treading on her foot and declining to apologize’ (5 Feb. 1898).

The nineteenth century witnessed a reading revolution. Never before in the West had so many read so much. Crime broadsides shed light on early nineteenth-century mores, on attitudes towards morality, crime, punishment and redemption — and their penchant for the macabre. Although cheap, sensational, and ephemeral, penny dreadfuls were always much more than disposable entertainment. They improved literacy, and whether praised or pilloried, they got children excited about reading regularly. The genre forever transformed children’s literature, introducing generations of young readers to the novel and enduring notion of reading for pleasure. ◉

ILT is made possible by the generous sponsorship of Positype, & the support of these friends.